-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 768

File System, Part 7: Scalable and Reliable Filesystems

Most filesystems cache significant amounts of disk data in physical memory. Linux, in this respect, is particularly extreme: All unused memory is used as a giant disk cache.

The disk cache can have significant impact on overall system performance because disk I/O is slow. This is especially true for random access requests on spinning disks where the disk read-write latency is dominated by the seek time required to move the read-write disk head to the correct position.

For efficiency, the kernel caches recently used disk blocks. For writing we have to choose a trade-off between performance and reliability: Disk writes can also be cached ("Write-back cache") where modified disk blocks are stored in memory until evicted. Alternatively a 'write-through cache' policy can be employed where disk writes are sent immediately to the disk. The latter is safer (as filesystem modifications are quickly stored to persistent media) but slower than a write-back cache; If writes are cached then they can be delayed and efficiently scheduled based on the physical position of each disk block.

Note this is a simplified description because solid state drives (SSDs) can be used as a secondary write-back cache.

Both solid state disks (SSD) and spinning disks have improved performance when reading or writing sequential data. Thus operating system can often use a read-ahead strategy to amortize the read-request costs (e.g. time cost for a spinning disk) and request several contiguous disk blocks per request. By issuing an I/O request for the next disk block before the user application requires the next disk block, the apparent disk I/O latency can be reduced.

My data is important! Can I force the disk writes to be saved to the physical media and wait for it to complete?

Yes (almost). Call sync to request that a filesystem changes be written (flushed) to disk.

However, not all operating systems honor this request and even if the data is evicted from the kernel buffers the disk firmware use an internal on-disk cache or may not yet have finished changing the physical media.

Note you can also request that all changes associated with a particular file descriptor are flushed to disk using fsync(int fd)

Don't worry most modern file systems do something called journalling that work around this. What the file system does is before it completes a potentially expensive operation, is that it writes what it is going to do down in a journal. In the case of a crash or failure, one can step through the journal and see which files are corrupt and fix them. This is a way to salvage hard disks in cases there is critical data and there is no apparent backup.

Disk failures are measured using "Mean-Time-Failure". For large arrays, the mean failure time can be surprisingly short. For example if the MTTF(single disk) = 30,000 hours, then the MTTF(100 disks)= 30000/100=300 hours ie about 12 days!

Easy! Store the data twice! This is the main principle of a "RAID-1" disk array. RAID is short for redundant array of inexpensive disks. By duplicating the writes to a disk with writes to another (backup disk) there are exactly two copies of the data. If one disk fails, the other disk serves as the only copy until it can be re-cloned. Reading data is faster (since data can be requested from either disk) but writes are potentially twice as slow (now two write commands need to be issued for every disk block write) and, compared to using a single disk, the cost of storage per byte has doubled.

Another common RAID scheme is RAID-0, meaning that a file could be split up amoung two disks, but if any one of the disks fail then the files are irrecoverable. This has the benefit of halving write times because one part of the file could be writing to hard disk one and another part to hard disk two.

It is also common to combine these systems. If you have a lot of hard disks, consider RAID-10. This is where you have two systems of RAID-1, but the systems are hooked up in RAID-0 to each other. This means you would get roughly the same speed from the slowdowns but now any one disk can fail and you can recover that disk. (If two disks from opposing raid partitions fail there is a chance that recover can happen though we don't could on it most of the time).

RAID-3 uses parity codes instead of mirroring the data. For each N-bits written we will write one extra bit, the 'Parity bit' that ensures the total number of 1s written is even. The parity bit is written to an additional disk. If any one disk (including the parity disk) is lost, then its contents can still be computed using the contents of the other disks.

One disadvantage of RAID-3 is that whenever a disk block is written, the parity block will always be written too. This means that there is effectively a bottleneck in a separate disk. In practice, this is more likely to cause a failure because one disk is being used 100% of the time and once that disk fails then the other disks are more prone to failure.

A single disk failure will not result in data loss (because there is sufficient data to rebuild the array from the remaining disks). Data-loss will occur when a two disks are unusable because there is no longer sufficient data to rebuild the array. We can calculate the probability of a two disk failure based on the repair time which includes not just the time to insert a new disk but the time required to rebuild the entire contents of the array.

MTTF = mean time to failure

MTTR = mean time to repair

N = number of original disks

p = MTTR / (MTTF-one-disk / (N-1))

Using typical numbers (MTTR=1day, MTTF=1000days, N-1 = 9,, p=0.009

There is a 1% chance that another drive will fail during the rebuild process (at that point you had better hope you still have an accessible backup of your original data.

In practice the probability of a second failure during the repair process is likely higher because rebuilding the array is I/O-intensive (and on top of normal I/O request activity). This higher I/O load will also stress the disk array

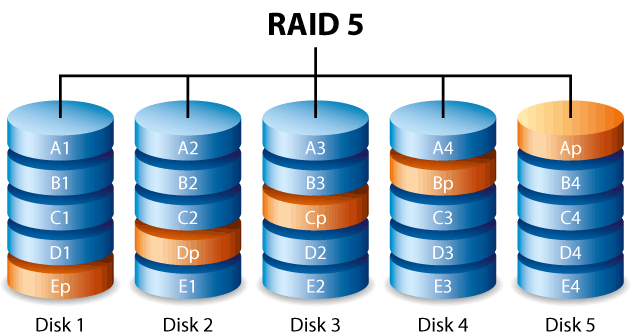

RAID-5 is similar to RAID-3 except that the check block (parity information) is assigned to different disks for different blocks. The check-block is 'rotated' through the disk array. RAID-5 provides better read and write performance than RAID-3 because there is no longer the bottleneck of the single parity disk. The one drawback is that you need more disks to have this setup and there are more complicated algorithms need to be used

Failure is the common case Google reports 2-10% of disks fail per year Now multiply that by 60,000+ disks in a single warehouse... Must survive failure of not just a disk, but a rack of servers or a whole data center

Solutions:

- Simple redundancy (2 or 3 copies of each file) e.g., Google GFS (2001)

- More efficient redundancy (analogous to RAID 3++) e.g., Google Colossus filesystem (~2010)

- customizable replication including Reed-Solomon codes with 1.5x redundancy

Legal and Licensing information: Unless otherwise specified, submitted content to the wiki must be original work (including text, java code, and media) and you provide this material under a Creative Commons License. If you are not the copyright holder, please give proper attribution and credit to existing content and ensure that you have license to include the materials.