This will serve as a repository for my notes, both new and old, surrounding Computer Science fundamentals.

I want to improve my fundamental knowledge over the course of the next 6-12 months, rounding out any core Computer Science (see Task List below for specifics) related information I am lacking. This will be a long-term venture with plenty of notes, videos, articles, and of course code samples along the way. Most of the code within my notes will be Python, but I will likely blend in C-related languages in the future..

I am doing this for myself first and foremost, not anyone else.

"Learning is not attended by chance, it must be sought for with ardor and diligence." - Abigail Adams

- Fixed vs. Growth Mindset

- The blueprint I am basing this guide off

- Getting a Job at the Big 4 (sensational title, but solid talk)

Don't feel overwhelmed at the feeling that you have an exorbitant about of information to digest; there's way too much to know, and nobody knows everything.

- Low-level knowledge

- Operating Systems

- Data Structures

- Algorithms

- Object-Oriented Design

- System Design (solving problems at scale)

- Databases

- Web Apps & Servers

- Math

- Built-in Functions

High vs Low-level

High and low refer to the level of abstraction between the two languages; low having a low level of abstraction and high having a high level. Everything in programming is about abstraction to some degree.

- High-level language

- Python, C++, Java, etc.

- Easier to learn, abstracted from the machine, comes "batteries-included", access to tools like regex, databases, etc.

- Low-level language

- Machine language

- The process of encoding instructions in binary so that a computer can directly execute them.

- Assembly language

- Uses a slightly easier format to refer to the low level instructions (abstracts things a bit).

- Harder to learn, closer to the machine, requires a high level of skill to write programs efficiently.

- Machine language

Compiled vs Interpreted

In interpreted languages, the code is executed from top to bottom and the result of the running code is immediately returned. The code does not need to be transformed into a different form before it is run by the computer. * Both Python and JavaScript are interpreted.

On the other hand, in compiled languages the code is transformed (compiled) into another form before they are run by the computer. * Both C & C++ are compiled into assembly language.

Both approaches have advantages and disadvantages that I will touch on later.

Python

Python is an example of high-level, general purpose language (as opposed to a low-level language). It is a great language for both beginners and experts alike.

Object-oriented-programming allows for variables to be assigned at either the class (class variables) or instance level (instance variables).

Whenever we expect variables are going to be consistent across all of our instances, or whenever we would like to initialize a variable, we can define that variable at the class level. Conversely, whenever we expect the variables to change significantly across instances we should define them at the instance level.

Class variables are owned by the class and are thus shared with all instances of the class. In Python, we can think of this as the rough equivalent of a static variable in another language. See the below example of a class variable (typically placed below the class header and above the methods, constructor or otherwise):

class Dude:

guy = 'Cooper'

By creating an instance of the Dude class we can print the variable using dot notation:

new_dude = Dude()

print(new_dude.guy)

>>> Cooper

Class variables can consist of any data type, not just a string. Class variables allow us to define variables upon constructing the class. These variables and their associated values are then accessible to each instance of the class.

Unlike class variables, instance variables are owned by the instances of the class. Why is this important? Well, each object or instance of the class will have different instance variables. Instance variables are defined in methods (functions). See the below example:

class Dude:

def __init__(self, guy):

self.guy = 'Cooper'

Whenever we create the above object we have to explicitly define the variables, which are passed in as parameters within the method. We can print the example in a similar dot notation fashion:

class Dude:

def __init__(self, guy):

self.guy = guy

new_dude = Dude('Cooper')

print(new_dude.guy)

>>> Cooper

As you can see, the output is not 'global' so to speak, and is instead made up of the values that we initialize for the object instance of Dude.

Because they are owned by the objects of a class, instance variables allow for each object or instance to have different values assigned to those variables. You can see how this can aid immensely when writing code that we can re-use and that is modular.

It can be common to encounter a combination of the above variables, so let's take a look at an example that extends the Dude class we used above in further detail:

class Dude:

# Class variables

guy = 'Cooper'

location = 'Austin'

# Constructor method with instance variables age

def __init__(self, topic):

self.topic = topic

# Method with instance variable breaks

def set_breaks(self, breaks):

print("This user has " + str(breaks) + " breaks")

def main():

# First object, set up instance variables of constructor method

compsci = Dude("Computer Science")

# Print out instance variable age

print(compsci.topic)

# Print out class variable location

print(compsci.location)

# Use set_breaks method and pass breaks instance variable

compsci.set_breaks(5)

# Print out class variable guy

print(compsci.guy)

# Blank space

print()

# First object, set up instance variables of constructor method

it = Dude("IT")

# Print out instance variable age

print(it.topic)

# Print out class variable location

print(it.location)

# Use set_breaks method and pass breaks instance variable

it.set_breaks(10)

# Print out class variable guy

print(it.guy)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

After running the program we will see the following results returned to us:

>>> Computer Science

>>> Austin

>>> This user has 5 breaks

>>> Cooper

>>> IT

>>> Austin

>>> This user has 10 breaks

>>> Cooper

In the above example we have made use of both class and instance variables within the Dude class, compsci and it.

In object-oriented-programming, there are two types of variables when dealing with classes:

- Class variables

- Objects at the class level ("global within a class").

- Instance variables

- Objects at the object level.

This differentiation allows us to use class variables to initialize objects with a specific value assigned to variables, and use different variables for each object with instance variables.

Making use of class- and instance-specific variables can ensure that our code adheres to the DRY principle to reduce repetition within code.

JavaScript

The JavaScript ecosystem has been and is continuing to grow at breakneck speeds. New libraries (shiny objects) are coming out all the time and, as a result, I believe the time has never been better to learn the fundamentals of how the language operates.

One quick tidbit to remember: don't feel pressured to use a framework if you don't have a need for it. GitHub removed jQuery earlier this year and runs on vanilla JavaScript , and HackerNews contains only 150 lines of un-minified JavaScript (yes, in total). Your site will run blazingly fast and be less error prone if you do not over-engineer your requirements through a batteries-included framework (Vue, React, Angular, etc.)

Dan Abramov (co-founder of Redux) has even made a post about this exact issue, stating that sometimes their tool isn't the right one for the job.

-

Javascript is a versatile language and used in both programming paradigms, functional and object-oriented.

-

JavaScript code can be executed both in the browser (front-end) and the server (back-end).

-

JavaScript manipulates HTML elements (animations, etc) by accessing the DOM.

-

ES (ECMAScript) is actually the blueprint convention that JavaScript is based on, and it was created to standardize JavaScript source.

-

In JavaScript you can increment by using

variable++and decrement withvariable--. This will return the current value and then increment it afterwords. If we want to the variable before returning it, we simply have to denote the increments and decrements in the reverse fashion:++variableand--variable, respectively. -

The primary package manager is

npm(akin topip). -

Babel converts your JavaScript into EMCAScript 2015 syntax and beyond.

-

Don't use inline JavaScript, and always add event listeners if you need this type of functionality:

// won't run until the event, which in this case is the HTML // being loaded, has been fired document.addEventListener("DOMContentLoaded", function() { ... }); -

The more modern way to do this is to use the

asyncattribute (only works for external scripts), which tells the browser to continue downloading the HTML content once the<script>tag element has been reached. This replaces the previous method of placing JavaScript at the bottom of the body tag as well (which can cause serious performance issues for sites with a large amount of JavaScript).<script src="script.js" async></script>Async and Defer

Two ways we can bypass the problem of the blocking script,

async&defer.-

async- Asynchronous (

async) scripts will download the script without blocking the rendering on the page and will execute as soon as the script finishes downloading. This does not guarantee the order in which the scripts execute, only that it will not stop the rest of the page from loading. Thus, it is best to useasyncwhen the external scripts will run independently from each other and depend on no other script from the page.

- Asynchronous (

-

defer- When we need to run the scripts in the order they appear in the page, we can use

defer:

<script defer src="js/script1.js"></script> <script defer src="js/script2.js"></script> - When we need to run the scripts in the order they appear in the page, we can use

To summarize, if your scripts can run independently without dependencies, use

async. Otherwise, if the order of the scripts matters, we can utilizedefer.Let and Const

Two ways we can store the data we use is through "containers" such as

letandconst.-

let- If you expect your variable to change, you would utilize the

letidentifier.

let randomNumber = Math.floor(Math.random() * 100) + 1; ... let guessCount = 1; let resetButton; - If you expect your variable to change, you would utilize the

-

const- If you don't expect your variable to change or simply need to to stay constant, you would utilize the

constidentifier:

const guesses = document.querySelector('.guesses'); const lastResult = document.querySelector('.lastResult'); const lowOrHi = document.querySelector('.lowOrHi'); const guessSubmit = document.querySelector('.guessSubmit'); const guessField = document.querySelector('.guessField'); - If you don't expect your variable to change or simply need to to stay constant, you would utilize the

In our case, we are using constants to store references to parts of our user interface; the text inside some of them might change, but the HTML elements referenced stay the same.

Switch statements

While

if...elsestatements can be useful for the majority of cases, there are some instances where you just want to set a variable to a value or print out said value, and for this theif...elseprocess can be overly cumbersome.Enter

switchstatements, which take a single expression/value as an input and then look through a number of choices until they find one that matches the value, executing the corresponding code that goes along with it.switch (expression) { case choice1: run this code break; case choice2: run this code instead break; // include as many cases as you like default: actually, just run this code }Function scopes and conflicts

Whenever you create a functions and declare variables within it, those variables and other things defined within the function are inside their own seperate **scope**. What does that mean? They are locked away in their own seperate compartments, unreachable from inside other functions or from code outside of the function.The top level outside of your functions is referred to as the global scope, which means that values are accessible from anywhere in the code.

Think of how a Zoo is setup. Each animal has their own cut-off section, or a function scope, and the Zoo Keeper has they keys to every section, or a global scope.

Common DOM API Functions

document.querySelector()- The Document method

querySelector()returns the first Element within the document that matches the specified selector, or group of selectors. If no matches are found, null is returned.- Depth-first preorder traversal starting with the first node and descending down through the children.

- Examples:

- Finding the first element in the document with the class

.myclass.

let el = document.querySelector(".myclass");- Selectors can also be really powerful, as demonstrated in the following example. Here, the first

<input>element with the name "login" (<input name="login"/>) located inside a<div>whose class is "user-panel main" (<div class="user-panel main">) in the document is returned:

let el = document.querySelector("div.user-panel.main input[name='login']"); - Finding the first element in the document with the class

- The Document method

document.querySelectorAll()- The Element method

querySelectorAll()returns a static (not live) NodeList representing a list of the document's elements that match the specified group of selectors. - Examples:

- To obtain a NodeList of all of the

<p>elements in the document:

let matches = document.querySelectorAll("p");- This example returns a list of all

<div>elements within the document with a class of either"note"or"alert":

let matches = document.querySelectorAll("div.note, div.alert");- Here, we get a list of

<p>elements whose immediate parent element is a div with the class"highlighted"and which are located inside a container whose ID is"test".

let container = document.querySelector("#test"); let matches = container.querySelectorAll("div.highlighted > p"); - To obtain a NodeList of all of the

- The Element method

<value>.setAttribute()- We can use

<value>.setAttribute()when we need to update the attributes of an element in the document. - Examples:

- Updates the

nameattribute and changes the value to 'helloButton', and afterwords sets the"disabled"attribute toTrue, which results in our button being disabled.

<button>Hello World</button> let b = document.querySelector("button"); b.setAttribute("name", "helloButton"); b.setAttribute("disabled", ""); - Updates the

- We can use

<node>.onclick()- The

<node>.onclickevent is raised when the user clicks on an element. The click event will occur after themousedownandmouseupevents.- This sets up a

clickevent listener for our element which will print out a result when clicked.

closeBtn.onclick = function() { console.log('success!'); }- This declares a

btnvariable that selects our button and stores it in a reference, and then calls a function afterwards.

var btn = document.querySelector('button'); btn.onclick = function i(); - This sets up a

- The

document.createElement()- In an HTML document, the

document.createElement()method creates the HTML element specified by tagName, or an HTMLUnknownElement if tagName isn't recognized. - Examples:

- This creates a new

<div>and inserts it into the HTML body.

let newDiv = document.createElement("div"); - This creates a new

- In an HTML document, the

document.createTextNode()document.createTextNode()is used to insert a string into a specific, pre-defined node.- Examples:

- This inserts a string into the node as text content.

let newContent = document.createTextNode("Hi there and greetings!");

<node>.textContent()- If we wish to populate the text contents of a node, we can utilize the

<node>.textContent()module.- Inserts the newly created element into the DOM before our first value (

<div>).

let msg = document.createElement('p'); msg.textContent = 'This is a message box'; newDiv.appendChild(msg); - Inserts the newly created element into the DOM before our first value (

- If we wish to populate the text contents of a node, we can utilize the

<node>.appendChild()<node>.appendChild()is used when we need to add (append) our node to a previously created element (<div>in this case).- Examples:

- This adds the text node to our previously created

<div>.

newDiv.appendChild(newContent); - This adds the text node to our previously created

document.getElementById()- In an HTML document,

document.getElementById()is used when we need to select an element by itsidvalue. - Examples:

- Selects the element

<div1>from the document.

let currentDiv = document.getElementById("div1"); - Selects the element

- In an HTML document,

document.body.insertBefore()- Finally, we can use

document.body.insertBefore()to insert the newly created element and its conents into the DOM. - Examples:

- Inserts the newly created element into the DOM before our first value (

<div>).

document.body.insertBefore(newDiv, currentDiv); - Inserts the newly created element into the DOM before our first value (

- Finally, we can use

Promises

A

promiseis an object representing the eventual completion or failure of an asynchronous operation. You can both consume and create promises.Essentially, a

promiseis a returned object to which you attach callbacks, instead of passing callbacks into a function.Basic Example

Let's look at the most basic example of a promise before diving any further. A

promisehas a callback function that has two arguments,resolveandreject. As you would expect,resolveis executed when thepromisehas been fulfilled and completely successfully. On the other hand,rejectis used for when the promise has failed to complete successfully (whether due to time constraints, logic, or something else).// assign our new promise to the variable `promiseToCleanTheRoom` let promiseToCleanTheRoom = new Promise(function(resolve, reject) { // cleaning the room function // set our indicator to `true` after we have cleaned the room, // or `false` to trigger out `reject` callback. let isClean = false; // if the indicator exists, then execute our `resolve` callback function, otherwise return our `reject` function. if (isClean){ resolve('clean'); // return the status back from the `resolve` function } else { reject('not clean'); } }); // only executed once the `promise` has resolved promiseToCleanTheRoom.then(function(fromResolve){ console.log('the room is ' + fromResolve); // only executed once the `promise` was rejecteed }).catch(function(fromReject){ console.log('the room is ' + fromReject) });Intermediate Example

Let's look at a more complex example. Say for instance we had three promises,

cleanRoom,removeGarbageandwinIceCreamthat were supposed to be executed sequentially (chained).We could implement this in the following manner:

let cleanRoom = function() { return new Promise(function(resolve, reject) { resolve('cleaned the room'); }); }; let removeGarbage = function(p) { return new Promise(function(resolve, reject) { resolve('removed garbage'); }); }; let winIceCream = function(p) { return new Promise(function(resolve, reject) { resolve('won ice-cream'); }); }; // now we are essentially creating a `promise` chain. once `cleanRoom` resolves, we will execute a callback and return another `promise`, `removeGarbase`. Which will chain into another returned callback `promise` `winIceCream`, which will finally callback one more promise and log that we are completed with the chain. cleanRoom().then(function() { return removeGarbage(); }).then(function(){ return winIceCream(); }).then(function() { console.log('well done, everything is done!') }); >>> well done, everything is done!If we wanted to instead pass through a

messageargument and print out the results at the end, we could make the following adjusments:let cleanRoom = function() { return new Promise(function(resolve, reject) { resolve('cleaned the room'); }); }; let removeGarbage = function(message) { return new Promise(function(resolve, reject) { resolve(message + ', removed garbage'); }); }; let winIceCream = function(message) { return new Promise(function(resolve, reject) { resolve(message + ', won ice-cream'); }); }; // now we are essentially creating a `promise` chain. once `cleanRoom` resolves, we will execute a callback and return another `promise`, `removeGarbase`. Which will chain into another returned callback `promise` `winIceCream`, which will finally callback one more promise and log that we are completed with the chain. cleanRoom().then(function(result) { return removeGarbage(result); }).then(function(result){ return winIceCream(result); }).then(function(result) { console.log('well done, everything is done!' + result) }); >>> well done, everything is done! cleaned the room, removed garbage, won ice-creamThis is useful if we need to pass values through our

promisechain and maintain state.Right now, all of the above examples are executing our promises sequentially, one after another, and not in parallel. What if we instead wanted to have our promises spawn at the same time and once all of them are completeted to execute a final function (be careful about race conditions)?

We can utilize the

.all()keyword to be able to pass in an array of promises and then attach a single.then()callback function to execute once each promise has been resolved:Promise.all([cleanRoom(), removeGarbage(), winIceCream()]).then(function() { console.log('all three promises have been finished') });What about if we just wanted to execute a callback function once any of the promises have finished executing? We can utilize the

.race()keyword instead of.all()to denote this change:Promise.race([cleanRoom(), removeGarbage(), winIceCream()]).then(function() { console.log('one promise is finished.') });Intermediate Example #2

Let's say we were to create a function,

createAudioFileAsync(), which asynchronously generates a sound file given a configuration record and two callback functions, one called if the audio file is successfully created, and the other called if an error occurs.Now, Let's look at some of the code that uses

createAudioFileAsync()function successCallback(result) { console.log("Audio file ready at URL: " + result); } function failureCallback(error) { console.log("Error generating audio file: " + error); } createAudioFileAsync(audioSettings, successCallback, failureCallback);This is quite verbose and we can simply it to a single line, as modern functions return a

promisethat we can attach directly to our callback instead.If

createAudioFileAsync()was created to return apromiseinstead, we could use the following block of code:createAudioFileAsync(audioSettings).then(successCallback, failureCallback); # the above is short for the below code const promise = createAudioFileAsync(audioSettings); promise.then(successCallback, failureCallback);This is what is referred to as an asynchronous function call, and it is extremely common and has several advantages that are touched on below.

Unlike old-style passed-in callbacks, a

promisecomes with some guarantees:- Callbacks will never be called before the completion of the current run of the JavaScript event loop.

- Callbacks added with

then()even after the success or failure of the asynchronous operation, will be called, as above. - Multiple callbacks may be added by calling

then()several times. Each callback is executed one after another, in the order in which they were inserted.

One of the great things about using promises is chaining.

A common need is to execute two or more asynchronous operations back to back, where each subsequent operation starts when the previous operation succeeds, with the result from the previous step. We accomplish this by creating a

promisechain.The magic? The

then()function returns a newpromise, different from the original:const promise = doSomething(); const promise2 = promise.then(successCallback, failureCallback); or const promise2 = doSomething().then(successCallback, failureCallback);This second

promise(promise2) represents the completion not just ofdoSomething(), but also ofsuccessCallbackandfailureCallback, which can be other asynchronous functions returning apromise. When that's the case, any callbacks added topromise2get queued behind thepromisereturned by eithersuccessCallbackorfailureCallback.Basically, each promise represents the completion of another asynchronous step in the chain.

In the old days, doing several asynchronous operations in a row would lead to the classic callback pyramid of doom:

``` doSomething(function(result) { doSomethingElse(result, function(newResult) { doThirdThing(newResult, function(finalResult) { console.log('Got the final result: ' + finalResult); }, failureCallback); }, failureCallback); }, failureCallback); ```With modern functions, we attach our callbacks to the returned promises instead, forming a promise chain:

``` doSomething().then(function(result) { return doSomethingElse(result); }) .then(function(newResult) { return doThirdThing(newResult); }) .then(function(finalResult) { console.log('Got the final result: ' + finalResult); }) .catch(failureCallback); ```The arguments to

thenare optional, andcatch(failureCallback)is short forthen(null, failureCallback). You might see this expressed with arrow functions instead:``` doSomething() .then(result => doSomethingElse(result)) .then(newResult => doThirdThing(newResult)) .then(finalResult => { console.log(`Got the final result: ${finalResult}`); }) .catch(failureCallback); ```Important: Always return results, otherwise callbacks won't catch the result of a previous promise (with arrow functions

() => xis short for() => { return x; }).It's possible to chain after a failure, i.e. a

catch, which is useful to accomplish new actions even after an action failed in the chain. Read the following example:new Promise((resolve, reject) => { console.log('Initial'); resolve(); }) .then(() => { throw new Error('Something failed'); console.log('Do this'); }) .catch(() => { console.log('Do that'); }) .then(() => { console.log('Do this, no matter what happened before'); }); >>> Initial >>> Do that >>> Do this, no matter what happened beforeAs we can see, the text

Do thisis not displayed because theSomething failederror caused a rejection.A

promisechain will stop if it hits an exception, looking down the chain forcatchhandlers instead. This is similar to how synchronous code works:try { const result = syncDoSomething(); const newResult = syncDoSomethingElse(result); const finalResult = syncDoThirdThing(newResult); console.log(`Got the final result: ${finalResult}`); } catch(error) { failureCallback(error); }This symmetry with asynchronous code culminates in the async/await syntactic sugar in ECMAScript 2017:

async function foo() { try { const result = await doSomething(); const newResult = await doSomethingElse(result); const finalResult = await doThirdThing(newResult); console.log(`Got the final result: ${finalResult}`); } catch(error) { failureCallback(error); } }It builds on promises, e.g.

doSomething()is the same function as before.Promises solve a fundamental flaw with the callback pyramid of doom, by catching all errors, even thrown exceptions and programming errors. This is essential for functional composition of asynchronous operations.

Clojures

Any function where you are using a variable from outside of the scope is actually a closure. Closures are nothing but functions with preserved data.

Usually when you create a function in most programming languages you need to pass in some paramaters (arguments) or you define some inner variables. Let's look at a few basic examples below.

Basic Example

The following is a very simple function that takes in an argument, adds 2 to it, and returns the new value:let addTo = function (passed) { let inner = 2; return passed + inner; }; console.log(addTo(3)) >>> 5Interestingly enough, in JavaScript you can actually access the variable withing passing in an argument. How? By assigning it as a

globalvariable. Let's look at another example below:const passed = 3; let addTo = function (passed) { let inner = 2; return passed + inner; }; console.log(addTo()) >>> 5So, what does this have to do with closures? It may not look like it, but the above example is actually a very simple

closure. JavaScript uses something called lexical scoping. What this means is that the variableinneris not available outside of the function scope, wheraes everything that isglobalis available anywhere in the code (including inside the function).Let's take a look at the meta data surrounding our simple

addTo()function:console.dir(addTo) >>>If we run the following command and check the returned values (using Chrome Dev Tools or something of the like), we can see that under the functions

scopethere is aclosurethat containes our variabledpassedwith an assigned value of 3. This is how our above functionaddTo()utilizes closures to properly execute it's function. First it would check the functions' scope for the variable, if it cannot find it it will keep moving up the code until it does (and in this case it finds it globally). If it cannot find it, it will be undefined.This was a very simple example of a

clojureand not particularly useful outside of understand how clojures work, so let's look at a more complex example below.Basic Example #2

This is similar to our above example but we have broken it down into two functions,

addTo()andadd().let addTo = function(passed) { let add = function(inner) { return passed + inner }; return add; }; let addThree = new addTo(3); let addFour = new addTo(4); // returns a clojure of 3 and 4, respectively console.dir(addThree) >>> 3 console.dir(addFour) >>> 4 // we can easily create new functions and manipulate the results console.log(addThree(1)); >>> 4 console.log(addFour(1)); >>> 5Within the

addTo()function, we have another function calledaddthat will return the sum of the inheritedpassedargument and the passed ininnerargument. Afteradd()exectues,addTo()finally returnsadd(), which is our value (passed+inner).What this means is that we can create an unlimited amount of functions;

addToHundred,addToMillion, etc. Closures keep the variable that is needed to execute (3inaddThree, and4inaddFour) and it preserves this variable inside the function as a property (closure). When you execute each successive function, likeaddThree, it uses thatclosureto do the calculations.Working with npm

- Installing as a production dependency (

--save)npm install --save express moment ...

- Installing as a development-only dependency (

--save-dev)$ npm install --save-dev babel-cli babel-preset-env babel-watch ...

- All source code gets downloaded to the newly created

node_modulesfolder.

Working with Babel

-

When converting your JavaScript to ES5 (so that the node can understand it) using Babel, you will first need to establish a

.babelrcfile.{ "presets": ["env"] } -

Afterwards, you will need to add the following inside your

package.jsonfile, under the scripts section:"build": "babel server.js --out-dir build"{ "name": "node_express_tutorial", "version": "1.0.0", "description": "node express tutorial", "main": "index.js", "scripts": { "test": "echo \"Error: no test specified\" && exit 1", "build": "babel server.js --out-dir build" }, ################# # existing code # ################# } -

Finally, you will be able to run

npm build. Afterwards execute the following command (from inside the build folder):node build/server.jsin order to run your server succesfully. -

If you want to make any changes to the server, it will currently need to be re-built and restarted before any changes go live. In order to "hot-reload" our application, we can utilize babel-watch. Under the script section in our

package.jsonlet's add"dev-start": "babel-watch server.js"to ourpackage.json. -

We can now use

npm run dev-startto hot-reload and quickly test changes, without having to re-build our application every time.

Working with package.json

Interview Questions

- What is the difference between var and let?

varhas been around in JavaScript for a very long time, andletis pretty much its successor that has only been released in the past few years.lethas block scope, andvarhas function scope.

- What is the difference between let and const?

constis used whenever you need to assign something to a variable that you do not want to change. This doesn't mean it's immutable, as you can stillpushandpoparrays for instance, but it does mean that you can't assign a variable name that has already been previously defined.

- What is the difference between == and ===?

- When you use

==you are only comparing the value and not it's underlying type, whereas with===you are doing a deeper check that also compares the variables types.

5 == '5' # True 5 === '5' # False - When you use

- What is the use of an arrow function? *

- What is prototypal inheritance?

- Every object has a property

prototypewhere you can add methods and properties to it, and when you create new objects from these objects, the newly created objects will automatically inherit the property of the parent. - When you call an object it first looks at it's own properties to see if it is there, if it finds it it will execute. If it doesn't find it looks towards its parents' properties.

let car = function(model) { this.model = model; }; car.prototype.getModel = function() { return this.model; } let toyota = new car('toyota'); console.log(toyota.getModel()); - Every object has a property

- What is the difference between function declaration & function expression?

- A function declaration is equivalent to when you normally create a named function that is not assigned to any variable.

- A function expression is when you assign a function to a variable; akin to a lambda expression (anonymous function). This also changes the function to a variable scope. This is especially useful when we need to pass a function into another function by utilizing a variable argument.

# funcD(); function funcD() { console.log('function declaration'); }; # funcE(); let funcE = function() { console.log('function expression') }; - What are promises and why do we use them?

- Let's say we wanted to make an

ajaxcall that has to wait until something happens before executing. Once that thing happens and comes back, we execute our callback function (which can include anotherajaxcall, and so on and so forth). This is referred to as callback hell.

$.ajax({ url: "a.json", success: function(r { $.ajax({ url: "b.json?" + r.a, success: function(result) { $("#div1").html(result); } }); }) }); let p1 = new Promise(function(resolve, reject) { resolve($.ajax('a.json');) }); p1.then(function(r) { return new Promise() }).then(function(result) { $("#div1").html(result); }) - Let's say we wanted to make an

- Using setTimeout()?

setTimeoutturns the method call into anasycaction, therefore making it wait for every normal call in the stack before it can execute.

setTimeout(function() { console.log('a'); }) console.log('b') console.log('c') >>> 'b' >>> 'c' >>> 'a' - What is a closure and how do you use it?

- When a function returns another function, the returning function would hold all of it's environment in a class.

let obj = function() { let i = 0 # private variable return { setI(k) { i = k; }, getI() { return i; } } }; let x = obj(); x.setI(2); x.setI(3); console.log(x.getI()); >>> 3- If we were to look into the objects scope, we would see the closure property with the assigned value of 3.

-

SQL

-

Specify

JOINconditions- Why? If your query is complex, the

JOINconditions remain withJOINstatement. In the first example below, imagine if there were 15 other joined tables and theWHEREclause had 30 other criteria in it, it would quickly become difficult to work out what's going on. - source

# bad SELECT * FROM employee e, department d WHERE e.department_id = d.id ...# good SELECT * FROM employee e INNER JOIN department d ON e.department_id = d.id ... - Why? If your query is complex, the

Algorithm

"If problem solving is a central part of computer science, then the solutions that you create through the problem solving process are also important. In computer science, we refer to these solutions as algorithms. An algorithm is a step by step list of instructions that if followed exactly will solve the problem under consideration.

Our goal in computer science is to take a problem and develop an algorithm that can serve as a general solution. Once we have such a solution, we can use our computer to automate the execution. As noted above, programming is a skill that allows a computer scientist to take an algorithm and represent it in a notation (a program) that can be followed by a computer. These programs are written in programming languages." - source

Lambda

In computer programming, an anonymous function (or lambda expression) is a function that has no identifier (source).

-

Usually not more than a single line in length.

-

Can't contain more than one expression.

-

Lets check out an example:

The function version: def multiply(x, y): return x * yThis verison is too small, so let's convert it to a lambda. To create a lambda function, first denote the keyword

lambdafollowed by one of more arguments separated by comma and followed by colon sign ( : ), which is then followed by a single line expression. See below:The lambda version: r = lambda x, y: x * y r(12, 3) # call the lambda function >>> 36We can even call the lambda function without assigning it to a variable:

(lambda x, y: x * y)(12, 3) >>> 36

-

Recursion

A recursive function is essentially just a function that will continue to call itself until it some condition is met to return a result (source).

Let's say we wanted to recursively calculate n! (factorial) in Python:

def factorial_recursive(n):

# Base case: 1! = 1

if n == 1:

return 1

# Recursive case: n! = n * (n-1)!

else:

return n * factorial_recursive(n-1) # recursively call function while subtracting 1 from n each time (will continue until we reach 0)

>>> 120

# adding stack frame to call stack

# factorial_recursive(1)

# factorial_recursive(2)

# factorial_recursive(3)

# factorial_recursive(4)

# factorial_recursive(5)

# 5*4*3*2*1

# unwinding call stack

# 1 * 2

# 2 * 3

# 6 * 4

# 24 * 5

# hit end of call stack, returns 120

Each recursive call will add a stack frame to the call stack until we reach the base case. Then, the stack begins to unwind as each call returns the result (as you can see in the above example, or a much better one on this page).

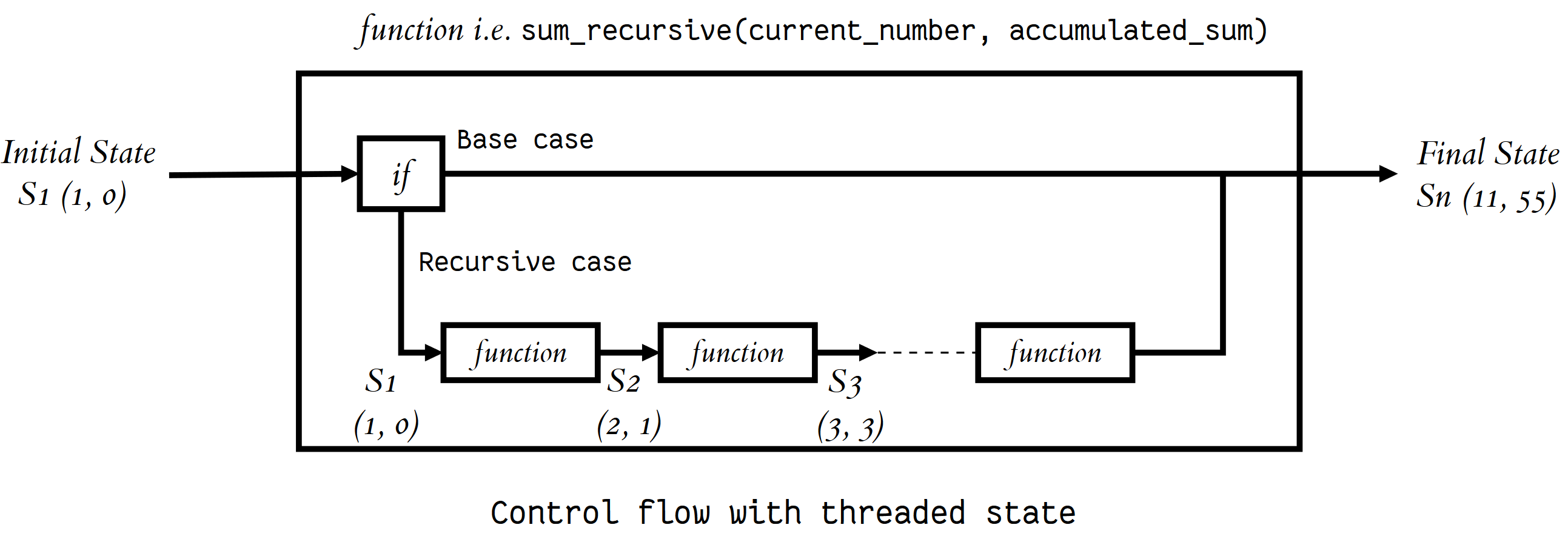

Each recursive call contains its own execution context, so in order to maintain state we need to do a few things:

- Thread the state through each recursive call so that the current state is part of the current call's execution content.

- Keep the state in a global scope.

Let's say we had to calculate 1+2+3...+10 using recursion. We need to maintain the state -- the current number we are adding & the accumulate sum until now.

Let's look at an example where we pass (thread) the updated current state to each recursive call as arguments:

def sum_recursive(current_number, accumulated_sum):

# return the final state

if current_number == 11: # base case

return accumulated_sum

# recursive case

# thread the state through the recursive call

else:

return sum_recursive(current_number + 1, accumulated_sum + current_number)

print(sum_recursive(1, 0))

>>> 55

and similarly, here's how you would maintain by utilizing a global scope:

# global mutable state

current_number = 1

accumulated_sum = 0

def sum_recursive_global():

global current_number

global accumulated_sum

if current_number == 11: # base case

return accumulated_sum

# recursive case

else:

accumulated_sum = accumulated_sum + current_number

current_number = current_number + 1

return sum_recursive_global()

print(sum_recursive_global())

>>> 55

In general, threading will keep your code much cleaner, less bug prone and more maintainable for others.

A data structure is defined as recursive if it can be defined in smaller terms of a smaller version of itself. One example is a list, as explained below.

If we were to start with an empty list and were only able to perform the following operation...

# return a new list that is the result of

# adding element to the head (i.e. front) of input_list

def attach_head(element, input_list):

return [element] + input_list

...we could use the attach_head function to generate any list of any size. For example, if we wanted to return the list [1, 46, -31, 'hello']:

attach_head(1, attach_head(46, attach_head(-31, attach_head("hello", []))))

# unwinding the call stack

# ['hello']

# [-31, 'hello']

# [46, -31, 'hello']

# [1, 46, -31, 'hello']

We can also perform the following recursive implementations with other data structures like sets, trees, dictionaries and more.

These recursive data functions and recursive data structures balance each-other perfectly; like yin and yang.

The recursive function’s structure can often be modeled after the definition of the recursive data structure it takes as an input. Let's see how the writer implemented this example of calculating the sum of all lists recursively:

def list_sum_recursive(input_list):

# base case

if input_list == []:

return 0

# recursive case

# decompose the original problem into simpler instances of the same problem

# by making use of the fact that the input is a recursive data structure

# and can be defined in terms of a smaller version of itself

else:

head = input_list[0]

smaller_list = input_list[1:]

return head + list_sum_recursive(smaller_list)

print(list_sum_recursive([1,2,3]))

>>> 6

Let's look at an example for creating a function to calculate the nth Fibonacci number:

def fibonacci_recursive(n):

print("Calculating F", "(", n, ")", sep="", end=", ")

# base case

if n == 0:

return 0

elif n == 1:

return 1

# becursive case

else:

return fibonacci_recursive(n-1) + fibonacci_recursive(n-2)

fibonnaci_recursive(5)

>>> Calculating F(5), Calculating F(4), Calculating F(3), Calculating F(2), Calculating F(1), Calculating F(0), Calculating F(1), Calculating F(2), Calculating F(1), Calculating F(0), Calculating F(3), Calculating F(2), Calculating F(1), Calculating F(0), Calculating F(1), 5

As we can see in the above example, we are unnecessarily recomputing values. Let's try to improve this function by caching the results of each computation:

from functools import lru_cache

@lru_cache(maxsize=None)

def fibonacci_recursive_cache(n):

print("Calculating F", "(", n, ")", sep="", end=", ")

# base case

if n < 2:

return n

# recursive case

else:

return fibonacci_recursive_cache(n-1) + fibonacci_recursive_cache(n-2)

print(fibonacci_recursive_cache(5))

>>> 5

More about memoization and caching here, but lru essentially stands for least-recently-used and it is a FIFO approach to managing the size of a cache. Fundamentally, this is the same as manually incorporating a memoize function but instead allows you to just import it and wrap your function in the respective decorator.

The only thing to keep is mind is that lru_cache utilizes a dictionary to cache results, so positional and keyword arguments (keys) to the function must be hashable.

Python doesn't have built-in support for a tail-call elimination. This means you can cause a stack overflow if you end up adding more stack frames than the default call stack depth:

import sys

sys.getrecursionlimit()

>>> 3000

This limitation is important to keep in mind if you are working with a program that requires deep recursion.

Iterator

In the simplest terms, an iterator is simply an object that you can iterate ("reiterate") over, or more specifically an object that will return data one element at a time. Iterators are elegantly tucked away behind the scenes and are absolutely everywhere in Python; for loops, list comprehensions, generators and more.

Technically speaking, Python iterator objects must implement two special methods, __iter__() and __next__(), which collectively make up what is referred to as the iterator protocol.

Most of built-in containers in Python like lists, tuples, strings and more are iterables. The iter() function (which in turn calls the __iter__() method) returns an iterator from them.

# define a list

my_list = [4, 7, 0, 3]

# get an iterator using iter()

my_iter = iter(my_list)

## iterate over it using next()

print(next(my_iter))

>>> 4

print(next(my_iter))

>>> 7

## next(obj) is same as obj.__next__()

print(my_iter.__next__())

>>> 0

print(my_iter.__next__())

>>> 3

## This will raise error, no items left

next(my_iter)

>>> Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

StopIteration

What's much more likely to see than the above is automatically iterating using a for loop. As long as the object is an iterator, we can seamlessly use this loop to iterate over it:

my_list = [4, 7, 0, 3]

for element in my_list:

print(element)

>>> 4

>>> 7

>>> 0

>>> 3

How is the for loop actually implemented? Good question, check out the code below:

for element in iterable:

# do something with element

-----------------------------------------------------

# create an iterator object from that iterable

iter_obj = iter(iterable)

# infinite loop

while True:

try:

# get the next item

element = next(iter_obj)

# do something with element

except StopIteration:

# if StopIteration is raised, break from loop

break

Internally, the for loop creates an iterator object iter_obj by calling iter() on the iterable.

Ironically, this for loop is actually an infinite while loop.

Inside the loop, it calls next() to get the next element and executes the body of the for loop with this value. After hitting the last item in the iterable, StopIteration is raised, which is internally caught and thus ends the loop.

In theory, there can be infinite iterators which would lead to an infinite loop.

The built-in function iter() can be called with two arguments, where the first argument must be a callable object (function) and the second is the sentinel. The iterator calls this function until the returned value is equal to the sentinel.

int()

>>> 0

inf = iter(int,1)

next(inf)

>>> 0

next(inf)

>>> 0

We can see that the int() function always returns 0. So passing it as iter(int,1) will return an iterator that calls int() until the returned value equals 1. This never happens and we get an infinite iterator.

We can also built our own infinite iterators. The following iterator will, theoretically, return all the odd numbers.

A sample run would be as follows.

a = iter(InfIter())

next(a)

>>> 1

next(a)

>>> 3

next(a)

>>> 5

next(a)

>>> 7

And so on...

Be careful to include a terminating condition, when iterating over these type of infinite iterators.

The advantage of using iterators is that they save resources. In the example above, we could get all of the odd numbers without having to store the entire number system in memory: we can have infinite items (in theory) in finite memory.

Generator

A generator is effectively just a function that returns (data) before it is finished, but it pauses at that point, and you can resume the function at that point.

There is a lot of overhead in building an iterator in Python; we have to implement a class with __iter__() and __next__() method, keep track of internal states, raise StopIteration when there was no values to be returned etc.

This is both lengthy and counter intuitive, if only there was a better way...enter generators. Python generators are really just to create iterators and they handle all of the overhead we mentioned above.

It is fairly simple to create a generator in Python, all we need to do is define a normal function with the yield statement instead of a return statement.

If a function contains at least one yield statement (even if it contains other yield and/or return statements), it becomes a generator function.

Both yield and return will return some value from a function, with the difference being that the yield statement pauses the function, saving its state and later continuing from there for each successive call, unlike terminating a function entirely with a return statement.

The defining factor for a generator functions existence is whether contain or not it contains one or more yield statements.

When called, it returns an object (iterator) but does not start execution immediately.

Methods like __iter__() and __next__() are implemented automatically. So we can iterate through the items using next().

Once the function yields, the function is paused and the control is transferred to the caller.

Local variables and their states are remembered between successive calls.

Finally, when the function terminates, StopIteration is raised automatically on further calls.

Here is an example to illustrate all of the points stated above. We have a generator function named my_gen() with several yield statements.

def my_gen():

n = 1

print('This is printed first')

# Generator function contains yield statements

yield n

n += 1

print('This is printed second')

yield n

n += 1

print('This is printed at last')

yield n

and we can call the generator function in the following manner:

a = my_gen()

next(a)

>>> This is printed first

next(a)

>>> This is printed second

next(a)

>>> This is printed last

next(a)

>>> StopIteration

As you can see, the state of the variable is remembered between each successive call. Normally, these variables would be destroyed when the function yields. Furthermore, the generator object can be iterated only once.

To restart the process we need to create another generator object by assigning it to a variable, like we did with a = my_gen().

One final tip to remember is that we can use generators with for loops directly, because a for loop takes an iterator and iterates over it using next() function:

# A simple generator function

def my_gen():

n = 1

print('This is printed first')

# Generator function contains yield statements

yield n

n += 1

print('This is printed second')

yield n

n += 1

print('This is printed at last')

yield n

# Using for loop

for item in my_gen():

print(item)

The for loop will iterate over the iterator until the last value is reached and then automatically end before a StopIteration is raised.

-

Because they deal with data one piece at a time, you can deal with large amounts of data. With lists, excessive memory requirements could always become a problem.

-

Easy to implement.

# iterator function

class PowTwo:

def __init__(self, max = 0):

self.max = max

def __iter__(self):

self.n = 0

return self

def __next__(self):

if self.n > self.max:

raise StopIteration

result = 2 ** self.n

self.n += 1

return result

vs.

# generator function

def PowTwoGen(max = 0):

n = 0

while n < max:

yield 2 ** n

n += 1

- Generators allow for a natural way to describe infinite streams.

There are also generator expressions (akin to Python's list comprehensions), but with parenthesis around the expression instead of square brackets.

# initialize the list

my_list = [1, 3, 6, 10]

# square each term using list comprehension

[x**2 for x in my_list]

>>> [1, 9, 36, 100]

# same thing can be done using generator expression

(x**2 for x in my_list)

>>> <generator object <genexpr> at 0x0000000002EBDAF8>

# can be printed by wrapping in an iterator (`list` in this case), or iterating over it one by one with `next()`

list((x**2 for x in my_list))

>>> [1, 9, 36, 100]

The major difference between a list comprehension and a generator expression is that while the list comprehension produces the entire list, a generator expression produces only one item at a time.

They are kind of lazy in this regard, producing items only when asked for. For this reason, a generator expression is much more memory efficient than an equivalent list comprehension.

Concurrency

Concurrency is when two or more tasks can start, run and complete in overlapping time periods. It doesn't necessarily mean they'll even be running at the same time though, for example with multi-tasking on a single-core machine. Concurrency is a property of a program or system.

To quote Sun's Multithreaded Programming Guide:

A condition that exists when at least two threads are making progress. A more generalized form of parallelism that can include time-slicing as a form of virtual parallelism.

and also Haskell's Docs:

The term Concurrency refers to techniques that make programs more usable. Concurrency can be implemented and is used a lot on single processing units, nonetheless it may benefit from multiple processing units with respect to speed. If an operating system is called a multi-tasking operating system, this is a synonym for supporting concurrency. If you can load multiple documents simultaneously in the tabs of your browser and you can still open menus and perform other actions, this is concurrency.

If you run distributed-net computations in the background while working with interactive applications in the foreground, that is concurrency. On the other hand, dividing a task into packets that can be computed via distributed-net clients is parallelism.

Parallelism

Parallelism is when tasks literally run at the same time, like on a multicore processor. Parallelism speaks to the run-time behavior of executing multiple tasks at the same time.

To quote Sun's Multithreaded Programming Guide:

A condition that arises when at least two threads are executing simultaneously.

and also Haskell's Docs:

The term Parallelism refers to techniques to make programs faster by performing several computations at the same time. This requires hardware with multiple processing units. In many cases the sub-computations are of the same structure, but this is not necessary. Graphic computations on a GPU are parallelism. A key problem of parallelism is to reduce data dependencies in order to be able to perform computations on independent computation units with minimal communication between them. To this end, it can even be an advantage to do the same computation twice on different units.

-

If you need getNumCapabilities in your program, then your are certainly programming parallelism.

-

If your parallelising efforts make sense on a single processor machine, too, then you are certainly programming concurrency.

Currying

Currying is the process of breaking down a function that takes multiple arguments into a series of functions that take part of the arguments. Let's look at an example in JavaScript:

function add (a, b) {

return a + b;

}

add(3, 4); // returns 7

Now let's look at a function that takes two arguments, a and b, and returns their sum (we will not curry this function):

function add (a) {

return function (b) {

return a + b;

}

}

The above is a function that takes in one argument, a, and returns a function that take another argument, b, and that function finally returns their sum.

add(3)(4);

var add3 = add(3);

add3(4);

The first statement returns 7, like the add(3, 4) statement. The second statement defines a new function called add3 that will add 3 to its argument. This is what some people may call a closure. The third statement uses the add3 operation to add 3 to 4, again producing 7 as a result.

CPU & RAM

- How a CPU works

- How a CPU executes a program

- How computer's calculate - ALU

- Registers and RAM

- Instructions and Programs

- *INC A

- Machine code will usually represent binary patterns in hexadecimal. Hexadecimal is an easy way for humans to remember binary patterns.

- Fetch, Decode, Execute

- For a microprocessor to works the program counter has to contain a memory address that it points to.

Hash Tables (Hash Maps)

| Algorithm | Average | Worst Case |

|---|---|---|

| Space | O(1) | O(n) |

| Search | O(n) | O(n) |

| Insert | O(n) | O(n) |

| Delete | O(n) | O(n) |

Hash Tables, or more commonly implemented as dictionaries in Python, are a type of data structure that stores key-value pairs where the key is generated through a hashing function. This improves the functionality of lookups by a significant margin as the key values themselves act as the index of the array which stores the data. A picture says a thousand words:

>>> a = dict(one=1, two=2, three=3)

>>> b = {'one': 1, 'two': 2, 'three': 3}

>>> c = dict(zip(['one', 'two', 'three'], [1, 2, 3]))

>>> d = dict([('two', 2), ('one', 1), ('three', 3)])

>>> e = dict({'three': 3, 'one': 1, 'two': 2})

>>> a == b == c == d == e

True

dict = {'age': 'Cooper', 'Focus': 'Comp Sci Fundamentals'}

print(dict['age'], dict['Focus'])

>>> Cooper, Comp Sci Fundamentals

When dealing with space vs time tradeoffs, keep Hash Tables at the top of your mind. On average, Hash Tables will out-perform search trees or any other table lookup structure.

- What is a Hash Table? (text)

- Is a Python Dictionary an example of a Hash Table (text)

- Why doesn't Python have a real hashing function?

- Multiple Dict Keys in Python

- Python Equivalent for Hash Map (text)

- Sort Dict by Key (Python)

Hash Tables are widely used in many kinds of computer software, primarily for associate arrays, database indexing, caching, and sets.

A Dictionary in Python, like a hash in Perl or an associative array in PHP, satisfied the requirements to properly represent the implement of a Hash Table:

* The keys of the dictionary are hashable (produces unique values, are not lists).

* The order of the data elements are not fixed.

Linked Lists

On the simplest level, a Linked List is really just a bunch of connected nodes (sub-data structures). The nodes link together to form a list and contain two attributes:

- a value (int, str, objects, etc)

- a pointer to the next node in the sequence

Python lists are resizable, C++ arrays are not C++ arrays are a contiguous allocation of objects in memory, Python lists are a contiguous allocation of references in memory

- Linked Lists in Python (text)

- Linked Lists in Python (video)

- Linked Lists - StackOverflow (text)

- Printing a Singly-Linked List (text)

- Python Linked List (text)

To start off, let's define a few terms:

- Head Node

- The head node is simply the first (root) node in a linked list.

- Tail Node

- The tail node is simply the last node in a linked list. Since it's the last node in the linked list, it must point to NULL as there is no other node in the sequence.

- Singly Linked

- Each node points to a single node in front of it.

- Doubly Linked

- each node can point to two other nodes; one in front and one behind.

With some terminology out of the way, it's almost time to jump into some code examples, but first it's important to touch on the fact that Linked Lists can be as simple or complex as you desire (and the example below is simple).

Since a Linked List is made up of a series of nodes, lets first start by creating a Class for the node:

class Node():

def __init__(self, value, nextNode=None):

self.value = None

self.nextNode = nextNode

If we want to actually populate a node, we simply pass in a value:

firstNode = Node('5')

secondNode = Node('13')

thirdNode = Node('2')

We have created three individual nodes, but now we need to link them together:

firstNode.nextNode = secondNode

secondNode.nextNode = thirdNode

While an extremely simple example, this does provide the basis for understanding what a Linked List in Python looks like on the most basic level.

We may be asked to get the rest of the nodes in the Linked List when provided only with the head, so we would need to find a way to iterate over the list and find what each node is pointing to, and the corresponding node that is pointing to, all the way down the structure until we hit the end (NULL).

currentNode = firstNode

# if the current node is not NULL, move to the next node

while currentNode:

print(currentNode.value)

currentNode = currentNode.nextNode

This is a very basic implementation of a Linked List and how to traverse it, but it's a great way to understand how things work on a simple level.

Unless you are told otherwise, always insert a new element into the tail (last) node in a Linked List.

The simplest way to insert a new value is just like how we create one; by binding the new element to the tail node:

fourthNode = Node('4')

thirdNode.nextNode = fourthNode

Lets jump back to our example a few steps ago that only provides the head node. In order to traverse this list, we can utilize the aforementioned methods to find the tail.

First, lets traverse through the list and check if the node is NULL or populated. If it's not, we stop on the last populated node and set the nextNode equal to the value we wish to insert:

def insertNode(head, value):

currentNode = head

while currentNode:

while not currentNode.nextNode:

currentNode.nextNode = Node(value)

return head

currentNode = currentNode.nextNode

Deleting within a Linked List can get a bit tricky, so let's look at a few examples.

If we wanted to "delete" the 13, all we would need to do is point the 5 to the 2 so that the 13 is never referenced:

5 -> 13 -> 2 -> NULL

becomes

5 -> 2 -> NULL

In order to do implement this process in a streamlined manner we now need to keep track of not just the currentNode but also the previousNode. This also means accounting for the head node being the node we wish to delete.

There are very many ways to accomplish this task and this implementation is not the most optimal, but the example I have chosen is easy to understand. See the code below:

def deleteNode(head, valueToDelete):

currentNode = head

previousNode = None

while currentNode:

if currentNode.value == valueToDelete:

if not previousNode:

newHead = currentNode.nextNode

currentNode.nextNode = None

return newHead

previousNode.nextNode = currentNode.nextNode

return head

previousNode = currentNode

currentNode = currentNode.nextNode

return head

In the above block of code, after finding the node we wish to delete, we set the previous node's nextNode to the deleted node's nextNode to once again effectively remove it from the list.

Let's evaluate the time complexities surrounding the above example (which is something you would implement in an interview, in more real-world scenarios you can store attribuets in a LinkedList class to lower the complexities).

Lets state n is equal to the number of elements inside a Linked List.

What are the following time complexities?

- Traversing

- O(n)

- Traversing a list will always require iterating over n elements.

- Theta(n). (?)

- O(n)

- Tail insertion

- O(n)

- Requires traversing the list to insert our new node.

- Theta(n).

- O(n)

- Head insertion

- O(1)

- We always know where the index of head is within the list, so the best case time complexity is O(1).

- Theta(1).

- O(1)

- Deleting

- O(n)

- Requires traversing the list to delete our new node.

- Omega(1), worst case O(n).

- O(n)

This should act as a rough introduction to Linked Lists in Python; thanks for checking it out :).

In summary, Linked Lists are just a bunch of connected nodes that point to one other node (singly-linked) or up to two other nodes (doubly-linked). A node within a Linked List can only contain two attributes: a value (int, str, etc) and a pointer to the next node in the sequence. Linked Lists seem to be commonplace in technical interviews, so this section is likely one I will come back to often.

The benefit of a linked list is that it can provide list insertion and deletions of a node in O(1) instead of O(n).

Matrices (2D Arrays)

Put simply, a matrix is a two-dimensional data structure where the numbers are divided into rows and columns:

0 0 0 0 0

1 1 1 1 1

0 0 0 0 0

A 3x5 ("three by five") Matrix, as it has 3 rows and 5 columns.

You are most commonly going to see these implement in the form of questions surrounding 2D arrays (which is basically a matrix).

Python doesn't have built in matrices, however for basic tasks we can implement this using a list of lists:

x = [[0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0]]

When diving into more complex computational tasks, the proper way to implement a Matrix is through the package. NumPy is basically the defacto package for scientific computing and it has great support for a powerful N-dimensional array object.

NumPy provides a multidimensional array of numbers (which is actually just an object). See the example below:

import numpy as np

a = np.array([1, 2, 3])

print(a) # Output: [1, 2, 3]

print(type(a)) # Output: <class 'numpy.ndarray'>

You can see in the above that the NumPy array class is called ndarray. Utilizing NumPy to create matrices will allow a massive amount of computational efficiency vs lists, along with a higher degree of control.

Similarly to lists, we can traverse matrices using an index. See the below example of a 1 dimensional NumPy array:

import numpy as np

A = np.array([2, 4, 6, 8, 10])

print("A[0] =", A[0]) # First element

print("A[2] =", A[2]) # Third element

print("A[-1] =", A[-1]) # Last element

Now, let's say we need to traverse a 2D array (matrix).

First, let's see how we would extract the elements:

import numpy as np

A = np.array([[1, 4, 5, 12],

[-5, 8, 9, 0],

[-6, 7, 11, 19]])

# First element of first row

print("A[0][0] =", A[0][0])

# Third element of second row

print("A[1][2] =", A[1][2])

# Last element of last row

print("A[-1][-1] =", A[-1][-1])

>>> A[0][0] = 1

>>> A[1][2] = 9

>>> A[-1][-1] = 19

And the rows:

import numpy as np

A = np.array([[1, 4, 5, 12],

[-5, 8, 9, 0],

[-6, 7, 11, 19]])

print("A[0] =", A[0]) # First Row

print("A[2] =", A[2]) # Third Row

print("A[-1] =", A[-1]) # Last Row (3rd row in this case)

>>> A[0] = [1, 4, 5, 12]

>>> A[2] = [-6, 7, 11, 19]

>>> A[-1] = [-6, 7, 11, 19]

The columns:

import numpy as np

A = np.array([[1, 4, 5, 12],

[-5, 8, 9, 0],

[-6, 7, 11, 19]])

print("A[:,0] =",A[:,0]) # First Column

print("A[:,3] =", A[:,3]) # Fourth Column

print("A[:,-1] =", A[:,-1]) # Last Column (4th column in this case)

>>> A[:,0] = [ 1 -5 -6]

>>> A[:,3] = [12 0 19]

>>> A[:,-1] = [12 0 19]

The above array manipulation is known as slicing matrices and is essentially the same thing as how slicing for lists in Python work. See the brief snapshot below:

a[start:end] # items start through end-1

a[start:] # items start through the rest of the array

a[:end] # items from the beginning through end-1

a[:] # a copy of the whole array

a[start:end:step] # start through not past end, by step

--------------------------------------------------------------------

a[-1] # last item in the array

a[-2:] # last two items in the array

a[:-2] # everything except the last two items

a[::-1] # all items in the array, reversed

a[1::-1] # the first two items, reversed

a[:-3:-1] # the last two items, reversed

a[-3::-1] # everything except the last two items, reversed

One way to remember how slices work is to think of the indices as pointing between characters, with the left edge of the first character numbered 0. Then the right edge of the last character of a string of n characters has index n.

If we wanted to slice a matrix, we would do as follows:

import numpy as np

A = np.array([[1, 4, 5, 12, 14],

[-5, 8, 9, 0, 17],

[-6, 7, 11, 19, 21]])

print(A[:2, :4]) # two rows, four columns

''' Output:

[[ 1 4 5 12]

[-5 8 9 0]]

'''

print(A[:1,]) # first row, all columns

''' Output:

[[ 1 4 5 12 14]]

'''

print(A[:,2]) # all rows, second column

''' Output:

[ 5 9 11]

'''

print(A[:, 2:5]) # all rows, third to fifth column

'''Output:

[[ 5 12 14]

[ 9 0 17]

[11 19 21]]

'''

This is just a high level overview, but it still provides a good baseline for working with matrices in Python.

Matrices are two-dimensional data structures that allow us to store data in the forms of columns and rows. The most common place to encounter matrices are in the form of questions surrounding 2D arrays (which is basically a matrix).

Binary Trees

Graphs

Stacks

Queues

Heaps

Asymptotic Notation (Big O)

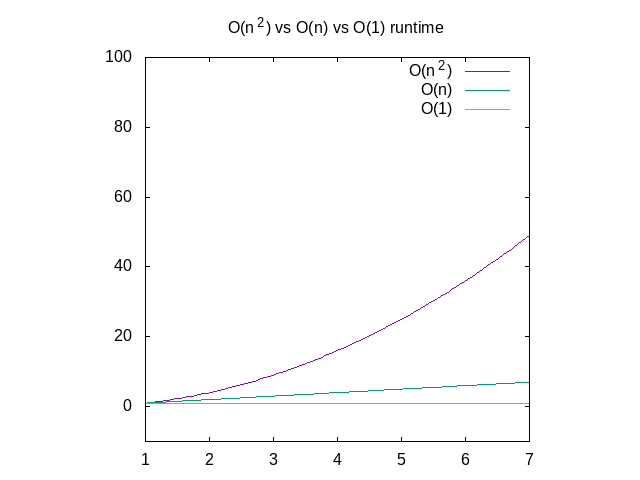

Asymptotic Notation, aka Big O notation, is the most common metric for calculating time complexity. In simpler terms, Big O notation is how programmers talk about algorithms. A functions Big O notation is determined by how it responds to different inputs. How much slower is it if we feed in a list of 1,000,000 elements instead of 1? Big O describes the number of steps it takes to reach the base case.

- The best high-level explanation I've seen to date.

- More later...

Fast or efficient algorithms =/= a measurement in real time (seconds, minutes) due to how much hardware varies, or that a user might be running their program through a different piece of software, etc. Thus, the uniform way compare the algorithm is to measure the Asymptotic Complexity of a program, and to use the notation (Big O (or just O)) for describing this. How fast a programs runtime grows asymptotically == as the size of your inputs increase towards infinity, how does the runtime of your program grow?

Imagine counting the number of characters in a string the simplest way by walking through the whole string, letter by letter, and adding 1 to a counter for each character.

def string_length(strng):

counter = 0

for character in strng:

counter += 1

return counter

This algorithm is said to run in linear time with respect to the number of characters (n) in the string. In short, it runs in O(n); the time required to traverse the entire string is proportional to the number of characters. 20 characters take twice as long as 10 characters, etc. As you increase the number of characters, the runtime will increase linearly with the input length.

Lets says the above method isn't fast enough, so you may chose to store the number of characters in the string in a variable len, which you can then compare against instead of the checking the string itself everytime.

def string_length(strng):

counter = len(strng)

return counter

Accessing len() is considered an asymptotically constant time operation, or O(1). What this means is no matter how big your input is it will always take you the same amount of time to compute things. This doesn't have to mean your code runs in one step; if it doesn't change with the size of inputs then it is still asymptotically constant. There are always drawbacks though and in this case you have to spend extra memory space on your computer to store the variable (and the storage of the variable itself). Constant time is considered the best case scenario for a function.

There are many different Big O runtimes to measure algorithms with. One area you may run into O(n^2) notations is with combinations and it is especially useful when it comes to data structures. See the following code example which would match every item in the list with every other item in the list:

def all_combinations(array):

results = []

for item in array:

for inner_item in array:

results.append((item, inner_item))

return results

This function (algorithm) is considered O(n^2) as every input requires us to do n more operations; n*n == n^2. Thus, O(n^2) are asymptotically slower than O(n) algorithms, but this doesn't mean O(n) algorithms will always run faster, even in the same environment and the same hardware; maybe for small input sizes O(n) could be faster, but as you approach towards infinity O(n^2) will eventually overtake O(n); just like any quadratic mathematical function will eventually overtake any linear function, no matter how much of a head start the linear function starts off with.

Another asymptotic complexity is logarithmic time; O(log n). An example of an algorithm that runs this quickly is the classic Binary Search Algorithm for finding an element in an already sorted list on elements.

Let's say we are looking for the number 3 in the following array of integers [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7].

The Binary Search Algorithm looks at the middle element of the array and asks: is the element greater than, less than, or equal to the element we are looking for?

If it finds the desired element, then you are done. If it's greater than the desired element, then it has to be in the right side of the array and you can only look at that in the future. If it's less than the desired element, you would do the same for the left side. This process is then repeated with the smaller size array until the desired element is found.

To further expand on the point, let's say we had an array with the below sizes:

size 8 -> 3 operations (log₂8)

size 16 -> 4 operations (log₂16)

If we were to double the size of the array then the runtime would only be increased by a single chunk of the code (splitting the middle element and checking) and is therefore said to run in logarithmic time.

Because an algorithm could potentially find the match on the first operation regardless of the input size, Computer Scientists have established a practice of measuring the upper and lower bounds of a runtime (the best and worst case performances of an algorithm), or Omega.

Continuing with the above notation of O(log n), our best case scenario is one where the element is right in the middle and thus one of constant time; we get the element in one operation no matter how big the array is. Thus, the best possible runtime for this algorithm is said to run in Omega(1) time. In the worst case scenario, it will run in O(log n) time as it has to perform O(log n) split-checks of the array to find the correct element.

By contrast, a Linear Search Algorithm (like the first string example) is one where we step through each individual character in the string, which means at best it is Omega(1) and at worst it is O(n).

The last keyword to touch on is Theta, which is used when the best and the worst case scenario runtimes are the same. Our second string problem is an example of this. No matter what number we store in the variable len, we will have to look at it. The best case is we look at it and find the element. The worst case is we look at it and find the element. Therefore the runtime would be labeled as Theta(1), as both the best and worse case scenarios are O(1) (constant time).

In summary, we have good ways to reason about code's efficiency without knowing anything about the real world time they take the run (which is affected by an incredible number of different factors). It also allows us to reason well about what will happen when the size of the inputs increases towards infinity.

ERD

In order to understand how the many elements of a database interact with eachother can be a daunting task, which is why Engineeers build Entity Relationship Diagrams, or ERD's for short.

First off, let's define a few terms:

- Entity