-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 341

Lesson Save your Code Revisions Forever with Git

Created by Rafase282

Github | FreeCodeCamp | CodePen | LinkedIn | Website | E-Mail

All the material was directly obtained from this page: http://jlord.us/git-it/index.html

After you learn how to use git, here are other resources to help you learn more about git:

- Creating a New Github Issue

- Git Blame

- Git Merge

- Git Rebase

- Other Git Resources

- Writing Great Git Commit Messages

- Using GitHub Pages for your front end dev projects

- Search your issue on GitHub

- How Issue Mods Work

Credit where is due!

Windows: It's recommended to download GitHub for Windows, which includes Git and has an easier install: windows.github.com. Use the Git Shell for your terminal.

Mac: You can also download GitHub for Mac, which includes Git, mac.github.com (from Preferences, select the command line tools install), or

- download Git by itself at: git-scm.com/downloads and follow the installation instructions.

Git isn't like other programs on your computer. You'll likely not see an icon on your desktop, but it will always be available to you and you'll be able to access it at anytime from your terminal (which you're using in Git-it!) or Git desktop applications (like GitHub for Mac or Windows).

Once it is installed, open terminal (aka Bash, aka Shell, aka Prompt). You can verify that it's really there by typing:

$ git --version

This will return the version of Git that you're running and look something like this:

git version 1.9.1

(Any version 1.7.10 or higher is fine.)

Next, configure Git so it knows who to associate your changes to:

Set your name:

$ git config --global user.name "<Your Name>"

Now set your email:

$ git config --global user.email "[[email protected]](mailto:[email protected])"

A repository is essentially a project. You can imagine it as a project's folder with all the related files inside of it. In fact, that's what it will look like on your computer anyways.

You tell Git what your project is and Git will start tracking all of the changes to that folder. Files added or subtracted or even a single letter in a single file changed -- all of it's tracked and time stamped by Git. That's version control.

Terminal (or Bash) is a way of using your computer by just typing commands. You can rename files, open files, create new folders, and move between directories (folders) all by typing out commands. You can even run a text editor (such as Vim) in your terminal and never have to leave!

Besides navigating your computer, you can also use programs in Terminal that have a command-line interface (CLI), meaning they can be run with commands in terminal. Git-it is one, you're using terminal to use it! Git is another. You can access and control Git through commands in terminal, as you'll be doing very soon!

In Git-it you'll learn a few basic command line actions which will be described within the steps.

You're going to create a new folder and initialize it as a Git repository.

To make things easier, name your folder what you'd name the project. How about 'hello-world'.

You can type these commands one at a time into your terminal window.

To make a new folder:

$ mkdir hello-world To go into that folder:

$ cd hello-world To create a new Git instance for a project:

$ git init That's it! It will just return you to a new line. If you want to be double-sure that it's a Git repository, type git status and if it doesn't return 'fatal: Not a git repository...', you're golden!

Now that you've got a repository started, add a file to it.

Open a text editor. Now write a couple of lines of text, perhaps say hello, and save the file as readme.txt in the 'hello-world' folder you created in the last challenge.

Next check the status of your repository to find out if there have been changes. Below in this terminal, you should still be within the 'hello-world' you created. See if there are changes listed:

$ git status

Then add the file you just created to the files you'd like to commit (aka save) to change.

$ git add readme.txt

Finally, commit those changes to the repository's history with a short description of the updates.

$ git commit -m "<your commit message>"

Now add another line to readme.txt and save.

In terminal, you can view the difference between the file now and how it was at your last commit.

$ git diff

Now with what you just learned above, commit this latest change.

The repository you've created so far is just on your computer, which is handy, but makes it pretty hard to share and work with others on. No worries, that's what GitHub is for!

GitHub is a website that allows people everywhere to upload what they're working on with Git and to easily work together.

Visit github.com and sign up for a free account. High five, welcome!

Add your GitHub username to your Git configuration, which will be needed in order to verify the upcoming challenges. Save it exactly as you created it on GitHub -- capitalize where capitalized, and remember you don't need to enter the "<" and ">" .

Add your GitHub username to your configuration:

$ git config --global user.username <USerNamE>

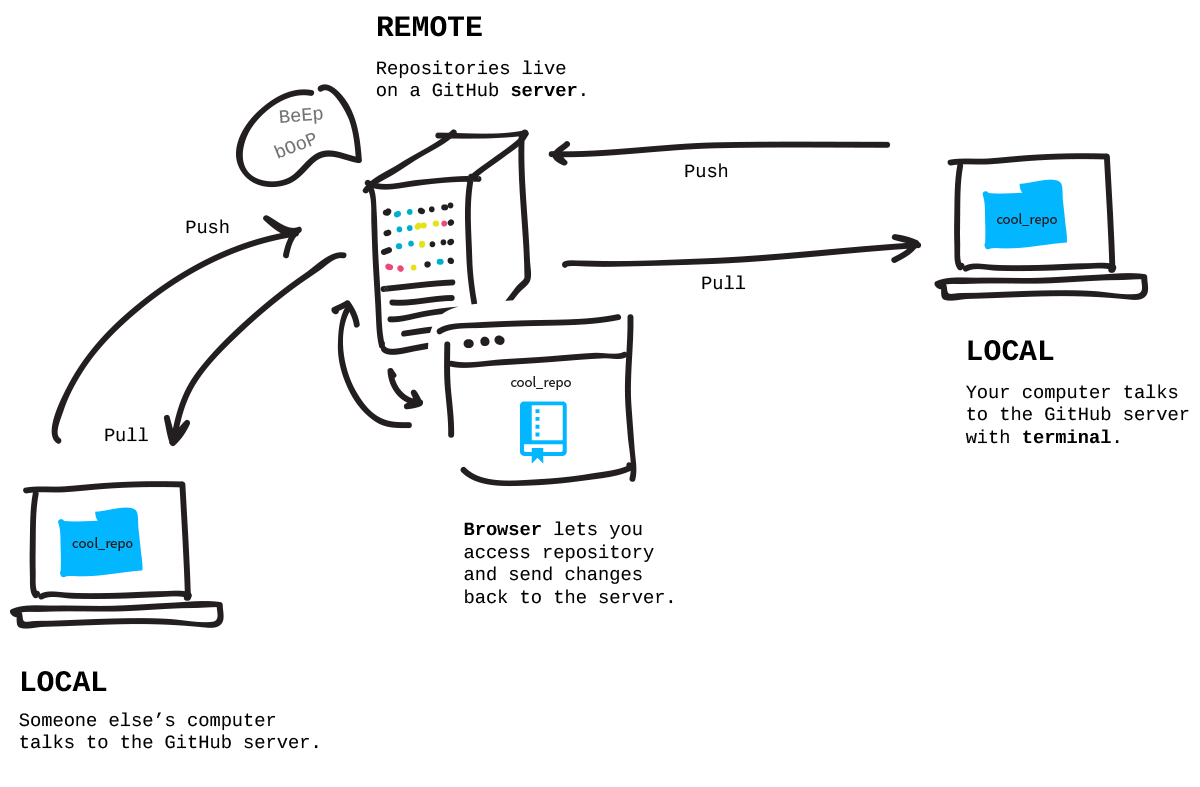

When you put something on GitHub, that copy lives on one of GitHub's servers. This makes it a remote repository because it is not on your computer, but on a server, "remote" and somewhere else. By pushing your local (on your computer) changes to it, you keep it up to date.

Others can always get the latest from your project by pulling your changes down from the remote (and onto their computer). This is how everyone can work on a project together without needing access to your computer where your local copy is stored.

You want to sync your local version with one stored on GitHub.com called the remote version. So first create an empty remote repository on GitHub.com.

- Go to github.com, log in, and click the '+' in the top right to create a new repository.

- Give it a name that matches your local repository's name, 'hello-world', and a short description.

- Make it public.

- Don't initialize with a README because we already have a file, locally, named 'readme.txt'.

- Leave .gitignore and license on 'none'.

- Click create repository!

These are common files in open source projects.

A readme explains what the project is, how to use it, and often times, how to contribute (though sometimes there is an extra file, CONTRIBUTING.md, for those details).

A .gitignore is a list of files that Git should not track, for instance, files with passwords!

A license file is the type of license you put on your project, information on the types is here: http://www.choosealicense.com/

We don't need any of them, however, for this example.

Now you've got an empty repository started on GitHub.com. At the top you'll see 'Quick Setup', make sure the 'HTTP' button is selected and copy the address -- this is the location (address) of your repository on GitHub's servers.

Back in your terminal, and inside of the 'hello-world' folder that you initialized as a Git repository in the earlier challenge, you want to tell Git the location of the remote version on GitHub's servers. You can have multiple remotes so each requires a name. For your main one, this is commonly named origin.

$ git remote add origin <URLFROMGITHUB>

Your local repository now knows where your remote one named 'origin' lives on GitHub's servers. Think of it as adding a name and address on speed dial -- now when you need to send something there, you can.

A note:

If you have GitHub for Windows on your computer, a remote named 'origin' is automatically created. In that case, you'll just need to tell it what URL to associate with origin. Use this command instead of the 'add' one above:

$ git remote set-url origin <URLFROMGITHUB>

Next you want to push (send) everything you've done locally to GitHub. Ideally you want to stay in sync, meaning your local and remote versions match.

Git has a branching system so that you can work on different parts of a project at different times. We'll learn more about that later, but by default the first branch is named 'master'. When you push (and later pull) from a project, you tell Git the branch name you want and the name of the remote that it lives on.

In this case, we'll send our branch named 'master' to our remote on GitHub named 'origin'.

$ git push origin master

Now go to GitHub and refresh the page of your repository. WOAH! Everything is the same locally and remotely. Congrats on your first public repository!

###Forks

Now you've made a project locally and pushed it to GitHub, but that's only half the fun. The other half is working with other people and projects.

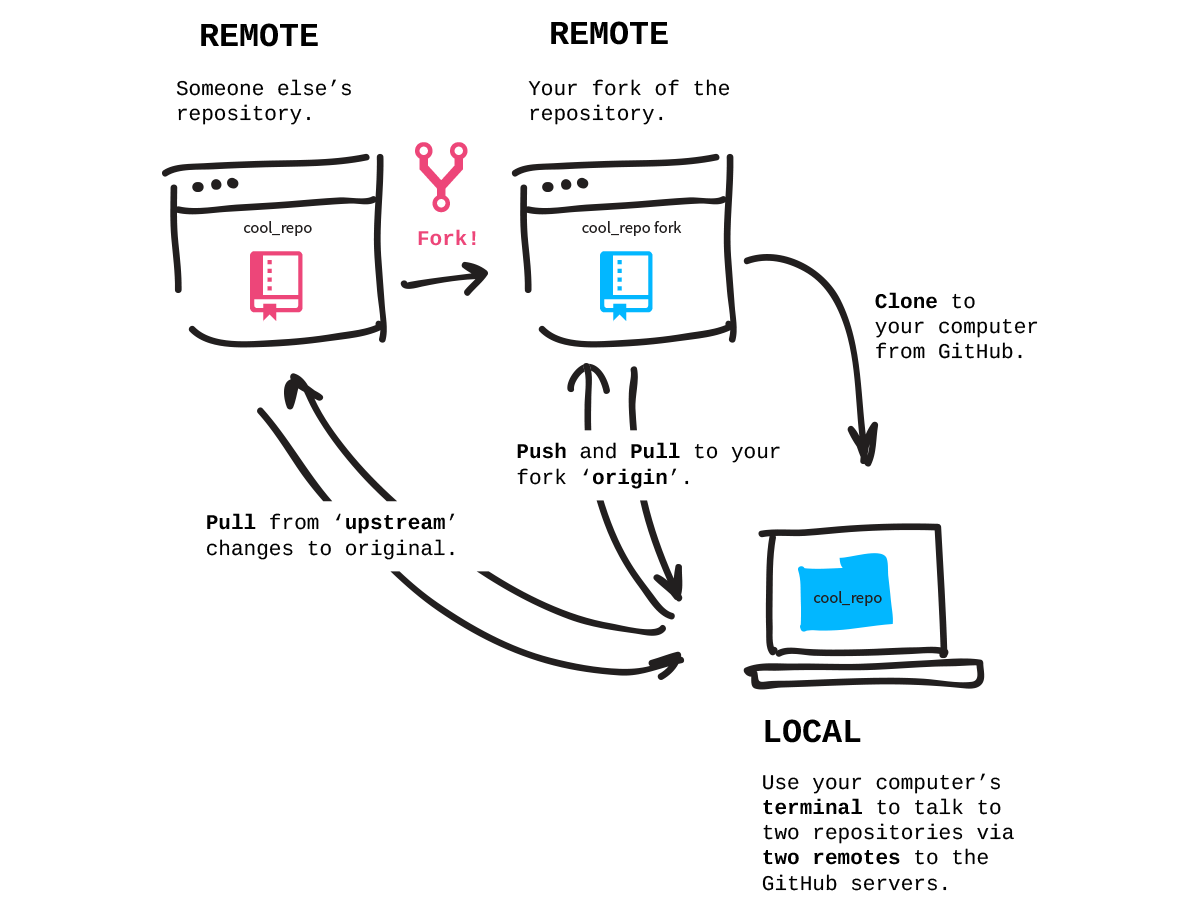

When you fork a repository, you're creating a copy of it on your GitHub account. Your fork begins its life as a remote repository. Forks are used for creating your own version of a project or contributing back fixes or features to the original project.

Once a project is forked, you then clone (aka copy) it from GitHub to your computer to work on locally.

The project we'll work with is http://github.com/jlord/patchwork. Go to that site and click the fork button at the top right. Once the fork animation is complete, you've got a copy on your account. Copy your fork's HTTP URL on the right sidebar.

Now, in terminal, clone the repository onto your computer. It will create a new folder for the repository so no need to create one. But make sure you aren't cloning it inside of another Git repository folder! So, if you're still inside of the 'hello-world' repository you worked in on the earlier challenges, back out of that folder. You can leave the folder you're in (and be in the folder that it was inside of) by 'changing directory' with two dots:

$ cd ..

Now clone: $ git clone <URLFROMGITHUB>

Go into the folder for the fork it created (in this case, named 'patchwork')

$ cd patchwork

Now you've got a copy of the repository on your computer and it is automatically connected to the remote repository (your forked copy) on your GitHub account.

But what if the original repository you forked from changes? You'll want to be able to pull in those changes too. So let's add another remote connection, this time to the original, http://github.com/jlord/patchwork, repository with its URL, found on the right hand side of the original on GitHub.

You can name this remote connection anything you want, but often people use 'upstream', let's use that for this.

$ git remote add upstream https://github.com/jlord/patchwork.git

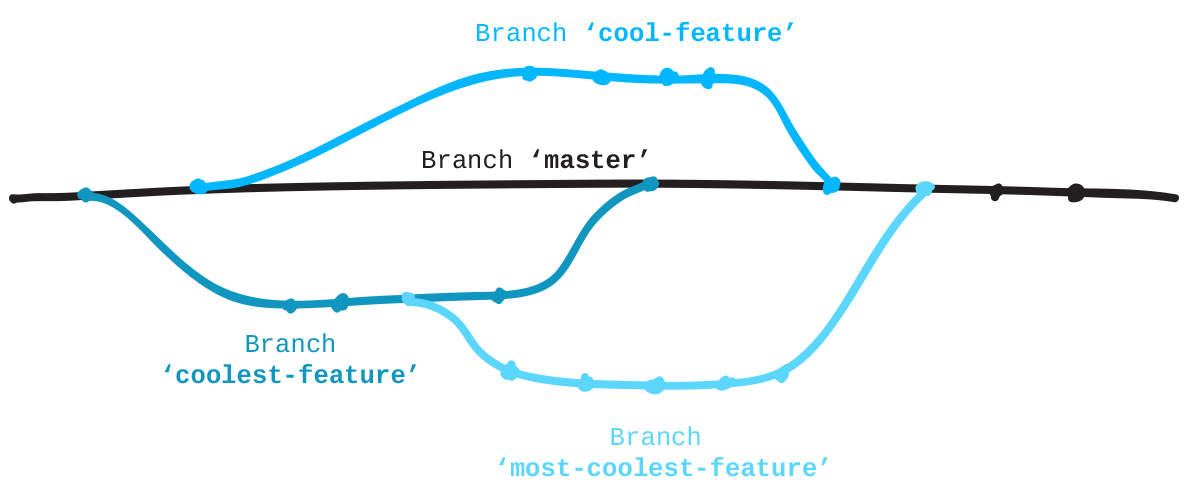

Git repositories use branches to isolate work when needed. It's common practice when working on a project or with others on a project to create a branch to keep your changes in until they are ready. This way you can do your work while the main, commonly named 'master', branch stays stable. When your branch is ready, you merge it back into 'master'.

For a great visualization on how branches work in a project, see this GitHub Guide: http://guides.github.com/overviews/flow/

GitHub will automatically serve and host static website files in branches named 'gh-pages'. Since the project you forked creates a website, its main branch is 'gh-pages' instead of 'master'. All sites like this can be found using this pattern for the URL:

http://githubusername.github.io/repositoryname

When you create a branch, Git copies everything from the current branch you're on and places it in the branch you've requested.

Type git status to see what branch you're currently on (it should be 'gh-pages').

Create a branch and name it "add-", where 'username' is your username. For instance, "add-jlord". Branches are case-sensitive so name your branch exactly the way your GitHub name appears.

$ git branch <BRANCHNAME>

Now you have a branch with a new name identical to 'gh-pages'.

To go into that branch and work on it, similar to using cd to change directory in terminal, you checkout a branch. Go onto your new branch:

$ git checkout <BRANCHNAME>

Back to the text editor:

- Create a new file named "add-.txt", where 'username' is your username. For instance, "add-jlord.txt".

- Then, just write your GitHub username in it, that's it and that's all. For instance, I'd type 'jlord'.

- Save this file in the 'contributors' folder in Patchwork: Patchwork/contributors/add-yourusername.txt

- Next, check in your changes!

Go through the steps for checking in a project:

$ git status

$ git add <FILENAME>

$ git commit -m "<commit message>"

Now push your update to your fork on GitHub:

$ git push origin <BRANCHNAME>

Collaborators are other GitHub users who are given permission to make edits to a repository owned by someone else. To add collaborators to a project, visit the repository's GitHub page and click the 'Settings' icon on the right side menu. Then select the 'Collaborators' tab. Type in the username to add and click 'Add'.

Go to your forked Patchwork repository's page on GitHub and add 'reporobot' as a collaborator. The URL should look like this, but with your username.

github.com/YOURUSERNAME/patchwork/settings/collaboration

If you're working on something with someone you need to stay up to date with the latest state. So you'll want to pull in any changes that may have been made.

Step: What has Reporobot been up to?

See if Reporobot has made any changes to your 'add-' branch by pulling in from the remote named 'origin' on GitHub:

$ git pull <REMOTENAME> <BRANCHNAME>

If nothing's changed, it will tell you 'Already up-to-date'. If there are changes, it will merge those changes into your local version.

When you make changes and improvements to a project you've forked, often you'll want to send those changes to the maintainer of the original and request that they pull the changes into the original so that everyone can benefit from the updates - that's a pull request.

We want to add you to the list of workshop finishers, so make a pull request to the original: https://github.com/jlord/patchwork

Visit the original repository you forked on GitHub, in this case http://github.com/jlord/patchwork.

Often GitHub will detect when you've pushed a branch to a fork, and display a 'Compare & pull request' button at the top of both the original and forked repositories. If you see this for your 'add-username' branch, you can click it to continue. If not:

- Go to your forked repository.

- Click 'Pull requests' on the right-side menu, then 'New pull request' at the top.

- Select the branch with the changes you want to submit. It should be the one with 'add-yourusername'.

- Click 'Create pull request' at the top.

You'll now see a page with the details of the pull request you're in the process of submitting. The page shows the commits and changes associated with your pull request as compared to the 'gh-pages' branch of the original.

If the original repository has a contribution documentation, GitHub will link to it. This is documentation from repository owners on how to best make contributions to that project.

If everything is good, and as you expect it:

- Click 'Create pull request'

- Add a title and description to the changes you're suggesting the original author pull in.

- Click 'Send pull request'!

If all is well with your pull request, it will be merged within moments. If it's not merged automatically within a few moments, you'll then likely have some comments from Reporobot on why it couldn't merge it. If so, close your pull request on GitHub, make the necessary changes to your branch, push those changes and resubmit your pull request.

Your pull request has been merged! Now, since you know that you definitely want those updates in your forked version, and your branch is in good working order, merge it into the main branch on your forked repository, in this case, 'gh-pages'.

First, move into the branch you want to merge into — in this case, branch 'gh-pages'.

$ git checkout gh-pages

Now tell Git what branch you want to merge in — in this case, your feature branch that begins with "add-".

$ git merge <BRANCHNAME>

Tidy up by deleting your feature branch now that it has been merged.

$ git branch -d <BRANCHNAME>

You can also delete the branch from your fork on GitHub:

$ git push <REMOTENAME> --delete <BRANCHNAME>

And last but not least, if you pull in updates from the original (since it now shows you on the home page) you'll be up to date and have a version too, live at: yourusername.github.io/patchwork.

To pull from the original upstream:

$ git pull upstream gh-pages

Thanks for visiting, if you like this please feel free to star my repo, follow me or even contact me about contributing as it will be a lot of work and having help would be cool.

- HTML5 and CSS

- Responsive Design with Bootstrap

- Gear up for Success

- jQuery

- Basic JavaScript

- Object Oriented and Functional Programming

- Basic Algorithm Scripting

- Basic Front End Development Projects

- Intermediate Algorithm Scripting

- JSON APIs and Ajax

- Intermediate Front End Development Projects

- Claim Your Front End Development Certificate

- Upper Intermediate Algorithm Scripting

- Automated Testing and Debugging

- Advanced Algorithm Scripting

- AngularJS (Legacy Material)

- Git

- Node.js and Express.js

- MongoDB

- API Projects

- Dynamic Web Applications

- Claim Your Back End Development Certificate

- Greefield Nonprofit Project 1

- Greefield Nonprofit Project 2

- Legacy Nonprofit Project 1

- Legacy Nonprofit Project 2

- Claim your Full Stack Development Certification

- Whiteboard Coding Interview Training

- Critical Thinking Interview Training

- Mock Interview 1

- Mock Interview 2

- Mock Interview 3