- Scala Cheatsheet

- Twitter Scala School

- Scala website

- Alternatively, Functional Programming in Scala by Paul Chiusano and Rúnar Bjarnason is a great alternative/complement to taking this course.

- Get practice with Scala by solving the 99 Scala problems and the problems of Project Euler and Scala Exercises.

- Notes and Cribsheet from iirvine

Week 1 -

-

Evaluation strategy and recursion: fixedpoint.sc demonstrates writing a basic function in scala. eval_strategy.sc illustrates call-by-vale (imperative, C) versus call-by-name (not to be confused with lazy evaluation).

def constOne(x: Int, y: => Int) = 1 //y has a type '=> Int' which means y is passed as a by-name parameter constOne(1+2, loop) //reduces to 1 constOne(loop, 1+2) //infinite cycle

Week 2 -

-

higher order functions - basically functions that has functions as arguments. See HOF.sc for some examples.

-

Currying and Partial applications - currying is the process of transforming a function that takes multiple arguments into a function that takes a single argument and returns another function that returns another function that takes remaining arguments. This way, we can transform any function of multiple arguments into chain of multiple functions with single argument (e.g., a partially applied function). Why would we want to break up a big complicated function that takes a dozen arguments into many smaller functions that take a few arguments each?

// without curry def fun(z: Int, x: Int): Int = z + x //fun is a function that takes two arguments List(1,2,3) map (x => fun(5, x)) List(1,2,3) map (fun(5, _)) // with curry def fun2(z: Int)(x: Int): Int = z + x List(1,2,3) map fun2(5) //fun2(5), the argument of map, is a partially applied function of type Int => Int

-

Scala class and datastructure in scala example: Rational.scala, which gets called in datastructure.sc

Week 3 -

-

To run a Scala Application, just add a main function:

object ScalaProgram { def main(args: Array[String]) = { println("hello world!") } }

-

class hierarchy and organization. See example: List.scala and IntSet.scala, which is called by class_hierarchy.sc.

trait Tree[+T] case class Leaf[T](value: T) extends Tree[T] case class Branch[T](left: Tree[T], right: Tree[T]) extends Tree[T] case object Empty extends Tree[Nothing] object Tree { //companion object //functions in here can pattern match on case Leaf, case Branch, or case Empty. }

-

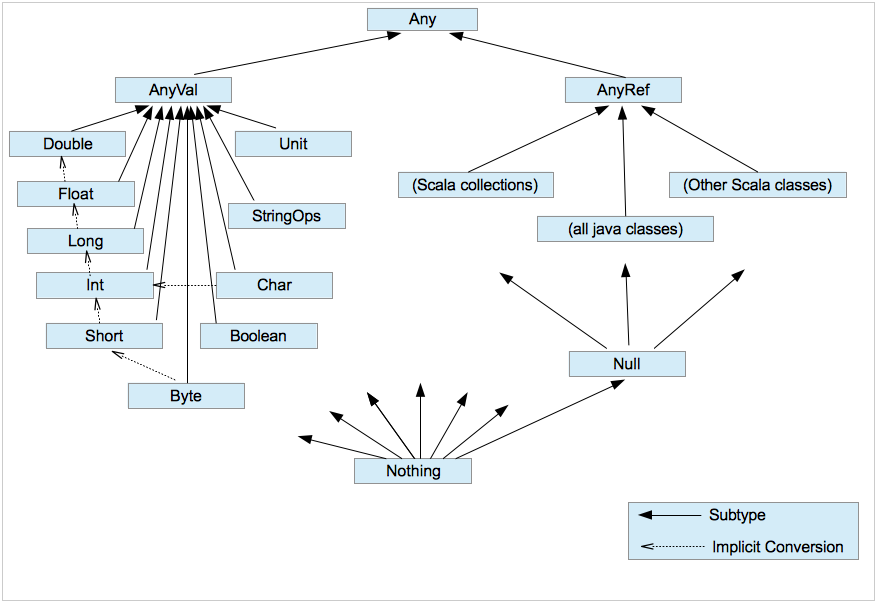

Scala traits and abstract class. See classes_org.sc for examples of extending traits as well as when you use Nothing and AnyVal.

Week 4 -

-

Subtyping and typing rules for functions: see subtyping.sc. Functions are contravariant in their argument types and covariant in their result type. For example, the scala Function1 trait:

/* Variance * the '-' and '+' in front of the type A and R denotes the * variance. '+R' and '-A' means A <: R or 'A is a subtype of R' or * 'R is a supertype of A' */ trait Function1[-A, +R] { def apply(x: A): R }

-

polymorphism, illustrated in MyList.scala and the scala worksheet. collectionlist.sc. As another example, Boolean2.scala implements a boolean using an abstract class and two companion objects. In the object oriented approach with a trait and class implementations, we can make a singleton for things that only has one implementation. See the Scala implementation of the Peano number in Nat.scala.

-

Pattern Matching, or a fancy if statements (a generalization of switch from C/Java to class hierarchies) is a good solution for Functional Decomposition. As the purpose of decomposition is to reverse the construction process, pattern matching offers a great way to automate this deconstruction process. The comparison of pattern matching decomposition approach (using scala trait and case class) with the object oriented approach (trait and class implementations) is highlighted in Expr.scala, Expr2.scala, and Expr3.scala.

Week 5 -

-

List operations - functions on list processing

-

Pairs and Tuples - can help with program composition and decomposition. Pair is a 2-tuple. Pair can only take two things. Tuples can take as long of a sequence as you want.

//pair val pair = ("answer", 42) //tuple //value assign using pattern matching - preferred because it's shorter and clearer val (label, value1, value2) = (pair._1, pair._2, 80) pair._1 //equivalent to label: "answer" pair._2 //equivalent to value1: 42

-

Implicit Parameters and

scala.math.Ordering -

Higher Order List Functions (HOFs)

-

HOFs that take unary operators:

filter,filterNotandpartition(combination filter and filterNot.takeWhile,dropWhileandspan(combibnation takeWhile and dropWhile) -

HOFs that take binary operators:

reduceandfold//Scan is like recording the intermediate values of computing a fold //fold List("a","b","c").fold("!")((x,y) => x+y) // !abc List("a","b","c").scan("!")((x,y) => x+y) // List(!, !a, !ab, !abc) //foldLeft - scans the original list and constructs the new list from left to right List("a","b","c").foldLeft("!")((x,y) => x+y) // !abc List("a","b","c").scanLeft("!")((x,y) => x+y) // List(!, !a, !ab, !abc) List("a","b","c").foldLeft("!")((x,y) => y+x) // cba! List("a","b","c").scanLeft("!")((x,y) => y+x) // List(!, a!, ba!, cba!) //foldRight - scans the original list and constructs the new list from right to left List("a","b","c").foldRight("!")((x,y) => x+y) // abc! List("a","b","c").scanRight("!")((x,y) => y+x) // List(!cba, !cb, !c, !) List("a","b","c").foldRight("!")((x,y) => y+x) // !cba List("a","b","c").scanRight("!")((x,y) => y+x) // List(!cba, !cb, !c, !) /** Calculate max of an array using fold is super easy */ //we used the par method on //the collection to turn it into a parallel data collection def max(xs: Array[Int]): Int = { //instead of math.max, you can use (x, y) => if(x > y) x else y xs.par.fold(Int.MinValue)(math.max) }

-

-

Natural induction and structural induction can be performed on functional programs because functional programming allows for referential transparency. Concat on list can be proved to be associative using structural induction. The fold-unfold method for equational proof of functional programs.

Week 6 -

-

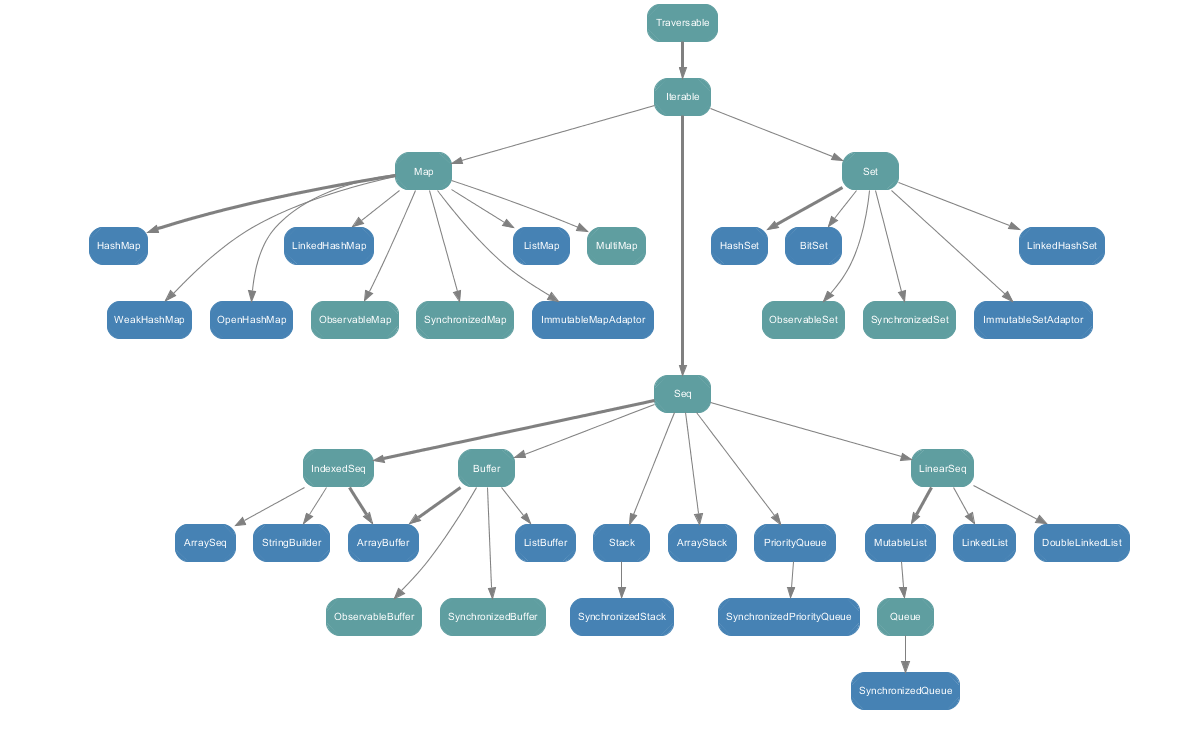

Other Collections of Sequence. List, Vector, and Range are implementation of Sequence, i.e., Sequence is a base class of List and Vector. Array and String are sequence like structures and "subclasses" of Sequence, but both came from the Java universe. Set and Map all have the base class Iterable.

-

List - O(N). Good for operations with access patterns that requires you to access head and tail sequentially. For Cons, you use

::. For concat, you use++. The fundamental operation for List is head and tail. -

Vector - O(Log_32(N)). Good for bulk operations, such as map or a fold or filter (highly parallelizable operations). You can do it in chunks of 32. For Cons, you use

+:to add element to the left of the Vector, or use:+to add element to the right of the Vector. Note that:always points to the sequence. For Vectors, the fundamental operation is index.0 +: nums //Vector(0, 1, 2, 3, -88) nums :+ 0 //Vector(1, 2, 3, -88, 0) def scalarProduct(xs: Vector[Double], ys: Vector[Double]): Double = { (xs zip ys).map{case (x,y) => x*y }.sum }

-

-

String - a sequence from the java universe java.lang.String

val s = "Hello World" s filter (c => c.isUpper) //HW s exists (c => c.isUpper) //true s forall (c => c.isUpper) //false s flatMap (c => List('.', c)) //.H.e.l.l.o. .W.o.r.l.d

-

Range

val r: Range = 1 until 5 //Range(1, 2, 3, 4) val t: Range = 1 to 5 //Range(1, 2, 3, 4, 5) 1 to 10 by 3 //Range(1, 4, 7, 10) 6 to 1 by -2 //Range(6, 4, 2) def rangePairs(m: Int, n: Int) = { (1 to m) flatMap (x => (1 to n) map (y => (x, y))) } rangePairs(3,2) //Vector((1,1), (1,2), (2,1), (2,2), (3,1), (3,2)) def isPrime(n: Int): Boolean = { (2 until n) forall (d => n % d != 0) }

-

Combinatorial Search and For-Expressions - for expressions handle nested sequences in combinatorial problems. Higher order functions on sequences often replaces loops. For nested loops, we can use for expressions. The general form is

for ( s ) yield ewhere s is a sequence of generators and filters, and e is an expression whose value is returned by an iterator. A generator is in the formp <- einstead of ( s ), braces { s } can also be used, and then the sequence of generators and filters can be written on multiple lines without requiring semicolons.def scalarProduct(xs: List[Double], ys: List[Double]): Double = { (for((x,y) <- xs zip ys) yield(x*y)).sum }

-

Combinatorial Search examples - combine Sets and for expressions in a classical combinatorial search problem. Sets are unordered, do not have duplicate elements, and the fundamental operation for Set is contains. Checkout nqueens for an example of solution generation using Vector functions (

forall,fill,updated), and for expressions. -

Map and Option - Maps provide efficient lookup of all the values mapped to a certain key. Any collection of pairs can be transformed into a

Mapusing thetoMapmethod. Similarly, anyMapcan be transformed into aListof pairs using thetoListmethod.val romanNumerals = Map('I' -> 1, 'V' -> 5, 'X' -> 10) val capitalOfCountry = Map("US" -> "Washington", "Switzerland" -> "Bern") capitalOfCountry("US") //Washington capitalOfCountry("Andorra") //NoSuchElementException capitalOfCountry get "Andorra" //> None capitalOfCountry get "US" //> Some(Washington) //With default function catches the exception and returns a default value val cap1 = capitalOfCountry withDefaultValue "<unknown>" cap1("Andorra") //<unknown> //what withDefaultValue does behind the scene def showCapitalWithOption(country: String) = capitalOfCountry.get(country) match { case Some(capital) => capital case None => "missing data" } showCapitalWithOption("US") //> Washington showCapitalWithOption("Andorra") //> missing data //To subtract something from a Map val m = Map("1" -> "a", "2" -> "b") // Map(1 -> a, 2 -> b) m - "2" // Map(1 -> a)

groupByandorderByoperations in SQL queries have analogues in Scala, namelysortWithandsorted. ThegroupBymethod takes a function mapping an element of a collection to a key of some other type, and produces aMapof keys and collections of elements which mapped to the same key.val fruit = List("apple", "pear", "orange", "pineapple") //List(apple, pear, orange, pineapple) fruit sortWith (_.length < _.length) //List(pear, apple, orange, pineapple) fruit sorted //List(apple, orange, pear, pineapple) //groupBy partitions a collection into a map of collections according to a discriminator function f fruit groupBy (_.head) //Map(p -> List(pear, pineapple), a -> List(apple), o -> List(orange))

-

In general scala collections have certain accessor combinators like

sum,fold,count, and transformer combinators likemap,flatMap, andgroupBy.

- Recursive Functions - demonstrates recursion

- Functional Sets - demonstrates Higher Order Functions

- Object Oriented Sets - demonstrates data and abstraction

- Huffman Encoding - demonstrates Pattern Matching and the scala List Collection

- Anagrams - demonstrates Collections and for expressions by solving the combinatorial problem of finding all the anagrams of a sentence.

- Reactive Cheatsheet

- Reactive Extension for JavaScript

- Reactive Programming Intro

- Functional Reactive Programming Study Guide

Week 1 -

- Partial functions - See partialfuns.sc

val f1: PartialFunction[String, String] = { case "ping" => "pong" }

//result: List(pong, 404, 404)

List("ping", "abc", "pong").map(a =>

if(f1.isDefinedAt(a)) f1(a) else "404"

)- For-expressions/for-comprehension - shortcuts for doing a flatMap, filter, then a map. Useful when you need to do nested loops. See collections.sc for how to use for expressions to implement filter, map, and flatMap, and vice versa. See json.sc and query.sc for how for expressions are useful for database query and json applications. Sets are typically used for database query or keeping track of a set of explored in graph search applications because Sets don't contain duplicates.

- Random Generators and ScalaCheck - Generator.scala has various random generators written using

scala.util.Random. generators.sc shows how it's used. - Monad - functional programming and reactive programming pattern. Three Monad Laws, Option and Try. See monad.sc. Some good articles on monads: Demystifying the Monad in Scala and Functors and Applicative

Week 2 -

- Stream - Streams are similar to Lists, but their tail is evaluated only on demand. There are three ways to create Streams:

//Notice the tail is a "?". This means the tail is not yet evaluated

Stream(1,2,3) //res: Stream(1, ?)

(1 to 3).toStream //res: Stream(1, ?)

val xs = Stream.cons(2, Stream.cons(3, Stream.empty)) //res: Stream(2, ?)

1 #:: xs //res: Stream(1, ?)Unlike the List, only the head of the Stream gets evaluated when it's first instantiated. The tail do not get evaluated until it's first needed.

def streamRange(lo: Int, hi: Int): Stream[Int] = {

print(lo+" ") //<- a side effect

if(lo >= hi) Stream.empty

else Stream.cons(lo, streamRange(lo + 1, hi))

}

/* The following will not print out "1" because the tail of the

* stream is unevaluated so it will only print out the head (i.e. 1)

*/

streamRange(1, 10).take(3)

/* The following will print out "1 2 3" as side effect because we

* are forcing all the tails of the Stream to be evaluated by making * it toList

*/

streamRange(1, 10).take(3).toListSee MyStream.scala for an implementation and Stream.sc for some examples of using Stream.

- Lazy Evaluation - Laziness means do things as late as possible and never do them twice. The later is achieved with memoization, meaning storing the result of the first evaluation and re-using the stored result instead of recomputing. This optimization is sound, since in a purely functional language, an expression produces the same result each time it is evaluated. In the case of by-name and strict evaluation, everything is recomputed. In general, lazy evaluation is a combination of by-name evaluation and memoization. See laziness.sc for some examples of lazy evaluations and infinite sequence using Streams. MyLazyStream.scala modified MyStream.scala to be lazy in the tail.

//If you run the following program, "xzyz" gets printed as a side effect

def expr = {

val x = { print("x"); 1} //val gets instantiated when you first define it

lazy val y = { print("y"); 2 } //lazy val gets instantiated only the first time you use it

def z = { print("z"); 3 } //def gets instantiated everytime you use it

z + y + x + z + y + x

} - Infinite Sequence - using Streams

// The Sieve of Eratosthenes:

def sieve(s: Stream[Int]): Stream[Int] =

s.head #:: sieve(s.tail filter (_ % s.head != 0))

val primes = sieve(from(2)) //> primes : Stream[Int] = Stream(2, ?)

primes.take(10).toList //> res4: List[Int] = List(2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29)- The water pouring problem - Program Design. Two optimizations to avoid re-computation: (1) keep a list of explored paths, pass that into the next Path calculation (2) pass the current endState to the constructor of the next Path so the next Path won't have to recompute the last Path's endState all over again using the history. See Pouring.scala and pouringTest.sc for implementation and result.

Week 3 -

- Functions and State - in a reactive program, there will be mutable states. We will broaden our definitions of functions to work with states. We have worked with pure functions have no side effects, but working with mutable states has repurcussions. The concept of time is important for mutable states. In general, objects with mutable states are identifiable through the following two observations:

- when we perform the same operation twice below, we get back different answers. This is because the history of the operation matters.

- Whenever you see

var, it should be a red flag that you are probably dealing with mutable states. Every form of mutable state is constructed from variables. Avaris like avalbut avarcan be changed later on by assignment. - Identity and Change - What it means to be equivalent - x and y are operational equivalence if no possible test can distinguish between them.

See BankAccount.scala and accounts.sc for a stateful implementation of the BankAccount.

-

Loops - While and Repeat can be translated into higher order functions Do-while loops can be implemented by making WHILE a function inside the DO class. For-loops can be implemented using for-expressions and foreach call on Ranges (1 until n). See loops.sc for the functional implementation of various loops.

-

Discrete Event Simulator (Simulation.scala and digitalCircuits.sc) which maintains a class heirarchy:

trait Simulation { type Action = () => Unit case class Event(time: Int, action: Action) //... } abstract class Gates extends Simulation { class Wire { //... } def inverter(input: Wire, output: Wire): Unit = { //... } def andGate(in1: Wire, in2: Wire, output: Wire): Unit = { //... } def orGate(in1: Wire, in2: Wire, output: Wire): Unit = { //... } def probe(name: String, wire: Wire): Unit = { //... } } abstract class Circuits extends Gates { //... } trait Parameters { def InverterDelay = 2 def AndGateDelay = 3 def OrGateDelay = 5 } object sim extends Circuits with Parameters import sim._ //...

-

An implementation of it is the digital circuit simulator in which each type of gate observes whether any input changes and if so, updates the output signal after some delay (performs action after delay).

-

Discrete Event Simlator API has performs actions specified by the user at a given moment. An

actionis a function that doesn't take any parameters and returns Unit.type Action = () => Unit

Every instance of the Simulation trait keeps an agenda of actions to perform. The agenda is a List of simulated events. Each event consists of an action and the time when it must be produced.

-

In the end, it's a tradeoff when you use mutable states. On one hand, assignments allow us to formulate certain programs in an elegant way. On the other hand, you lose referential transparency (RT) and the substitution model (tools for you to reason about the program).

-

Week 4 -

-

Imperative Event Handling (used a lot for User Interface): The Observer Pattern (e.g., publish/subscribe and model/view/controller). See BankAccountPublisher.scala, Publisher.scala, and observers.sc for an implementation of BankAccount manager using the observer pattern. This pattern has a few shortcomings.

- The Good:

- Decouples views from state and allows us to have varying number of views of a given state. And it's simple to set up.

- The Bad:

- Forces imperative style (because returns Unit as result).

- Many moving parts that need to be co-ordinated. Every subscriber has to announce itself to the publisher with subscribe and the publisher has to handle these things in the datastructure.

- Things will get more complicated when you add concurrency, e.g., when you have a view that observes two different models that get updated concurrently, then the two models can call the handler method of the view, you get race conditions.

- Another thing is views are still tightly bound to one state. Event handling can be very buggy.

- The Good:

-

Functional Reactive Programming (FRP) - reactive programming is about reacting to sequences of events that happen in time. The event sequence is aggregated into a signal. Instad of mutating states to propagate updates, we create new signals in terms of existing ones.

-

Signalis a value that you can sample at a particular point in time. Signal can be a variable. The crucial difference between a variable signal and mutable variables is that we can define relationship between two signals and when one changes, the other automatically changes. There are no such mechanisms for mutable variables and they must be updated manually. See BankAccountPublisher.scala and signal.sc for examples of using Signals to maintain states.//assign constant value to a signal val sig = Signal(3) //There are two ways to update a Variable signal val sig = Var(3) sig.update(5) sig() = 5 /** Key difference between mutable variables and signal variables */ //mutable varialbes var a = 2 var b = 2 * a a = a + 1 b // still 4. Not automatically updated to 6 //signal variables val aSig: Var[Int] = Var(2) // signal variable of 2 val bSig: Var[Int] = Var(2 * aSig()) //signal variable of 2 * the value of aSig bSig() // to "dereference" the bSig, we get 4 aSig.update(3) bSig() // the value of bSig at current time is automatically updated to 6! //Constant vs. variable signals val x = Var(1) val y = Signal(x() * 2) // when using Signal(), definition cannot be changed x() // 1 y() // 2 val x1 = x() + 1 x() = x1 x() // 2 y() // 4 /** cyclic signal definition. * s() = s() + 1 makes no sense because you * are trying to define a signal s to be at all points in time larger than itself. */ //ERROR val x = Var(1) x() = x() + 1 // cyclic signal definition //CORRECT val x = Var(1) val x1 = x() + 1 x() = x1 // updates x() to be Var(2) /** Caveats with Signals * moral of the story is don't use var and use s.update(v) instead of s() = v to * minimize chance of mistake. */ val num = Var(1) val twice = Signal(num() * 2) num() = 2 twice() // 4 var num2 = Var(1) val twice2 = Signal(num2() * 2) num2 = Var(2) twice2() // 2

-

Implementation of

SignalandVar, which is a subclass ofSignalin Signal.scala. Each signal maintains its current value, the current expression that defines the signal value, and a set of observers (i.e., the other signals that depend on its value.- The first implementation of Signal relies on a global variable

caller, which is a stack. Global variables in concurrency are bad news (results in race conditions). One way to deal with that is to use synchronization. - For synchronization, replace global variable by thread local state, i.e., use

scala.util.DynamicVariable. Thread-local state means each thread accesses a separate copy of a variable. Thread-local state is an improvement to the unprotected global variable, but it has its own problems (fundamentally imperative, use of threads could create deadlock, its implementation on JDK involves a slow global hash table lookup). - Another solution involves implicit parameters. Instead of maintaining a thread-local variable, pass its current value into a signal expression as an implicit parameter.

- The first implementation of Signal relies on a global variable

-

Latency as Effect - Computation can take time. Futures.

-

Future Topics:

- Threads are how you do concurrency, but threads are really low levels and dangerous. Some good abstractions of Threads a Futures, Reactive Streams, and Actors using Akka.

- Using Parallel data structures and parallel algorithms to use multi-threadedness to gain efficiency.

- If we want to scale parallelism beyond what a single computer can do, then we arrive at distributed programs. Important topics are data analysis and big data using Apache Spark. Spark can be seen as a framework for distributed scala collections.

- Bloxorz - get practice on lazy evaluation, for-expression, Stream, and DFS/BFS graph search algorithms. You are solving a

- Quickcheck - demonstrates functions and state

- Calculator - demonstrates timely effects and implement UI using

Signal. Hint: dependent signals must be fully wrap the signal upon which it depends (including all calculations). Do not assign signal values to intermediate valuesval. To store intermediary calculations using signal, assign intermediaries todef. Wrap every atomic computation involing signal values in parentheses.- To run compile and run the webUI page with output in console:

sbt > webUI/fastOptJS

- To run compile and run the webUI page with output in console:

Week 1 -

- Deadlock

- Consider a multi-threaded program with two threads A and B, in which these two threads perform calculations using global mutable values that gets passed around and mutated by both threads. Because we can’t don’t know for sure when thread B is going to be called, we are dealing with uncertainty about the value of the object we are working on. While it is possible to bring order by imposing strict rules regarding resource access and mutation, this workaround (commonly referred to as Synchrnous Programming) comes at a high cost in performance and additional layers of complexity in the software and hardware to have to manage the policy layer. Good reading on this topic: Benjamin Erb’s Diploma Thesis

- Parallelism on the JVM

- First Class Tasks

Week 2 -

-

Task parallelism (big idea: create reduction tree):

a form of parallelizaton that distributes execution processes across computing nodes.

-

Parallel map - implement using a Tree:

def parMap[A: Manifest, B: Manifest](t: Tree[A], f: A => B): Tree[B] = t match { //match on shape of the tree case Leaf(a) => { //...A sequential map of array producing an array using a loop. } case Node(l, r) => { //do parallel for the large cases, i.e., Node val (lb, rb) = parallel(parMap(l, f), parMap(r, f)) Node(lb, rb) } }

-

Parallel fold and reduce - implement using a Tree.

def parReduce[A](t: FoldTree[A], f: (A,A) => A): A = t match { case Leaf(v) => v case Node(l,r) => { val (lb, rb) = parallel(parReduce(l, f), parReduce(r,f)) f(lb, rb) } }

Associative property is important here.

-

Parallel scan - requires upsweep and downsweep and a Tree consisting of a

Leaf,Nodeand aNodeRes, which allows the Trees storing intermediate value in Node.sealed abstract class ScanTreeRes[A] { val res: A } case class LeafRes[A](override val res: A) extends TreeRes[A] case class NodeRes[A](l: TreeRes[A], override val res: A, r: TreeRes[A]) extends TreeRes[A] case class Node[A](l: TreeRes[A], override val res: A, r: TreeRes[A]) extends TreeRes[A] def upsweep[A](inp: Array[A], from: Int, to: Int, f: (A,A) => A): ScanTreeRes[A] = { if(to - from < threshold) Leaf(from, to, reduceSeg(inp, from + 1, to, inp(from), f)) //imperative solution using loop else { val mid = from + (to - from) / 2 val (tL, tR) = parallel(upsweep(inp, from, mid, f), upsweep(inp, mid, to, f)) Node(tL, f(tL.res, tR.res), tR) } } def downsweep[A](inp: Array[A], a0: A, f: (A, A) => A, t: TreeRes[A], out: Array[A]): Unit = t match { case Leaf(from, to, res) => scanLeftSeg(inp, from, to, a0, f, out) //imperative solution using loop case Node(l, _, r) => { val (_, _) = parallel(downsweep(inp, a0, f, l, out), downsweep(inp, f(a0, l.res), f, r, out)) } }

Week 3 -

-

Data parallelism

a form of parallelization that distributes data across computing nodes.

Data parallelism provides significant speedup over Task parallelism when the work is not constant.

-

parallel for-loop - Scala collections can be converted to parallel collections by invoking the

.parmethod. Subsequent data parallel operations are executed in parallel://a program that checks for palindrome (1 until 1000).par .filter(n => n % 3 == 0) .count(n => n.toString == n.toString.reverse)

Data Parallelism does not work for

foldLeft,foldRightscanLeft,scanRight,reduceLeft, andreduceRightoperations because these processes process elements sequentially. In order to use data-parallelism, we have to usefold,scan, andreduce.def foldLeft(z: A)(f: (B, A) => B): B //can't have data parallelism def fold(z: A)(f: A, A) => A): A //can have data parallelism

-

foldLeftis more expressive thanfold, howeverfoldallows for data parallelization, with the condition that the neutral elementzand the binary operatorfmust form a monoid.zmust be the same type as the members of the collection and thefoperator must be associative for the program to work correctly.def fold(z: A)(f: A, A) => A): A def foldLeft(z: A)(f: (B, A) => B): B def fold(z: A)(op: (A,A) => A): A = foldLeft[A](z)(op) /** Example showing the difference between fold and foldLeft */ //The following program does not compile -- z is 0 and not a Char Array('E', 'P', 'F', 'L').par.fold(0)((count, c) => if(isVowel(c)) count+1 else count) //However, foldLeft compiles because for foldLeft, z element does not //have to be the same type as the elements in the array Array('E', 'P', 'F', 'L').foldLeft(0)((count, c) => if(isVowel(c)) count+1 else count) def isVowel(c: Char): Boolean = List('a','e','i','o','u') exists (a => a == Character.toLowerCase(c))

-

aggregateaddresses the shortcomings of both the fold (not expressive) and foldLeft (no data parallelization). Theaggregateoperation is defined as:def aggregate[B](z: B)(f: (B,A) => B, g: (B, B) => B): B

how it works is it divides the data into many smaller parts for mutiple processors to compute via foldLeft. Then it combines back into a form similar to fold. The parallel reduction operator and the neutral element form a monoid.

// Use aggregate to count the number of vowels in an array Array('E', 'P', 'F', 'L').par.aggregate(0)( (count, c) => if(isVowel(c)) count + 1 else count, _ + _ )

-

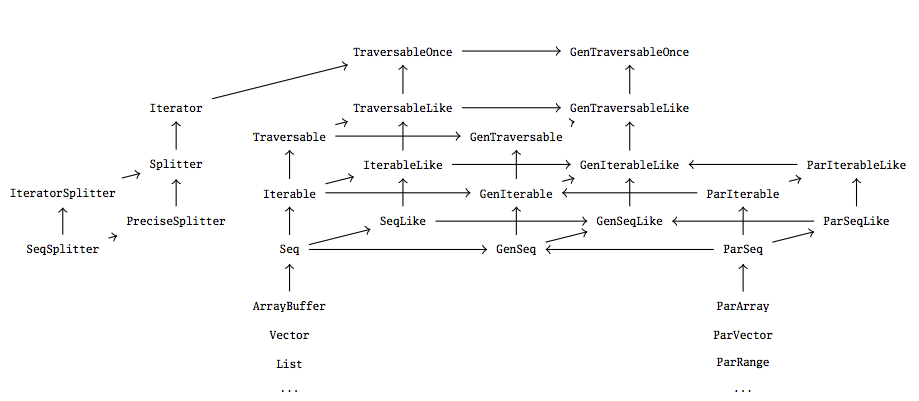

- Sequential traits

Traversable[T]- collection of elements with type T, with operations implemented usingforeach.Iterable[T]- collection of elements with type T, with operations implemented usingiterator.Seq[T]- an ordered sequence of elements with type T.Set[T]- a set of elements with type T (no duplicates).Map[K,V]- a map of keys with type K associated with values of type V (no duplicate keys).

- Parallel Counterpart traits -

ParIterable[T],ParSeq[T],ParSet[T], andParMap[K,V]. - For code that is agnostic about parallelism, there exists a separate hierarchy of generic collection traits

GenIterable[T],GenSeq[T],GenSet[T]andGenMap[K,V]. A generic collection type, such as GenSeq or GenMap, can be implemented either with a parallel or a sequential collection. This means that the classify method will either run sequentially or in parallel, depending on the type of the collection that is passed to it, and returns a sequential or a parallel map, respectively. The method is oblivious to whether the algorithm is parallel or not. - Not thread-safe:

mutable.Map[K,V]. - Thread-safe:

TrieMap[K,V]- thesnapshotmethod can be used to efficiently grab the current state by creating a copy of the current state. - Rules:

- Never write to a collection that is concurrently traversed.

- Never read from a collection that is concurrently modified.

- Don't mutate collection states without synchronization.

- Look for ways to use the correct combinator to solve the problem via pure functions - No side effect gives deterministic and correct data-parallel operation (deterministic programs that don't crash).

- Sequential traits

-

Data Parallel Abstractions - iterator, splitter, builders, combiners.

Week 4 -

- Implementation of Combiners - picking datastructures that are more amenable to parallelization.

-

Transformer operation is a collection operation that creates another collection, instead of adjusting a single value. Methods such as

filter,map,flatMap, andgroupByare examples of transformer operations. Methods such asfold,sum, andaggregateare not transformer operations.//Builders can only implement sequential transformer operations trait MyBuilder[A, Repr] { //The `+=` adds the items into the collection sequentially def +=(elem: A): MyBuilder[A, Repr] def result: Repr //obtains the resulting sequence } //Combiners implement parallel transformer operations //When Repr is a Set or a Map, combine represents a Union //When Repr is a sequence, combine represents concatenation trait MyCombiner[A, Repr] extends MyBuilder[A, Repr] { def combine(that: MyCombiner[A, Repr]): MyCombiner[A, Repr] }

-

Constructing datastructures in parallel requires an efficient

combineoperation. Why? Because we are copying things multiple times to create the sub-problems for the multicore computer to process in parallel and merging things back into the final result. The act of copying takes time. -

We cannot implement an efficient

combineoperation for Arrays. -

Worst case lookup time:

- Hash tables - O(1)

- balanced tree - O(log n)

- Linked list - O(n)

-

However, most data structures can be construted in parallel using two-phase constructure, where the intermediary datastructures are ArrayBuffers, Hash tables, balanced trees, or quad trees (for partitioning the data based on their spatial coordinates).

-

- Conc-tree Data Structure -

- Box Blur Filter - demonstrates Tasks

- boxBlurKernel - this method computes the blurred RGBA value of a single pixel of the input image

- HorizontalBoxBlur - singleton which implements methods blur and parBlur to blur horizontal pixels of the image in parallel

- VerticalBoxBlur - singleton which implements methods blur and parBlur to blur vertical pixels of the image in parallel

- To run the ScalaShop program, in the console:

sbt > runMain scalashop.ScalaShop

- Reductions and Prefix Sums - demonstrates basic task parallel algorithms

- K-Means - demonstrates Data-Parallelism

- Barnes-Hut Simulation - demonstrates data structures for Parallel Computing