Department of Symbolic Systems, Stanford University

Department of Mathematical & Computational Science, Stanford University

Our focus for this project is using machine learning to build a classifier capable of sorting people into their Myers-Briggs Type Index (MBTI) personality type based on text samples from their social media posts. The motivations for building such a classifier are twofold. First, the pervasiveness of social media means that such a classifier would have ample data on which to run personality assessments, allowing more people to gain access to their MBTI personality type, and perhaps far more reliably and more quickly. There is significant interest in this area within the academic realm of psychology as well as the private sector. For example, many employers wish to know more about the personality of potential hires, so as to better manage the culture of their firm. Our second motivation centers on the potential for our classifier to be more accurate than currently available tests as evinced by the fact that retest error rates for personality tests administered by trained psychologists currently hover around 0.5. That is, the there is a probability of about half that taking the test twice in two different contexts will yield different classifications. Thus, our classifier could serve as a verification system for these initial tests as a means of allowing people to have more confidence in their results. Indeed, a text-based classifier would be able to operate on a far larger amount of data than that given in a single personality test.

-

Download dataset from https://www.kaggle.com/datasnaek/mbti-type and place here: data/mbti_1.csv

-

Download GloVe word vectors from https://www.kaggle.com/watts2/glove6b50dtxt?select=glove.6B.50d.txt and place here: data/glove.6B.50d.txt

-

Run these scripts in order to generate dataset: separate_clean_and_unclean.py, make_training_set.py, make_test_set.py

-

Run baseline.py to use a naive Bayes classifier to establish a lower bound of reasonable accuracy

-

Run rnn.py with the constants / control variables that you want.

-

Run trump_predictor.py for fun

-

Run differentiate_words.py and then word_cloud.py to get data for word cloud formation for each MBTI type letter (i.e. one for I, one for E, etc.)

-

Above all, make this your own. I developed this project when I was not very good at programming, so it is filled with bad style. Enjoy!

In the scientific field of psychology, the concept of personality is considered a powerful but imprecisely defined construct. Psychologists would therefore stand to gain much from the development of more concrete, empirical measures of extant models of personality. Our project seeks to improve the understanding of one such model: the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). We intend to use machine learning to build a classifier that will take in text (e.g. social media posts) as input and produce as output a prediction of the MBTI personality type of the author of said text. A successful implementation of such a classifier would demonstrate a strong linguistic basis for MBTI and potentially personality in general. Furthermore, the ability to produce an accurate text-based classifier has significant potential implications for the field of psychology itself, since the connection between natural language and personality type is non-trivial [11]

The MBTI personality classification system grew out of Jungian psychoanalytic psychology as a systematization of archetypal personality types used in clinical practice. The system is divided along four binary orthogonal personality dimensions, altogether comprising a total of 16 distinct personality types.

The dimensions are as follows:

i. Extraversion (E) vs Introversion (I): a measure of how much an individual prefers their outer or inner world.

ii. Sensing (S) vs Intuition (N): a measure of how much an individual processes information through the five senses versus impressions through patterns.

iii. Thinking (T) vs Feeling (F): a measure of preference for objective principles and facts versus weighing the emotional perspectives of others.

iv. Judging (J) vs Perceiving (P): a measure of how much an individual prefers a planned and ordered life versus a flexible and spontaneous life.

There is current debate over the predictive validity of MBTI regarding persistent personality traits. In contrast to the MBTI system, the prevalent personality type system used in Psychometrics is the Big Five personality classification system. This personality system measures along five statistically orthogonal personality dimensions: Extraversion, Agreeableness, Openness, Conscientiousness, and Neuroticism. In contrast to MBTI, the Big Five personality type system is statistically derived to have predictive power over measurable features in an individual’s life, ie. income, education level, marital status, and is stable over an individuals lifetime. However work by Pennebaker, J. W. and King, L. A [10] indicates significant correlations between four of the Big Five personality traits and the four MBTI dimensions: Agreeableness with Thinking/Feeling; Conscientiousness with Judging/Perceiving; Extraversion with Extraversion/Introversion; and Openness with Sensing/Intuition. These correlations indicate a relative mapping of MBTI personality traits to persistent features of personality. In the context of our project and the popularity of the MBTI personality system, these correlations justify an attempt to model the relationship between writing style and persistent personality traits. Current research on predicting MBTI personality types from textual data is sparse. Nevertheless important strides have been made in both machine learning and neuroscience. Work by Jonathan S. Adelstein [5] has discovered the neural correlates of the Big Five personality domains. Specifically, the activation patterns of independent functional subdivisions in the brain, responsible for cognitive and affective processing, were shown to be statistically different among individuals differing on the various Big Five personality dimensions. Likewise there was a functional overlap between these identified regions responsible for differences in personality type and written communication. This justifies our attempt at predicting persistent personality traits from textual data. In the field of Machine Learning, deep feed forward neural networks have proven useful in successfully predicting MBTI personality types for relatively small textual datasets. Work by Mihai Gavrilescu [6] and Champa H N [9] used a three layer feed forward architecture on handwritten textual data. Although their models incorporated handwritten features in addition to just textual characters, and suffered from small sample sizes, they are nonetheless a proof of concept that deep neural architectures are quite capable of predicting MBTI with considerable accuracy. Alternatively work by Mike Komisin and Curry Guinn [8] using classical machine learning methods, including Naive Bayes and SVM, on word choice features using a bag-of-words model, were able to accurately predict MBTI personality type as well. Their research indicates that textual data alone is sufficient for predicting MBTI personality types, even if not using state-of-the-art methods. Altogether past work on this topic indicates a ripe opportunity to combine newer deep learning techniques with massive textual datasets to accurately predict individual persistent personality traits.

When we examined other studies of MBTI using machine learning, we were surprised to find that researchers rarely made a point of cleaning their data set to accord with the actual proportions of MBTI types in the general population (e.g. ISTJ = 0.11, ISFJ = 0.09, etc.)[3]. Since our raw data set is severely disproportional (see fig. 1) compared to the roughly uniform distribution for the general population, it was clear to us that some cleaning of the proportional representation of each MBTI type would be necessary. Therefore, we artificially made our test set reflect the proportions found for each type in the general population, so as to prevent any misinterpretation of results due to skewed representation of classes in the test set.

Figure 1: Non-uniform representation of MBTI types in the data set:

Since the data set comes from an Internet forum where individuals communicate strictly via written text, some word removal was clearly necessary. For example, there were several instances of data points containing links to websites. Since we want our model to generalize to the English language, we removed any data points containing links to websites. Next, since we want every word in the data to be as meaningful as possible, we removed so-called ”stop words” from the text (e.g. very common filler words like ”a”, ”the”, ”or”, etc.) using python’s NLTK. Finally, since the particular data set we are working with comes from a website intended for explicit discussion of personality models, especially MBTI, we removed types themselves (e.g. ’INTJ’, ’INFP’, etc.), so as to prevent the model from ”cheating” by learning to recognize mentions of MBTI by name.

We used nltk.stem.WordNetLemmatizer to lemmatize the text, meaning that inflected forms of the same root word were transformed into their dictionary form (e.g. ”walking”, ”walked”, ”walk” all become ”walk”). This will allow us to make use of the fact that inflected forms of the same word still carry one shared meaning.

Using a Keras word tokenizer, we tokenized the 2500 most common words of the lemmatized text. That is, the most common word became 1, the second most common word became 2, etc. all the way to 2500. Any other words in the lemmatized text were removed, such that at this point the text is in the form of lists of integers (with a vocabulary of 1-2500).

Since the tokenized posts are of highly variable lengths, it is necessary to make them all the same number tokens long. We achieved this by ”padding” every tokenized post such that it has exactly 40 integers. That is, if there are less than 40 integers in the tokenized post we add zeros until it has 40 tokens, and if there are more than 40 tokens we remove tokens from the post until it has 40 tokens. At this point, our input is ready.

For our embedding layer, we use an embedding matrix in the form of a dictionary mapping every lemmatized word (following the same process described above up to lemmatization) to the 50- dimensional GloVe representation of that word. This produces an output of size 50 for every padded input vector.

Due to the fact that our data set is composed of sequential text data, we decided to use a recurrent neural network in order to capture some of the information in the text data that would otherwise be ignored (e.g. as with a naive Bayes classifier).

We experimented with various types of recurrent neural networks (RNN) for this step. After testing the SimpleRNN, GRU, LSTM, and Bidirectional LSTM options for recurrent layers in Keras, we found the LSTM option to give the best results.

We further found the best parameters for the LSTM layer to be dropout of 0.1, recurrent dropout of 0.1, sigmoid activation, and a zero kernel initializer.

Finally, we use a dense layer with sigmoid activation to produce a value between 0 and 1, representing the predicted class probability, since there are only two classes.

Furthermore, we use binary crossentropy for the loss function (since there are only two classes) and an Adam optimizer.

Our main data set is a publicly available Kaggle data set containing 8600 rows of data [2]. Each row consists of two columns: (1) the MBTI personality type (e.g. INTJ, ESFP) of a given person, and (2) fifty of that persons social media posts. Since there are fifty posts included for every user, the number of data points is 430,000. This data comes from the users of personalitycafe.com, an online forum where users first take a questionairre that sorts them into their MBTI type and then allows them to chat publicly with other users.

Due to the nature of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, we can break down the classification task with 16 classes into four smaller binary classification tasks. This is because an MBTI type is composed of four binary classes, where each binary class represents a dimension of personality as theorized by the inventors of the MBTI personality model. Therefore, instead of training a multi-class classifier, we instead train four different binary classifiers, such that each specializes in one of the dimensions of personality.

The following hyperparameter configurations were found to produce the best performance during testing.

Learning rate: 0.001

Model batch size: 128

Number of epochs: 30

Token vocabulary size: 2500

Input vector length: 40

Embedding vector length: 50

For post classification, we preprocessed the test set and predicted the class for every individual post. We then produced an accuracy score and confusion matrix for every MBTI dimension.

In order to classify users, we needed to find a way of turning class predictions of individual posts all authored by an individual into a prediction for the class of the author. We devised two different methods to accomplish this, one of which was more effective than the other.

The first method is to assign the most common class prediction for a given user’s corpus of posts as that user’s predicted MBTI class.

The second method is to take the mean of the class probability predictions for all the posts in a user’s corpus and round either to 0 or 1.

The second method proved more effective (by one or two percentage points of accuracy), and so we utilize it for our reported findings.

Accuracy:

Confusion matrices:

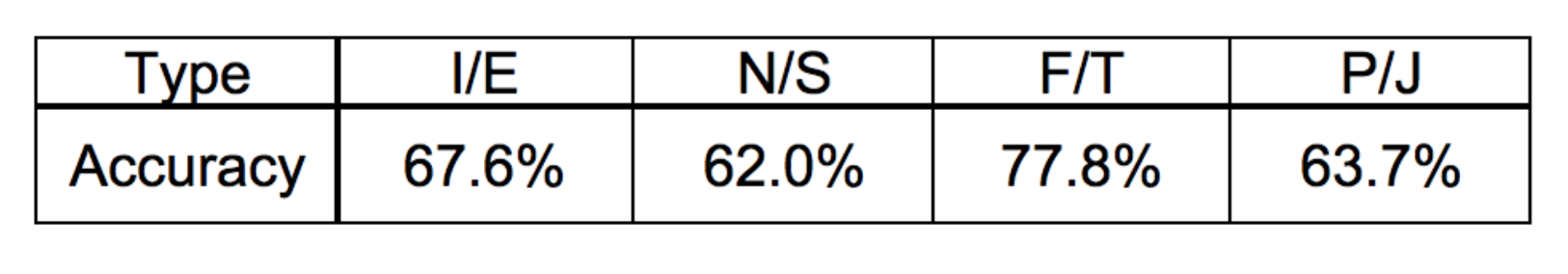

Accuracy:

Confusion matrices:

A quick glance at the classification accuracy results for both the Post Classification and User Classification reveals that User Classification performed with a higher accuracy score across all four personality dimensions than Post Classification. Alternatively, the confusion matrices indicate the same confusion pattern along the N/S and P/J dimensions for both Post Classification and User Classification. Along the N/S dimension and P/J, treating N (or P) as positive and S (or J) as negative, we have more False Positives than False Negatives. This indicates a propensity for our model to incorrectly predict N (or P) over incorrectly predicting S (or J).

When classifying individual social media posts, the model struggled to accurately predict the binary class for each MBTI personality dimension. However, when one considers the brevity of the text and the inherent difficulty in gleaning underlying information in such brief text, our achieved accuracy actually seems impressive. After all, it is hard to believe that there is huge separation in the ways people of even vastly different personalities use language that is discoverable in individual social media posts of relatively short length.

Next, when classifying users based on their several social media posts, the model achieved consid- erable success in accurately predicting the binary class for each MBTI personality dimension. The working assumption that allowed us to accurately classify users was that the their individual posts retained information on the microscopic level that when considered all together would indicate the macroscopic character of the author’s personality type. That is, the averaging of the probability predictions of individual social media posts proved to be an effective indicator of the author’s actual personality type.

For data visualization, we produced word clouds for concepts most prevalently used by specific classes of the personality dimensions. These were created by extracting the posts with the most extreme class probability predictions (500 for each binary class). In the case of words shared between both extractions for a given dimension, the extraction with the smaller number of instances of that word had all its instances of that word removed and the other extraction had the same number of instances of that word removed (in order to better capture the disproportionate use of certain words by certain types). Only then are these word clouds created, where the size of each word is proportional to its appearance frequency in the respective extractions. We consider these word clouds to be illustrative of some of the unique ways different MBTIs use language.

Our classifier should perform better as the amount of individual social media posts available for a given user increases. This is because the presumed differences that affect the person’s use of language become more apparent as the amount of text they provide increases. While our test set only provided up to 50 posts for a given user, it is obviously possible to obtains several hundred or even thousands of such pieces of text for a given social media user, thereby drastically improving our ability to classify their MBTI.

As a real life test case of this hypothetical capability for greater abstraction with increased quantity of text data, we decided to scrape 30,000 of Donald Trump’s tweets and use our model to predict his MBTI type. Our model produced the following average of the probabilities for each personality dimension:

Rounding from these numbers, our model predicts that Donald Trump’s MBTI type is ESTP, which is his true MBTI type according to MBTI experts [4]. To drive this point home, it should be noted that the ESTP archetype is known as ”the Entrepreneur”! [1] This is just one example, but at the very least it demonstrates the expansive areas of application available to text classifiers like the one we have developed.

The overall accuracy of our trained model when classifying users is 0.208 (0.676 x 0.62 x 0.778 x 0.637). While this seems to indicate a weak overall ability of our model to correctly classify all four MBTI dimensions, it should be noted that this number represents perfect classification, and that it does not demonstrate the effectiveness of our model to achieve approximate predictions of overall MBTI types. In fact, other models that focus on multi-class classification of MBTI may achieve higher accuracy of perfect classification, but they do so at risk of getting their prediction completely wrong. That is, multi-class classification treats all classes as independent of each other, and so they fail to capture to in-built relatedness of some types to other types (e.g. INFP is much more similar to INTJ than it is to ESTJ). That being said, our model represents a trade-off of these two aspects: we achieve lower rates of perfect classification in exchange for higher rates of approximately correct classification (i.e. ”good” classification).

[1] Estp archetype. https://www.16personalities.com/estp-personality.

[2] Mbti kaggle data set. https://www.kaggle.com/datasnaek/mbti-type.

[3] Mbti representation in the general population. http://aiweb.techfak.uni-bielefeld. de/content/bworld-robot-control-software/.

[4] Trump’s mbti. https://www.kaggle.com/datasnaek/mbti-type.

[5] Jonathan S. Adelstein, Zarrar Shehzad, Maarten Mennes, Colin G. DeYoung, Xi-Nian Zuo, Clare Kelly, Daniel S. Margulies, Aaron Bloomfield, Jeremy R. Gray, F. Xavier Castellanos, and Michael P. Milham. Personality is reflected in the brain’s intrinsic functional architecture. PLOS ONE, 6(11):1–12, 11 2011.

[6] Mihai Gavrilescu. Study on determining the myers-briggs personality type based on individual’s handwriting. The 5th IEEE International Conference on E-Health and Bioengineering, 11 2015.

[7] Mayuri P. Kalghatgi, Manjula Ramannavar, and Dr. Nandini S. Sidnal. A neural network approach to personality prediction based on the big-five model. International Journal of Innovative Research in Advanced Engineering, 2015.

[8] M Komisin and Curry Guinn. Identifying personality types using document classification methods. Proceedings of the 25th International Florida Artificial Intelligence Research Society Conference, FLAIRS-25, pages 232–237, 01 2012.

[9] ChampaHNandDr.KRAnandakumar.Artificialneuralnetworkforhumanbehaviorprediction through handwriting analysis. International Journal of Computer Applications, 2010.

[10] James W Pennebaker and Laura A King. Linguistic styles: Language use as an individual difference. Journal of personality and social psychology, 77(6):1296, 1999.

[11] K. R. Scherer. Personality markers in speech. Cambridge University Press., 1979.