Scheduling is a hot topic in distributed systems which deal with efficiently managing services at datecenter level scales. This was pioneered by Google with their Borg system (developed in 2002).

Google's Borg system is a cluster manager that runs hundreds of thousands of jobs, from many thousands of different applications, across a number of clusters each with up to tens of thousands of machines. It achieves high utilization by combining admission control, efficient task-packing, over-commitment, and machine sharing with process-level performance isolation. It supports high-availability applications with runtime features that minimize fault-recovery time, and scheduling policies that reduce the probability of correlated failures.

Inspired from Borg other schedulers were developed most notably Apache Messos and the YARN scheduler for the Hadoop ecosystem. Both of these are open source while Borg is proprietary and only available inside Google.

A datacenter scheduler's goal is to automate scheduling of work on available resources in way that is optimal and automatic. It provides three main benefits: it (1) hides the details of resource management and failure handling so its users can focus on application development instead; (2) operates with very high reliability and availability, and supports applications that do the same; and (3) lets us run workloads across tens of thousands of machines effectively.

The resources that are scheduled need however to meet certain criteria. Idly they are statically linked to reduce dependencies on their runtime environment, and structured as packages of binaries and data files, whose installation is orchestrated by the scheduler.

Studies indicate that datacenter servers operate, most of the time, at between 10% and 50% of their maximal utilization, and that idle/under-utilized servers consume about 50% of their peak power. Increasing utilization by a few percentage points can save millions of dollars at scale. So let's do some calculations:

1 server in AWS (m5.2xlarge) with 8vCPU and 32GB of RAM is $0.384 per hour. This will cost us $3363.84 per year. 10 servers like this will cost us $33,638.4 per year. 100 servers like this will cost us $336,384 per year.

If you're running at 50% utilization on average you're loosing $168,192 a year. The goal is to improve utilization thus decreasing the cost(e.g number of servers you pay for).

Kubernetes is a platform for automating deployment, scaling, and operations. All of these actions we will group under a single word "scheduling" which encompases all of them. As such we will refer to "Kubernetes" as the "scheduler". The actual objects which are beeing scheduled are "containers". Kubernetes takes a lot of ideas from "Borg" and adds some new things to the mix as well. When looking at how this changes the picture of deployment we can draw these conclusions:

- The

Old Wayto deploy applications was to install the applications on a host using the operating system package manager. This had the disadvantage of entangling the applications’ executables, configuration, libraries, and lifecycles with each other and with the host OS. One could build immutable virtual-machine images in order to achieve predictable rollouts and rollbacks, but VMs are heavyweight and non-portable (for example our internal environment requires VMDK images for VMWare while our cloud deployment relies on AMI that run on AWS. If we factor in that at some point we might move from AWS the situation becomes even more dire). - The

New Wayis to deploy containers based on operating-system-level virtualization rather than hardware virtualization. These containers are isolated from each other and from the host: they have their own filesystems, they can’t see each others’ processes, and their computational resource usage can be bounded. They are easier to build than VMs, and because they are decoupled from the underlying infrastructure and from the host filesystem, they are portable across clouds and OS distributions. Because containers are small and fast, one application can be packed in each container image. This one-to-one application-to-image relationship unlocks the full benefits of containers. With containers, immutable container images can be created at build/release time rather than deployment time, since each application doesn’t need to be composed with the rest of the application stack, nor married to the production infrastructure environment. Generating container images at build/release time enables a consistent environment to be carried from development into production. Similarly, containers are vastly more transparent than VMs, which facilitates monitoring and management. This is especially true when the containers’ process lifecycles are managed by the infrastructure rather than hidden by a process supervisor inside the container. Finally, with a single application per container, managing the containers becomes tantamount to managing deployment of the application. At a minimum, Kubernetes can schedule and run application containers on clusters of physical or virtual machines. However, Kubernetes also allows developers to 'cut the cord' to physical and virtual machines, moving from a host-centric infrastructure to a container-centric infrastructure, which provides the full advantages and benefits inherent to containers. Kubernetes provides the infrastructure to build a truly container-centric development environment.

For a datacenter scheduler to be successful it needs to operate uniformly over a set of applications. As these application can differ a lot depending on languages, dependencies, runtimes and many more factor ideal we would package them in something "static" that abstracts all this complexity from the scheduler. Enter containers.

Linux has the notion of namespaces which you can think of views over resouces. The purpose of each namespace is to wrap a particular global system resource in an abstraction that makes it appear to the processes within the namespace that they have their own isolated instance of the global resource. By default all processes start in the root namespace, however you can create your own namespaces so that the process can have a different view of the world. The linux kernel supports 6 namespaces right now:

- Mount namespaces isolate the set of filesystem mount points seen by a group of processes. Thus, processes in different mount namespaces can have different views of the filesystem hierarchy. With the addition of mount namespaces, the mount() and umount() system calls ceased operating on a global set of mount points visible to all processes on the system and instead performed operations that affected just the mount namespace associated with the calling process. One use of mount namespaces is to create environments that are similar to chroot jails. However, by contrast with the use of the chroot() system call, mount namespaces are a more secure and flexible tool for this task. Other more sophisticated uses of mount namespaces are also possible. For example, separate mount namespaces can be set up in a master-slave relationship, so that the mount events are automatically propagated from one namespace to another; this allows, for example, an optical disk device that is mounted in one namespace to automatically appear in other namespaces.

- UTS namespaces isolate two system identifiers—nodename and domainname—returned by the uname() system call; the names are set using the sethostname() and setdomainname() system calls. In the context of containers, the UTS namespaces feature allows each container to have its own hostname and NIS domain name. This can be useful for initialization and configuration scripts that tailor their actions based on these names. The term "UTS" derives from the name of the structure passed to the uname() system call: struct utsname. The name of that structure in turn derives from "UNIX Time-sharing System".

- IPC namespaces isolate certain interprocess communication (IPC) resources, namely, System V IPC objects. The common characteristic of these IPC mechanisms is that IPC objects are identified by mechanisms other than filesystem pathnames. Each IPC namespace has its own set of System V IPC identifiers and its own POSIX message queue filesystem.

- PID namespaces isolate the process ID number space. In other words, processes in different PID namespaces can have the same PID. One of the main benefits of PID namespaces is that containers can be migrated between hosts while keeping the same process IDs for the processes inside the container. PID namespaces also allow each container to have its own init (PID 1), the "ancestor of all processes" that manages various system initialization tasks and reaps orphaned child processes when they terminate. From the point of view of a particular PID namespace instance, a process has two PIDs: the PID inside the namespace, and the PID outside the namespace on the host system. PID namespaces can be nested: a process will have one PID for each of the layers of the hierarchy starting from the PID namespace in which it resides through to the root PID namespace. A process can see (e.g., view via /proc/PID and send signals with kill()) only processes contained in its own PID namespace and the namespaces nested below that PID namespace.

- Network namespaces provide isolation of the system resources associated with networking. Thus, each network namespace has its own network devices, IP addresses, IP routing tables, /proc/net directory, port numbers, and so on. Network namespaces make containers useful from a networking perspective: each container can have its own (virtual) network device and its own applications that bind to the per-namespace port number space; suitable routing rules in the host system can direct network packets to the network device associated with a specific container. Thus, for example, it is possible to have multiple containerized web servers on the same host system, with each server bound to port 80 in its (per-container) network namespace.

- User namespaces isolate the user and group ID number spaces. In other words, a process's user and group IDs can be different inside and outside a user namespace. The most interesting case here is that a process can have a normal unprivileged user ID outside a user namespace while at the same time having a user ID of 0 inside the namespace. This means that the process has full root privileges for operations inside the user namespace, but is unprivileged for operations outside the namespace.

Cgroups allow you to allocate resources — such as CPU time, system memory, network bandwidth, or combinations of these resources — among user-defined groups of tasks (processes) running on a system. You can monitor the cgroups you configure, deny cgroups access to certain resources, and even reconfigure your cgroups dynamically on a running system. How Control Groups Are Organized Cgroups are organized hierarchically, like processes, and child cgroups inherit some of the attributes of their parents. However, there are differences between the two models. The Linux Process Model All processes on a Linux system are child processes of a common parent: the init process, which is executed by the kernel at boot time and starts other processes (which may in turn start child processes of their own). Because all processes descend from a single parent, the Linux process model is a single hierarchy, or tree. Additionally, every Linux process except init inherits the environment (such as the PATH variable) and certain other attributes (such as open file descriptors) of its parent process. The Cgroup Model Cgroups are similar to processes in that:

-

they are hierarchical, and

-

child cgroups inherit certain attributes from their parent cgroup.

The fundamental difference is that many different hierarchies of cgroups can exist simultaneously on a system. If the Linux process model is a single tree of processes, then the cgroup model is one or more separate, unconnected trees of tasks (i.e. processes). Multiple separate hierarchies of cgroups are necessary because each hierarchy is attached to one or more subsystems The following cgroups are available on a RHEL7 server:

-

blkio — this subsystem sets limits on input/output access to and from block devices such as physical drives (disk, solid state, or USB).

-

cpu — this subsystem uses the scheduler to provide cgroup tasks access to the CPU.

-

cpuacct — this subsystem generates automatic reports on CPU resources used by tasks in a cgroup.

-

cpuset — this subsystem assigns individual CPUs (on a multicore system) and memory nodes to tasks in a cgroup.

-

devices — this subsystem allows or denies access to devices by tasks in a cgroup.

-

freezer — this subsystem suspends or resumes tasks in a cgroup.

-

memory — this subsystem sets limits on memory use by tasks in a cgroup and generates automatic reports on memory resources used by those tasks.

-

net_cls — this subsystem tags network packets with a class identifier (classid) that allows the Linux traffic controller (tc) to identify packets originating from a particular cgroup task.

-

net_prio — this subsystem provides a way to dynamically set the priority of network traffic per network interface.

-

ns — the namespace subsystem.

By default all OS components start in the root cgroup which is unrestricted (doesn't have any cgroup limitations defined on it). The systemd-cgtop tool shows each group (you will see them a slices) and the resouces each group uses:

Path Tasks %CPU Memory Input/s Output/s

/ 347 19.6 7.0G - -

/system.slice 82 13.3 2.6G - -

/system.slice/kubelet.service 2 11.5 53.6M - -

/kubepods.slice - 4.2 741.2M - -

/kubepods.slice/kubepods-burstable.slice - 3.5 346.6M - -

/kubepods.slice/kubepods-burstable.slice/kubepods-burstable-pod1a4337e331349a4034ee871801eb6c7f.slice - 2.2 63.1M - -

/user.slice 8 2.0 601.5M - -

/kubepods.slice/kubepods-burstable.slice/kubepods-burstable-pod1794e279e23483f245a1bc8ae4eb2f9b.slice - 1.1 177.4M - -

/system.slice/kafka.service 1 0.8 830.1M - -

/kubepods.slice/kubepods-besteffort.slice - 0.6 394.5M - -

/system.slice/docker.service 21 0.5 150.4M - -

/kubepods.slice/kubepods-besteffort.slice/kubepods-besteffort-podba6d8f264fe61854f46e7eacbd626a92.slice - 0.5 300.5M - -

/kubepods.slice/kubepods-burstable.slice/kubepods-burstable-poda0f6609c_917d_11e7_9439_02ecb0828e42.slice - 0.2 72.3M - -

/kubepods.slice/kubepods-besteffor...ice/kubepods-besteffort-poda0ef9a35_917d_11e7_9439_02ecb0828e42.slice - 0.1 34.7M - -

/system.slice/ocm.service 2 0.1 286.5M - -

/system.slice/zookeeper.service 1 0.1 165.4M - -

/system.slice/goferd.service 1 0.1 27.2M - -

- the system.slice refers to the route group.

- kubepods.slice refers to the kubernets groups. Inside them there will be individual groups for each pod and container in the pod.

To identify the container/pod you want to check the groups status information for you will first need to get the docker container ID from kubernetes using kubectl -n ns-org-1 describe pod <POD_NAME>. This will also tell you the node on which the pod is currently scheduled so you can login there to get more info. Stats for the entire pod are available usualy under kubepods slice on the kubernetes node. To get the actual UID of the slice run the command systemd-cgls which provides a list of all cgroups running on the machine.

root@k00003-b0ie ~]# systemd-cgls

├─1 /usr/lib/systemd/systemd --switched-root --system --deserialize 22

├─kubepods.slice

│ ├─kubepods-podad7ab520_9ed8_11e7_979f_02ecb0828e42.slice

│ │ ├─docker-4d66e74bd8ff3f538102dab400028f7162120b075ab29633df5762797c56c12e.scope

│ │ │ ├─ 3647 sleep 3m

│ │ │ ├─17650 /bin/sh -c /helpers/init.sh

│ │ │ ├─17667 /bin/sh /helpers/init.sh

│ │ │ ├─17675 /opt/td-agent/embedded/bin/ruby /usr/sbin/td-agent -qq --use-v1-config --suppress-repeated-stacktrace

│ │ │ └─17697 /opt/td-agent/embedded/bin/ruby /usr/sbin/td-agent -qq --use-v1-config --suppress-repeated-stacktrace

│ │ ├─docker-a60d3c296f60af17f289a855a8412b6a98cb43cd625a1b39d33a8cfc7e3de207.scope

│ │ │ ├─ 3889 sleep 1m

│ │ │ ├─17390 /bin/sh /tools/init.sh

│ │ │ ├─17474 /bin/sh /opt/optymyze/loginserver/run-loginserver.sh -Xms384m -Xmx384m -XX:+HeapDumpOnOutOfMemoryError -javaagent:/tools/jmx_prometh

│ │ │ └─17481 java -cp lib/* -Xms384m -Xmx384m -XX:+HeapDumpOnOutOfMemoryError -javaagent:/tools/jmx_prometheus_javaagent-0.9.jar=28695:/tools/prome

│ │ └─docker-4a81002b70461359ad94d88cae7ed669402a6de6d164a479d3f5c32b8ad11150.scope

│ │ └─16182 /pause

│ ├─kubepods-podacd4d7e2_9ed8_11e7_979f_02ecb0828e42.slice

│ │ ├─docker-998e9560a6ce1a0f4fe468d8448187060960583881414c4f370df6799b296d41.scope

│ │ │ ├─ 3783 sh

│ │ │ ├─ 3890 sleep 1m

│ │ │ ├─ 3974 su - optymyze

│ │ │ ├─ 3975 -sh

│ │ │ ├─ 4323 java -cp ../lib/webworkerdispatcher/*:../lib/webdispatcher/*:../lib/workerdispatcher/*:../lib/dispatcher/* -Xms512m -Xmx512m -javaagen

│ │ │ ├─ 8048 sh

│ │ │ ├─ 9385 sudo su - optymyze

│ │ │ ├─ 9386 su - optymyze

│ │ │ ├─ 9387 -sh

│ │ │ ├─30466 /bin/sh /tools/init.sh

│ │ │ └─30520 /opt/farmount/farmount

│ │ ├─docker-23f0d3a5a778145d9bd8df80de93872fa73f9d0c4be95c3f89c5285c3f089216.scope

│ │ │ ├─ 3646 sleep 3m

│ │ │ ├─17547 /bin/sh -c /helpers/init.sh

│ │ │ ├─17595 /bin/sh /helpers/init.sh

│ │ │ ├─17604 /opt/td-agent/embedded/bin/ruby /usr/sbin/td-agent -qq --use-v1-config --suppress-repeated-stacktrace

│ │ │ └─17693 /opt/td-agent/embedded/bin/ruby /usr/sbin/td-agent -qq --use-v1-config --suppress-repeated-stacktrace

│ │ └─docker-12cfe4aab82d5e7f21cb54f326998a7f7f60361a696d0c25623b7eca83cbba01.scope

│ │ └─15814 /pause

│ ├─kubepods-besteffort.slice

│ │ ├─kubepods-besteffort-podc2d0786e_9182_11e7_979f_02ecb0828e42.slice

│ │ │ ├─docker-c055f821b65a0f2941c71605f03eae6157b373fb2010065009ca2ce1dd8f4f43.scope

│ │ │ │ └─26174 /usr/local/bin/kube-proxy --kubeconfig=/var/lib/kube-proxy/kubeconfig.conf --cluster-cidr=10.255.128.0/17

│ │ │ └─docker-86cc1bb4fd61e76c59613d94d5a57978192eed9797f20f5c1cc6142ba49b3213.scope

│ │ │ └─25686 /pause

│ │ └─kubepods-besteffort-podc2d06ff1_9182_11e7_979f_02ecb0828e42.slice

│ │ ├─docker-6ee4f6b85436536910acafe27745af2c59af5f5596d66c6afd41fb13fe603425.scope

│ │ │ ├─ 6689 /bin/sh -c set -e -x; cp -f /etc/kube-flannel/cni-conf.json /etc/cni/net.d/10-flannel.conf; while true; do sleep 3600; done

│ │ │ └─29459 sleep 3600

│ │ ├─docker-4e6300b6e0ffad097742117f504c101008768e68e3b35e67aee090a6bfd4d07b.scope

│ │ │ └─6596 /opt/bin/flanneld --ip-masq --kube-subnet-mgr

│ │ └─docker-05c4dc203857b25b83a3beda3f25074e69fb34757f88e030e9f2a71146695c3b.scope

│ │ └─25990 /pause

In our case to see the login server pod details we ca see the kube pod slice to be kubepods-podad7ab520_9ed8_11e7_979f_02ecb0828e42.slice while the container id is docker-a60d3c296f60af17f289a855a8412b6a98cb43cd625a1b39d33a8cfc7e3de207.scope

To get for example the memory stats of the docker-a60d3c296f60af17f289a855a8412b6a98cb43cd625a1b39d33a8cfc7e3de207.scope container we will need to cat the file /sys/fs/cgroup/memory/kubepods.slice/kubepods-podacd4d7e2_9ed8_11e7_979f_02ecb0828e42.slice/docker-998e9560a6ce1a0f4fe468d8448187060960583881414c4f370df6799b296d41.scope/memory.stat

[root@k00003-b0ie ~]# cat /sys/fs/cgroup/memory/kubepods.slice/kubepods-podacd4d7e2_9ed8_11e7_979f_02ecb0828e42.slice/docker-998e9560a6ce1a0f4fe468d8448187060960583881414c4f370df6799b296d41.scope/memory.stat

cache 137879552

rss 887947264

rss_huge 773849088

mapped_file 18018304

swap 1064960

pgpgin 15134965

pgpgout 15121112

pgfault 66788875

pgmajfault 721

inactive_anon 480665600

active_anon 407281664

inactive_file 51650560

active_file 86228992

unevictable 0

hierarchical_memory_limit 1073741824

hierarchical_memsw_limit 2147483648

total_cache 137879552

total_rss 887947264

total_rss_huge 773849088

total_mapped_file 18018304

total_swap 1064960

total_pgpgin 15134965

total_pgpgout 15121112

total_pgfault 66788875

total_pgmajfault 721

total_inactive_anon 480665600

total_active_anon 407281664

total_inactive_file 51650560

total_active_file 86228992

total_unevictable 0

For us two groups are very important and we will continue to focus on them. One is the memory group and the cpu cgroups.

-

Memory cgroup

The memory subsystem generates automatic reports on memory resources used by the tasks in a cgroup, and sets limits on memory use of those tasks. The information about the memory group are available on the machine at sys/fs/cgroup/memory location:

[root@k00001-b0ie ~]# ls -lp /sys/fs/cgroup/memory/ total 0 -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 cgroup.clone_children --w--w--w- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 cgroup.event_control -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 cgroup.procs -r--r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 cgroup.sane_behavior drwxr-xr-x 4 root root 0 Sep 4 12:37 kubepods.slice/ drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 0 Sep 4 12:37 machine.slice/ -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.failcnt --w------- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.force_empty -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.kmem.failcnt -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.kmem.limit_in_bytes -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.kmem.max_usage_in_bytes -r--r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.kmem.slabinfo -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.kmem.tcp.failcnt -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.kmem.tcp.limit_in_bytes -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.kmem.tcp.max_usage_in_bytes -r--r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.kmem.tcp.usage_in_bytes -r--r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.kmem.usage_in_bytes -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.limit_in_bytes -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.max_usage_in_bytes -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.memsw.failcnt -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.memsw.limit_in_bytes -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.memsw.max_usage_in_bytes -r--r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.memsw.usage_in_bytes -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.move_charge_at_immigrate -r--r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.numa_stat -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.oom_control ---------- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.pressure_level -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.soft_limit_in_bytes -r--r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.stat -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.swappiness -r--r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.usage_in_bytes -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 memory.use_hierarchy -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 notify_on_release -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 release_agent drwxr-xr-x 106 root root 0 Oct 2 12:00 system.slice/ -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 1 14:55 tasks drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 0 Sep 4 12:14 user.slice/What stands out for us at this location is the

user.slice(user processes),system.slice(system process) andkubepods.slice(kubernetes pods). You can use the kubepods.slice to drill down in terms of memory usage to the entire slice (all pods running), per pod, or per container inside the pod. Each of them will present you the same hierarchy. The following files are of importance for understanding the memory usage of the application inside the respective memory group:-

memory.stat. This file reports a wide range of memory statistics, as described in the following table:

Statistic Description cache page cache, including tmpfs (shmem), in bytes rss anonymous and swap cache, not including tmpfs (shmem), in bytes mapped\_file size of memory-mapped mapped files, including tmpfs (shmem), in bytes pgpgin number of pages paged into memory pgpgout number of pages paged out of memory swap swap usage, in bytes active\_anon anonymous and swap cache on active least-recently-used (LRU) list, including tmpfs (shmem) inactive\_anon anonymous and swap cache on inactive LRU list, including tmpfs (shmem), in bytes active\_file file-backed memory on active LRU list, in bytes inactive\_file file-backed memory on inactive LRU list, in bytes unevictable memory that cannot be reclaimed, in bytes hierarchical\_memory\_limit memory limit for the hierarchy that contains the memory cgroup, in bytes hierarchical\_memsw\_limit memory plus swap limit for the hierarchy that contains the memory cgroup, in bytes Additionally, each of these files other than hierarchical_memory_limit and hierarchical_memsw_limit has a counterpart prefixed total_ that reports not only on the cgroup, but on all its children as well. For example, swap reports the swap usage by a cgroup and total_swap reports the total swap usage by the cgroup and all its child groups. When you interpret the values reported by memory.stat, note how the various statistics inter-relate:

- active_anon + inactive_anon = anonymous memory + file cache for tmpfs + swap cache

Therefore, active_anon + inactive_anon ≠ rss, because rss does not include tmpfs.

- active_file + inactive_file = cache - size of tmpfs

-

memory.usage_in_bytes. This file reports the total current memory usage by processes in the cgroup (in bytes).

-

memory.memsw.usage_in_bytes. This file reports the sum of current memory usage plus swap space used by processes in the cgroup (in bytes).

-

memory.max_usage_in_bytes. This file reports the maximum memory used by processes in the cgroup (in bytes).

-

memory.memsw.max_usage_in_bytes. This file reports the maximum amount of memory and swap space used by processes in the cgroup (in bytes).

-

memory.limit_in_bytes. This file sets the maximum amount of user memory (including file cache). If no units are specified, the value is interpreted as bytes. However, it is possible to use suffixes to represent larger units — k or K for kilobytes, m or M for megabytes, and g or G for gigabytes.

-

memory.memsw.limit_in_bytes. This file sets the maximum amount for the sum of memory and swap usage. If no units are specified, the value is interpreted as bytes.

-

memory.failcnt. This file reports the number of times that the memory limit has reached the value set in memory.limit_in_bytes.

-

memory.memsw.failcnt. This file reports the number of times that the memory plus swap space limit has reached the value set in memory.memsw.limit_in_bytes.

-

memory.swappiness. This file sets the tendency of the kernel to swap out process memory used by tasks in this cgroup instead of reclaiming pages from the page cache. This is the same tendency, calculated the same way, as set in /proc/sys/vm/swappiness for the system as a whole. The default value is 60. Values lower than 60 decrease the kernel's tendency to swap out process memory, values greater than 60 increase the kernel's tendency to swap out process memory, and values greater than 100 permit the kernel to swap out pages that are part of the address space of the processes in this cgroup.Note that a value of 0 does not prevent process memory being swapped out; swap out might still happen when there is a shortage of system memory because the global virtual memory management logic does not read the cgroup value. To lock pages completely, use mlock() instead of cgroups.

-

memory.oom_control. This file contains a flag (0 or 1) that enables or disables the Out of Memory killer for a cgroup. If enabled (0), tasks that attempt to consume more memory than they are allowed are immediately killed by the OOM killer. The OOM killer is enabled by default in every cgroup using the memory subsystem; to disable it, write 1.

~]# echo 1 > /cgroup/memory/lab1/memory.oom_control

-

-

CPU cgroup

The cpu subsystem schedules CPU access to cgroups. Access to CPU resources can be scheduled using two schedulers:

- Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS) — a proportional share scheduler which divides the CPU time (CPU bandwidth) proportionately between groups of tasks (cgroups) depending on the priority/weight of the task or shares assigned to cgroups. This is the default scheduler used by Docker on Linux (and Kubernetes)

- Real-Time scheduler (RT) — a task scheduler that provides a way to specify the amount of CPU time that real-time tasks can use.

In CFS, a cgroup can get more than its share of CPU if there are enough idle CPU cycles available in the system, due to the work conserving nature of the scheduler. This is usually the case for cgroups that consume CPU time based on relative shares. Ceiling enforcement can be used for cases when a hard limit on the amount of CPU that a cgroup can utilize is required (that is, tasks cannot use more than a set amount of CPU time). The following options can be used to configure ceiling enforcement or relative sharing of CPU: Ceiling Enforcement Tunable Parameters

- cpu.cfs_period_us. Specifies a period of time in microseconds (µs, represented here as "us") for how regularly a cgroup's access to CPU resources should be reallocated. If tasks in a cgroup should be able to access a single CPU for 0.2 seconds out of every 1 second, set cpu.cfs_quota_us to 200000 and cpu.cfs_period_us to 1000000. The upper limit of the cpu.cfs_quota_us parameter is 1 second and the lower limit is 1000 microseconds.

- cpu.cfs_quota_us. Specifies the total amount of time in microseconds (µs, represented here as "us") for which all tasks in a cgroup can run during one period (as defined by cpu.cfs_period_us). As soon as tasks in a cgroup use up all the time specified by the quota, they are throttled for the remainder of the time specified by the period and not allowed to run until the next period. If tasks in a cgroup should be able to access a single CPU for 0.2 seconds out of every 1 second, set cpu.cfs_quota_us to 200000 and cpu.cfs_period_us to 1000000. Note that the quota and period parameters operate on a CPU basis. To allow a process to fully utilize two CPUs, for example, set cpu.cfs_quota_us to 200000 and cpu.cfs_period_us to 100000.Setting the value in cpu.cfs_quota_us to -1 indicates that the cgroup does not adhere to any CPU time restrictions. This is also the default value for every cgroup (except the root cgroup).

- cpu.stat. Reports CPU time statistics using the following values:

- nr_periods — number of period intervals (as specified in cpu.cfs_period_us) that have elapsed.

- nr_throttled — number of times tasks in a cgroup have been throttled (that is, not allowed to run because they have exhausted all of the available time as specified by their quota).

- throttled_time — the total time duration (in nanoseconds) for which tasks in a cgroup have been throttled.

Relative Shares Tunable Parameters

- cpu.shares. Contains an integer value that specifies a relative share of CPU time available to the tasks in a cgroup. For example, tasks in two cgroups that have cpu.shares set to 100 will receive equal CPU time, but tasks in a cgroup that has cpu.shares set to 200 receive twice the CPU time of tasks in a cgroup where cpu.shares is set to 100. The value specified in the cpu.shares file must be 2 or higher.

Note that shares of CPU time are distributed per all CPU cores on multi-core systems. Even if a cgroup is limited to less than 100% of CPU on a multi-core system, it may use 100% of each individual CPU core. Consider the following example: if cgroup A is configured to use 25% and cgroup B 75% of the CPU, starting four CPU-intensive processes (one in A and three in B) on a system with four cores results in the following division of CPU shares:

PID cgroup CPU CPU share 100 A 0 100% of CPU0 101 B 1 100% of CPU1 102 B 2 00% of CPU2 103 B 3 100% of CPU3 Using relative shares to specify CPU access has two implications on resource management that should be considered:

- Because the CFS does not demand equal usage of CPU, it is hard to predict how much CPU time a cgroup will be allowed to utilize. When tasks in one cgroup are idle and are not using any CPU time, the leftover time is collected in a global pool of unused CPU cycles. Other cgroups are allowed to borrow CPU cycles from this pool.

- The actual amount of CPU time that is available to a cgroup can vary depending on the number of cgroups that exist on the system. If a cgroup has a relative share of 1000 and two other cgroups have a relative share of 500, the first cgroup receives 50% of all CPU time in cases when processes in all cgroups attempt to use 100% of the CPU. However, if another cgroup is added with a relative share of 1000, the first cgroup is only allowed 33% of the CPU (the rest of the cgroups receive 16.5%, 16.5%, and 33% of CPU).

Another important part of the cgroup CPU scheduling is the accounting that linux keeps. This helps us determine if the allocated shares are sufficient, if the CFS is actively throttling the application and so on. This information can be found in the

/sys/fs/cpuacctsection. CPU Accounting(cpuacct) The CPU cgroup will also provide additional files under the prefix "cpuacct". Those files provide accounting statistics and were previously provided by the separate cpuacct controller. Although the cpuacct controller will still be kept around for compatibility reasons, its usage is discouraged. If both the CPU and cpuacct controllers are present in the system, distributors are encouraged to always mount them together. The files where this information is available are under the/sys/fs/cgroup/cpuacctlocation. These files are:- cpu.shares: The weight of each group living in the same hierarchy, that translates into the amount of CPU it is expected to get. Upon cgroup creation, each group gets assigned a default of 1024. The percentage of CPU assigned to the cgroup is the value of shares divided by the sum of all shares in all cgroups in the same level.

- cpu.cfs_period_us: The duration in microseconds of each scheduler period, for bandwidth decisions. This defaults to 100000us or 100ms. Larger periods will improve throughput at the expense of latency, since the scheduler will be able to sustain a cpu-bound workload for longer. The opposite of true for smaller periods. Note that this only affects non-RT tasks that are scheduled by the CFS scheduler.

- cpu.cfs_quota_us: The maximum time in microseconds during each cfs_period_us in for the current group will be allowed to run. For instance, if it is set to half of cpu_period_us, the cgroup will only be able to peak run for 50 % of the time. One should note that this represents aggregate time over all CPUs in the system. Therefore, in order to allow full usage of two CPUs, for instance, one should set this value to twice the value of cfs_period_us.

- cpu.stat: statistics about the bandwidth controls. No data will be presented if cpu.cfs_quota_us is not set. The file presents three numbers:

- nr_periods: how many full periods have been elapsed.

- nr_throttled: number of times we exausted the full allowed bandwidth

- throttled_time: total time the tasks were not run due to being overquota

- cpu.rt_runtime_us and cpu.rt_period_us: Those files are the RT-tasks analogous to the CFS files cfs_quota_us and cfs_period_us. One important difference, though, is that while the cfs quotas are upper bounds that won't necessarily be met, the rt runtimes form a stricter guarantee. Therefore, no overlap is allowed. Implications of that are that given a hierarchy with multiple children, the sum of all rt_runtime_us may not exceed the runtime of the parent. Also, a rt_runtime_us of 0, means that no rt tasks can ever be run in this cgroup. For more information about rt tasks runtime assignments, see scheduler/sched-rt-group.txt

- cpu.stat_percpu: Various scheduler statistics for the current group. The information provided in this file is akin to the one displayed in /proc/stat, except for the fact that it is cgroup-aware. The file format consists of a one-line header that describes the fields being listed. No guarantee is given that the fields will be kept the same between kernel releases, and readers should always check the header in order to introspect it.

- cpuacct.usage: The aggregate CPU time, in nanoseconds, consumed by all tasks in this group.

- cpuacct.usage_percpu: The CPU time, in nanoseconds, consumed by all tasks in this group, separated by CPU. The format is an space-separated array of time values, one for each present CPU.

- cpuacct.stat: aggregate user and system time consumed by tasks in this group.

The format is

- user: x

- system: y

-

Intro

With Docker people are using the layered security approach, which is "the practice of combining multiple mitigating security controls to protect resources and data."

Basically, docker adds as many security barriers as possible to prevent a break out. If a privileged process can break out of one containment mechanism, we want to block them with the next. Docker takes advantage of as many security mechanisms of Linux as possible to make the system more secure. These include filesystem protections, Linux Capabilities, Namespaces, cgroups and SELinux:

-

File System protections:

-

Read-only mount points Some Linux kernel file systems have to be mounted in a container environment or processes would fail to run. Fortunately, most of these filesystems can be mounted as "read-only". Most apps should never need to write to these file systems. Docker mounts these file systems into the container as "read-only" mount points.

. /sys . /proc/sys . /proc/sysrq-trigger . /proc/irq . /proc/busBy mounting these file systems as read-only, privileged container processes cannot write to them. They cannot effect the host system. Of course, we also block the ability of the privileged container processes from remounting the file systems as read/write. We block the ability to mount any file systems at all within the container. I will explain how we block mounts when we get to capabilities.

-

Copy-on-write file systems Docker uses copy-on-write file systems. This means containers can use the same file system image as the base for the container. When a container writes content to the image, it gets written to a container specific file system. This prevents one container from seeing the changes of another container even if they wrote to the same file system image. Just as important, one container can not change the image content to effect the processes in another container.

-

-

Capabilities Linux capabilities are explained well on their main page:

For the purpose of performing permission checks, traditional UNIX implementations distinguish two categories of processes: privileged processes (whose effective user ID is 0, referred to as superuser or root), and unprivileged processes (whose effective UID is nonzero). Privileged processes bypass all kernel permission checks, while unprivileged processes are subject to full permission checking based on the process's credentials (usually: effective UID, effective GID, and supplementary group list). Starting with kernel 2.2, Linux divides the privileges traditionally associated with superuser into distinct units, known as capabilities, which can be independently enabled and disabled. Capabilities are a per-thread attribute.

Removing capabilities can cause applications to break, which means we have a balancing act in Docker between functionality, usability and security. Here is the current list of capabilities that Docker uses: chown, dac_override, fowner, kill, setgid, setuid, setpcap, net_bind_service, net_raw, sys_chroot, mknod, setfcap, and audit_write.

It is continuously argued back and forth which capabilities should be allowed or denied by default. Docker allows customers to manipulate default list with the command line options for Docker run.

- Capabilities removed

- CAP_SETPCAP - Modify process capabilities

- CAP_SYS_MODULE - Insert/Remove kernel modules

- CAP_SYS_RAWIO - Modify Kernel Memory

- CAP_SYS_PACCT - Configure process accounting

- CAP_SYS_NICE - Modify Priority of processes

- CAP_SYS_RESOURCE - Override Resource Limits

- CAP_SYS_TIME - Modify the system clock

- CAP_SYS_TTY_CONFIG - Configure tty devices

- CAP_AUDIT_WRITE - Write the audit log

- CAP_AUDIT_CONTROL - Configure Audit Subsystem

- CAP_MAC_OVERRIDE - Ignore Kernel MAC Policy

- CAP_MAC_ADMIN - Configure MAC Configuration

- CAP_SYSLOG - Modify Kernel printk behavior

- CAP_NET_ADMIN - Configure the network

- CAP_SYS_ADMIN - Catch all

Lets look closer at the last couple in the table. By removing CAP_NET_ADMIN for a container, the container processes cannot modify the systems network, meaning assigning IP addresses to network devices, setting up routing rules, modifying iptables.

All networking is setup by the Docker daemon before the container starts. You can manage the containers network interface from outside the container but not inside.

CAP_SYS_ADMIN is special capability. I believe it is the kernel catchall capability. When kernel engineers design new features into the kernel, they are supposed to pick the capability that best matches what the feature allows. Or, they were supposed to create a new capability. Problem is, there were originally only 32 capability slots available. When in doubt the kernel engineer would just fall back to using CAP_SYS_ADMIN. Here is the list of things CAP_SYS_ADMIN allows according to /usr/include/linux/capability. The two most important features that removing CAP_SYS_ADMIN from containers does is stops processes from executing the mount syscall or modifying namespaces. You don't want to allow your container processes to mount random file systems or to remount the read-only file systems. We however require these for Optymyze so we run with this capability enabled.

- Capabilities removed

-

-

SELinux

SELinux is a LABELING system where you can define interactions between labels. It also has some nice properties like:

- Every process has a LABEL

- Every file, directory, and system object has a LABEL

- Policy rules control access between labeled processes and labeled objects

- The kernel enforces the rules

The Docker SELinux security policy is similar to the libvirt security policy and is based on the libvirt security policy.The libvirt security policy is a series of SELinux policies that defines two ways of isolating virtual machines. Generally, virtual machines are prevented from accessing parts of the network. Specifically, individual virtual machines are denied access to one another’s resources. Red Hat extends the libvirt-SELinux model to Docker. The Docker SELinux role and Docker SELinux types are based on libvirt. SELinux implements a Mandatory Access Control system. This means the owners of an object have no control or discretion over the access to an object. The kernel enforces Mandatory Access Controls. An explanation on how SELinux enforcement works are available in the visual guide to SELinux policy enforcement (and subsequent, SELinux Coloring Book). The default type used for running Docker containers is svirt_lxc_net_t. All container processes run with this type. All content within the container is labeled with the svirt_sandbox_file_t type. svirt_lxc_net_t is allowed to manage any content labeled with svirt_sandbox_file_t. svirt_lxc_net_t is also able to read/execute most labels under /usr on the host.

Processes running witht he svirt_lxc_net_t are not allowed to open/write to any other labels on the system. It is not allowed to read any default labels in /var, /root, /home etc.

Basically, we want to allow the processes to read/execute system content, but we want to not allow it to use any "data" on the system unless it is in the container, by default. **Problem** If all container processes are run with svirt\_lxc\_net\_t and all content is labeled with svirt\_sandbox\_file\_t, wouldn't container processes be allowed to attack processes running in other containers and content owned by other containers?This is where Multi Category Security enforcement comes in, described below. Alternate Types Notice that Docker used "net" in the type label. This is used to indicate that this type can use full networking.Then the processes inside of the container would not be allowed to use any network ports. Similarly, we could easily write an Apache policy that would only allow the container to listen on Apache ports, but not allowed to connect out on any ports. Using this type of policy you could prevent your container from becoming a spam bot even if it was cracked, and the hacker got control of the apache process within the container. Multi Category Security enforcement Multi Category Security is based on Multi Level Security (MLS). MCS takes advantage of the last component of the SELinux label the MLS Field. MCS enforcement protects containers from each other. When containers are launched the Docker daemon picks a random MCS label, for example s0:c1,c2, to assign to the container. The Docker daemon labels all of the content in the container with this MCS label. When the daemon launches the container process it tells the kernel to label the processes with the same MCS label. The kernel only allows container processes to read/write their own content as long as the process MCS label matches the filesystem content MCS label. The kernel blocks container processes from read/writing content labeled with a different MCS label.

The full description of the SELinux policy docker uses is available at https://www.mankier.com/8/docker_selinux.

-

SecCompare

Secure Computing Mode (seccomp) is a kernel feature that allows you to filter system calls to the kernel from a container. The combination of restricted and allowed calls are arranged in profiles, and you can pass different profiles to different containers. Seccomp provides more fine-grained control than capabilities, giving an attacker a limited number of syscalls from the container. The default seccomp profile for docker is a JSON file and can be viewed here: https://github.com/docker/docker/blob/master/profiles/seccomp/default.json. It blocks 44 system calls out of more than 300 available.Making the list stricter would be a trade-off with application compatibility. A table with a significant part of the blocked calls and the reasoning for blocking can be found here: https://docs.docker.com/engine/security/seccomp/. Seccomp uses the Berkeley Packet Filter (BPF) system, which is programmable on the fly so you can make a custom filter. You can also limit a certain syscall by also customizing the conditions on how or when it should be limited. A seccomp filter replaces the syscall with a pointer to a BPF program, which will execute that program instead of the syscall. All children to a process with this filter will inherit the filter as well. The docker option which is used to operate with seccomp is

--security-opt.

Copy-on-write is a mechanism allowing to share data. The data appears to be a copy, but is only a link (or reference) to the original data. The actual copy happens only when someone tries to change the shared data. Whoever changes the shared data ends up sharing their own copy instead. There are multiple file systems which support copy-on-write semantics but the default one for RHEL systems is devicemapper.

The device mapper graphdriver uses the device mapper thin provisioning module (dm-thinp) to implement CoW snapshots. The preferred model is to have a thin pool reserved outside of Docker and passed to the daemon via the –storage-opt dm.thinpooldev option. Alternatively, the device mapper graphdriver can setup a block device to handle this for you via the –storage-opt dm.directlvm_device option.

As a fallback if no thin pool is provided, loopback files will be created. Loopback is very slow, but can be used without any pre-configuration of storage. It is strongly recommended that you do not use loopback in production. Ensure your Docker daemon has a –storage-opt dm.thinpooldev argument provided.

In loopback, a thin pool is created at /var/lib/docker/devicemapper (devicemapper graph location) based on two block devices, one for data and one for metadata. By default these block devices are created automatically by using loopback mounts of automatically created sparse files. As of docker-1.4.1 and later, docker info when using the devicemapper storage driver will display something like:

$ sudo docker info

[...]

Storage Driver: devicemapper

Pool Name: docker-pool00

Pool Blocksize: 65.54 kB

Base Device Size: 21.47 GB

Backing Filesystem: xfs

Data file:

Metadata file:

Data Space Used: 3.395 GB

Data Space Total: 107.2 GB

Data Space Available: 103.8 GB

Metadata Space Used: 5.034 MB

Metadata Space Total: 104.9 MB

Metadata Space Available: 99.82 MB

Thin Pool Minimum Free Space: 10.72 GB

Udev Sync Supported: true

Deferred Removal Enabled: true

Deferred Deletion Enabled: false

Deferred Deleted Device Count: 0

Library Version: 1.02.135-RHEL7 (2016-11-16)

[...]

There is also the option of OverlayFS, but it's still experimental on RHEL 7. Probably when RHEL8 is released it will be the default copy-on-write backend for containers.

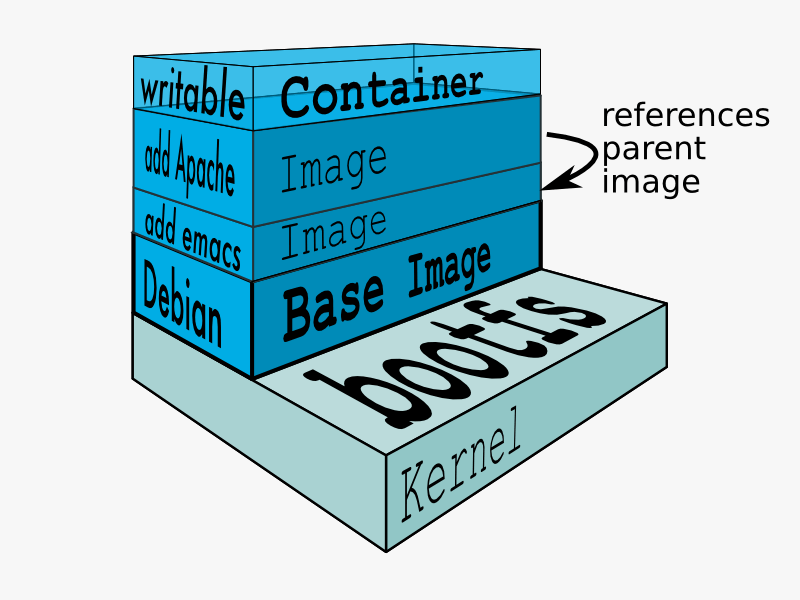

Docker relies heavily on the copy-on-write filesystem for it's image layers approach to work. Each image is usualy made of several layers which build on top of one another to get to the final state. These layers can also be re-used across images. For example image you have a base os image with the packages needed, then another layer with java and java dependencies and lastly a layer with your java based application. The advantage of this approach is you can reuse layers 1 and 2 for all your java apps so they occupy less space and work from the same source.

The major difference between a container and an image is the top writable layer. All writes to the container that add new or modify existing data are stored in this writable layer. When the container is deleted, the writable layer is also deleted. The underlying image remains unchanged.

Because each container has its own writable container layer, and all changes are stored in this container layer, multiple containers can share access to the same underlying image and yet have their own data state. The diagram below shows multiple containers sharing the same Ubuntu 15.04 image:

Inline-style:

Docker uses storage drivers to manage the contents of the image layers and the writable container layer. Each storage driver handles the implementation differently, but all drivers use stackable image layers and the copy-on-write (CoW) strategy.

Kubernetes components can be grouped in two categories, master components and node components.

The Kubernetes control plane is split into a set of components, which can all run on a single master node, or can be replicated in order to support high-availability clusters, or can even be run on Kubernetes itself (AKA self-hosted).

Kubernetes provides a REST API supporting primarily CRUD operations on (mostly) persistent resources, which serve as the hub of its control plane. Kubernetes’s API provides IaaS-like container-centric primitives such as Pods, Services, and Ingress, and also lifecycle APIs to support orchestration (self-healing, scaling, updates, termination) of common types of workloads, such as ReplicaSet (simple fungible/stateless app manager), Deployment (orchestrates updates of stateless apps), Job (batch), CronJob (cron), DaemonSet (cluster services), and StatefulSet (stateful apps). We deliberately decoupled service naming/discovery and load balancing from application implementation, since the latter is diverse and open-ended.

Both user clients and components containing asynchronous controllers interact with the same API resources, which serve as coordination points, common intermediate representation, and shared state. Most resources contain metadata, including labels and annotations, fully elaborated desired state (spec), including default values, and observed state (status).

Controllers work continuously to drive the actual state towards the desired state, while reporting back the currently observed state for users and for other controllers.

While the controllers are level-based to maximize fault tolerance, they typically watch for changes to relevant resources in order to minimize reaction latency and redundant work. This enables decentralized and decoupled choreography-like coordination without a message bus.

The following master components are available on Kubernetes:

- kube-apiserver. kube-apiserver exposes the Kubernetes API. It is the front-end for the Kubernetes control plane. It is designed to scale horizontally – that is, it scales by deploying more instances.

- etcd - etcd is used as Kubernetes’ backing store. All cluster data is stored here. Always have a backup plan for etcd’s data for your Kubernetes cluster.

- kube-controller-manager. kube-controller-manager runs controllers, which are the background threads that handle routine tasks in the cluster. Logically, each controller is a separate process, but to reduce complexity, they are all compiled into a single binary and run in a single process.

These controllers include:

-

Node Controller: Responsible for noticing and responding when nodes go down.

-

Replication Controller: Responsible for maintaining the correct number of pods for every replication controller object in the system.

-

Endpoints Controller: Populates the Endpoints object (that is, joins Services & Pods).

-

Service Account & Token Controllers: Create default accounts and API access tokens for new namespaces.

-

cloud-controller-manager. cloud-controller-manager runs controllers that interact with the underlying cloud providers. The cloud-controller-manager binary is an alpha feature introduced in Kubernetes release 1.6. cloud-controller-manager runs cloud-provider-specific controller loops only. You must disable these controller loops in the kube-controller-manager. You can disable the controller loops by setting the –cloud-provider flag to external when starting the kube-controller-manager.

cloud-controller-manager allows cloud vendors code and the Kubernetes core to evolve independent of each other. In prior releases, the core Kubernetes code was dependent upon cloud-provider-specific code for functionality. In future releases, code specific to cloud vendors should be maintained by the cloud vendor themselves, and linked to cloud-controller-manager while running Kubernetes. The following controllers have cloud provider dependencies:

-

Node Controller: For checking the cloud provider to determine if a node has been deleted in the cloud after it stops responding

-

Route Controller: For setting up routes in the underlying cloud infrastructure

-

Service Controller: For creating, updating and deleting cloud provider load balancers

-

Volume Controller: For creating, attaching, and mounting volumes, and interacting with the cloud provider to orchestrate volumes

-

kube-scheduler. kube-scheduler watches newly created pods that have no node assigned, and selects a node for them to run on.

-

addons. Addons are pods and services that implement cluster features. The pods may be managed by Deployments, ReplicationControllers, and so on. Namespaced addon objects are created in the kube-system namespace. Addon manager creates and maintains addon resources.

-

DNS. While the other addons are not strictly required, all Kubernetes clusters should have cluster DNS, as many examples rely on it. Cluster DNS is a DNS server, in addition to the other DNS server(s) in your environment, which serves DNS records for Kubernetes services. Containers started by Kubernetes automatically include this DNS server in their DNS searches.

-

Web UI (Dashboard). Dashboard is a general purpose, web-based UI for Kubernetes clusters. It allows users to manage and troubleshoot applications running in the cluster, as well as the cluster itself.

-

Container Resource Monitoring. Container Resource Monitoring records generic time-series metrics about containers in a central database, and provides a UI for browsing that data.

-

Cluster-level Logging. A Cluster-level logging mechanism is responsible for saving container logs to a central log store with search/browsing interface.

The API server serves up the Kubernetes API. It is intended to be a relatively simple server, with most/all business logic implemented in separate components or in plug-ins. It mainly processes REST operations, validates them, and updates the corresponding objects in etcd (and perhaps eventually other stores). Note that, for a number of reasons, Kubernetes deliberately does not support atomic transactions across multiple resources. Additionally, the API server acts as the gateway to the cluster. By definition, the API server must be accessible by clients from outside the cluster, whereas the nodes, and certainly containers, may not be. Clients authenticate the API server and also use it as a bastion and proxy/tunnel to nodes and pods (and services).

The API Server is the central management entity and the only component that directly talks with the distributed storage component etcd. It provides the following core functionality:

- Serves the Kubernetes API, used cluster-internally by the worker nodes as well as externally by kubectl

- Proxies cluster components such as the Kubernetes UI

- Allows the manipulation of the state of objects, for example pods and services

- Persists the state of objects in a distributed storage (etcd)

The Kubernetes API is a HTTP API with JSON as its primary serialization schema, however it also supports Protocol Buffers, mainly for cluster-internal communication. For extensibility reasons Kubernetes supports multiple API versions at different API paths, such as /api/v1 or /apis/extensions/v1beta1. Different API versions imply different levels of stability and support:

- Alpha level, for example v1alpha1 is disabled by default, support for a feature may be dropped at any time without notice and should only be used in short-lived testing clusters.

- Beta level, for example v2beta3, is enabled by default, means that the code is well tested but the semantics of objects may change in incompatible ways in a subsequent beta or stable release.

- Stable level, for example, v1 will appear in released software for many subsequent versions.

Let’s now have a look at how the HTTP API space is constructed. At the top level we distinguish between the core group (everything below /api/v1, for historic reasons under this path and not under /apis/core/v1), the named groups (at path /apis/$NAME/$VERSION) and system-wide entities such as /metrics. A part of the HTTP API space (based on v1.5) is shown in the following:

Going forward we’ll be focusing on a concrete example: batch operations. In Kubernetes 1.5, two versions of batch operations exist: /apis/batch/v1 and /apis/batch/v2alpha1, exposing different sets of entities that can be queried and manipulated.

Now we turn our attention to an exemplary interaction with the API (we are using Minishift and the proxy command oc proxy –port=8080 here to get direct access to the API):

$ curl http://127.0.0.1:8080/apis/batch/v1

{

"kind": "APIResourceList",

"apiVersion": "v1",

"groupVersion": "batch/v1",

"resources": [

{

"name": "jobs",

"namespaced": true,

"kind": "Job"

},

{

"name": "jobs/status",

"namespaced": true,

"kind": "Job"

}

]

}

And further, using the new, alpha version:

$ curl http://127.0.0.1:8080/apis/batch/v2alpha1

{

"kind": "APIResourceList",

"apiVersion": "v1",

"groupVersion": "batch/v2alpha1",

"resources": [

{

"name": "cronjobs",

"namespaced": true,

"kind": "CronJob"

},

{

"name": "cronjobs/status",

"namespaced": true,

"kind": "CronJob"

},

{

"name": "jobs",

"namespaced": true,

"kind": "Job"

},

{

"name": "jobs/status",

"namespaced": true,

"kind": "Job"

},

{

"name": "scheduledjobs",

"namespaced": true,

"kind": "ScheduledJob"

},

{

"name": "scheduledjobs/status",

"namespaced": true,

"kind": "ScheduledJob"

}

]

}

In general the Kubernetes API supports create, update, delete, and retrieve operations at the given path via the standard HTTP verbs POST, PUT, DELETE, and GET with JSON as the default payload.

Most API objects make a distinction between the specification of the desired state of the object and the status of the object at the current time. A specification is a complete description of the desired state and is persisted in stable storage.

-

Terminology

After this brief overview of the API Server and the HTTP API space and its properties, we now define the terms used in this context more formally. Primitives like pods, services, endpoints, deployment, etc. make up the objects of the Kubernetes type universe. We use the following terms:

Kind is the type of an entity. Each object has a field Kind which tells a client—such as kubectl or oc—that it represents, for example, a pod:

apiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: webserver spec: containers: - name: nginx image: nginx:1.9 ports: - containerPort: 80There are three categories of Kinds:

- Objects represent a persistent entity in the system. An object may have multiple resources that clients can use to perform specific actions. Examples: Pod and Namespace.

- Lists are collections of resources of one or more kinds of entities. Lists have a limited set of common metadata. Examples: PodLists and NodeLists.

- Special purpose kinds are for example used for specific actions on objects and for non-persistent entities such as /binding or /status, discovery uses APIGroup and APIResource, error results use Status, etc.

API Group is a collection of Kinds that are logically related. For example, all batch objects like Job or ScheduledJob are in the batch API Group.

Version. Each API Group can exist in multiple versions. For example, a group first appears as v1alpha1 and is then promoted to v1beta1 and finally graduates to v1. An object created in one version (e.g. v1beta1) can be retrieved in each of the supported versions (for example as v1). The API server does lossless conversion to return objects in the requested version.

Resource is the representation of a system entity sent or retrieved as JSON via HTTP; can be exposed as an individual resource (such as …/namespaces/default) or collections of resources (like …/jobs).

An API Group, a Version and a Resource (GVR) uniquely defines a HTTP path:

More precisely, the actual path for jobs is /apis/batch/v1/namespaces/$NAMESPACE/jobs because jobs are not a cluster-wide resource, in contrast to, for example, node resources. For brevity, we omit the $NAMESPACE segment of the paths throughout the post.

Note that Kinds may not only exist in different versions, but also in different API Groups simultaneously. For example, Deployment started as an alpha Kind in the extensions group and was eventually promoted to a GA version in its own group apps.k8s.io. Hence, to identify Kinds uniquely you need the API Group, the version and the kind name (GVK).

-

Request Flow and Processing

Now that we’ve reviewed the terminology used in the Kubernetes API we move on to how API requests are processed. The API lives in k8s.io/pkg/api and handles requests from within the cluster as well as to clients outside of the cluster.

So, what actually happens now when an HTTP request hits the Kubernetes API? On a high level, the following interactions take place:

- The HTTP request is processed by a chain of filters registered in DefaultBuildHandlerChain() (see config.go) that applies an operation on it (see below for more details on the filters). Either the filter passes and attaches respective infos to ctx.RequestInfo, such as authenticated user or returns an appropriate HTTP response code.

- Next, the multiplexer (see container.go) routes the HTTP request to the respective handler, depending on the HTTP path.

- The routes (as defined in routes/*) connect handlers with HTTP paths.

- The handler, registered per API Group (see groupversion.go and installer.go) takes the HTTP request and context (like user, rights, etc.) and delivers the requested object from storage.

-

Additional Reading

From your *nix operating system you know that /etc is used to store config data and, in fact, the name etcd is inspired by this, adding the “d” for distributed. Any distributed system will likely need something like etcd to store data about the state of the system, enabling it to retrieve the state in a consistent and reliable fashion. To coordinate the data access in a distributed setup, etcd uses the Raft protocol. In many ways etcd is similar to zookeeper as they are both used for cluster coordination. You can implement on top of both different strategies like distributed lock or service discovery. Both of these are not designed to store lots of data. In our production systems we run etcd in nodes of 3 (etcd is deployed with 2n+1 peer services to ensure quorum in case of partition), but it can also be run as a single node for testing and development environments. To interact with etcd you can use their command line client etcdctl. You can also use plain `curl` to interact with it. A small guide on how to interact with it is available here.

Conceptually, the data model etcd supports is that of key-value store. In etcd2 the keys formed a hierarchy and with the introduction of etcd3 this has turned into a flat model, while maintaining backwards compatibility concerning hierarchical keys.

Using a containerized version of etcd, we can create the above tree and then retrieve it as follows:

$ docker run --rm -d -p 2379:2379 \

--name test-etcd3 quay.io/coreos/etcd:v3.1.0 /usr/local/bin/etcd \

--advertise-client-urls http://0.0.0.0:2379 --listen-client-urls http://0.0.0.0:2379

$ curl localhost:2379/v2/keys/foo -XPUT -d value="some value"

$ curl localhost:2379/v2/keys/bar/this -XPUT -d value=42

$ curl localhost:2379/v2/keys/bar/that -XPUT -d value=take

$ http localhost:2379/v2/keys/?recursive=true

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Length: 327

Content-Type: application/json

Date: Tue, 06 Jun 2017 12:28:28 GMT

X-Etcd-Cluster-Id: 10e5e39849dab251

X-Etcd-Index: 6

X-Raft-Index: 7

X-Raft-Term: 2

{

"action": "get",

"node": {

"dir": true,

"nodes": [

{

"createdIndex": 4,

"key": "/foo",

"modifiedIndex": 4,

"value": "some value"

},

{

"createdIndex": 5,

"dir": true,

"key": "/bar",

"modifiedIndex": 5,

"nodes": [

{

"createdIndex": 5,

"key": "/bar/this",

"modifiedIndex": 5,

"value": "42"

},

{

"createdIndex": 6,

"key": "/bar/that",

"modifiedIndex": 6,

"value": "take"

}

]

}

]

}

}

To get a real feel for ETCD you can use their online simulator available at http://play.etcd.io/play. Now that we’ve established how etcd works in principle, let’s move on to the subject of how etcd is used in Kubernetes.

-

Cluster state in etcd

In Kubernetes, etcd is an independent component of the control plane. Up to Kubernetes 1.5.2, we used etcd2 and from then on switched to etcd3. Note that in Kubernetes 1.5.x etcd3 is still used in v2 API mode and going forward this is changing to the v3 API, including the data model used. From a developer’s point of view this doesn’t have direct implications, because the API Server takes care of abstracting the interactions away—compare the storage backend implementation for v2 vs. v3. However, from a cluster admin’s perspective, it’s relevant to know which etcd version is used, as maintenance tasks such as backup and restore need to be handled differently.

You can influence the way the API Server is using etcd via a number of options at start-up time; also, note that the output below was edited to highlight the most important bits:

$ kube-apiserver -h ... --etcd-cafile string SSL Certificate Authority file used to secure etcd communication. --etcd-certfile string SSL certification file used to secure etcd communication. --etcd-keyfile string SSL key file used to secure etcd communication. ... --etcd-quorum-read If true, enable quorum read. --etcd-servers List of etcd servers to connect with (scheme://ip:port) … ...Kubernetes stores its objects in etcd either as a JSON string or in Protocol Buffers (“protobuf” for short) format. Let’s have a look at a concrete example: We launch a pod webserver in namespace apiserver-sandbox :

$ cat pod.yaml apiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: webserver spec: containers: - name: nginx image: tomaskral/nonroot-nginx ports: - containerPort: 80 $ kubectl create -f pod.yaml $ etcdctl ls / /kubernetes.io /openshift.io $ etcdctl get /kubernetes.io/pods/apiserver-sandbox/webserver { "kind": "Pod", "apiVersion": "v1", "metadata": { "name": "webserver", ...So, how does the object payload end up in etcd, starting from kubectl create -f pod.yaml?

- A client such as kubectl provides an desired object state, for example, YAML in version v1.

- kubectl converts the YAML into JSON to send it over the wire.

- Between different versions of the same kind, the API server can perform a lossless conversion leveraging annotations to store information that cannot be expressed in older API versions.

- The API Server turns the input object state into a canonical storage version, depending on the API Server version itself, usually the newest stable one, for example, v1.

- Last but not least comes actual storage process in etcd, at a certain key, into a value with the encoding to JSON or protobuf.

kube-controller-manager runs controllers, which are the background threads that handle routine tasks in the cluster. Logically, each controller is a separate process, but to reduce complexity, they are all compiled into a single binary and run in a single process.

These controllers include:

- Node Controller: Responsible for noticing and responding when nodes go down.

- Replication Controller: Responsible for maintaining the correct number of pods for every replication controller object in the system.

- Endpoints Controller: Populates the Endpoints object (that is, joins Services & Pods).

- Service Account & Token Controllers: Create default accounts and API access tokens for new namespaces.

-

Node Controller

The node controller is a Kubernetes master component which manages various aspects of nodes. The node controller has multiple roles in a node’s life. The first is assigning a CIDR block to the node when it is registered (if CIDR assignment is turned on). The second is keeping the node controller’s internal list of nodes up to date with the cloud provider’s list of available machines. When running in a cloud environment, whenever a node is unhealthy, the node controller asks the cloud provider if the VM for that node is still available. If not, the node controller deletes the node from its list of nodes. The third is monitoring the nodes’ health. The node controller is responsible for updating the NodeReady condition of NodeStatus to ConditionUnknown when a node becomes unreachable (i.e. the node controller stops receiving heartbeats for some reason, e.g. due to the node being down), and then later evicting all the pods from the node (using graceful termination) if the node continues to be unreachable. (The default timeouts are 40s to start reporting ConditionUnknown and 5m after that to start evicting pods.) The node controller checks the state of each node every –node-monitor-period seconds. In Kubernetes 1.4, the logic of the node controller was updated to better handle cases when a large number of nodes have problems with reaching the master (e.g. because the master has networking problem). Starting with 1.4, the node controller will look at the state of all nodes in the cluster when making a decision about pod eviction. In most cases, node controller limits the eviction rate to –node-eviction-rate (default 0.1) per second, meaning it won’t evict pods from more than 1 node per 10 seconds. The node eviction behavior changes when a node in a given availability zone becomes unhealthy. The node controller checks what percentage of nodes in the zone are unhealthy (NodeReady condition is ConditionUnknown or ConditionFalse) at the same time. If the fraction of unhealthy nodes is at least –unhealthy-zone-threshold (default 0.55) then the eviction rate is reduced: if the cluster is small (i.e. has less than or equal to –large-cluster-size-threshold nodes - default 50) then evictions are stopped, otherwise the eviction rate is reduced to –secondary-node-eviction-rate (default 0.01) per second. The reason these policies are implemented per availability zone is because one availability zone might become partitioned from the master while the others remain connected. If your cluster does not span multiple cloud provider availability zones, then there is only one availability zone (the whole cluster). A key reason for spreading your nodes across availability zones is so that the workload can be shifted to healthy zones when one entire zone goes down. Therefore, if all nodes in a zone are unhealthy then node controller evicts at the normal rate –node-eviction-rate. The corner case is when all zones are completely unhealthy (i.e. there are no healthy nodes in the cluster). In such case, the node controller assumes that there’s some problem with master connectivity and stops all evictions until some connectivity is restored. Starting in Kubernetes 1.6, the NodeController is also responsible for evicting pods that are running on nodes with NoExecute taints, when the pods do not tolerate the taints. Additionally, as an alpha feature that is disabled by default, the NodeController is responsible for adding taints corresponding to node problems like node unreachable or not ready. See this documentation for details about NoExecute taints and the alpha feature. Starting in version 1.8, the node controller can be made responsible for creating taints that represent Node conditions. This is an alpha feature of version 1.8.

-

Replication Controller

A ReplicationController ensures that a specified number of pod replicas are running at any one time. In other words, a ReplicationController makes sure that a pod or a homogeneous set of pods is always up and available. If there are too many pods, the ReplicationController terminates the extra pods. If there are too few, the ReplicationController starts more pods. Unlike manually created pods, the pods maintained by a ReplicationController are automatically replaced if they fail, are deleted, or are terminated. For example, your pods are re-created on a node after disruptive maintenance such as a kernel upgrade. For this reason, you should use a ReplicationController even if your application requires only a single pod. A ReplicationController is similar to a process supervisor, but instead of supervising individual processes on a single node, the ReplicationController supervises multiple pods across multiple nodes. ReplicationController is often abbreviated to “rc” or “rcs” in discussion, and as a shortcut in kubectl commands. A simple case is to create one ReplicationController object to reliably run one instance of a Pod indefinitely. A more complex use case is to run several identical replicas of a replicated service, such as web servers.

-

Endpoints controller

Kubernetes Pods are mortal. They are born and when they die, they are not resurrected. ReplicationControllers in particular create and destroy Pods dynamically (e.g. when scaling up or down or when doing rolling updates). While each Pod gets its own IP address, even those IP addresses cannot be relied upon to be stable over time. This leads to a problem: if some set of Pods (let’s call them backends) provides functionality to other Pods (let’s call them frontends) inside the Kubernetes cluster, how do those frontends find out and keep track of which backends are in that set? Enter Services. A Kubernetes Service is an abstraction which defines a logical set of Pods and a policy by which to access them - sometimes called a micro-service. The set of Pods targeted by a Service is (usually) determined by a Label Selector (see below for why you might want a Service without a selector). As an example, consider an image-processing backend which is running with 3 replicas. Those replicas are fungible - frontends do not care which backend they use. While the actual Pods that compose the backend set may change, the frontend clients should not need to be aware of that or keep track of the list of backends themselves. The Service abstraction enables this decoupling. For Kubernetes-native applications, Kubernetes offers a simple Endpoints API that is updated whenever the set of Pods in a Service changes. For non-native applications, Kubernetes offers a virtual-IP-based bridge to Services which redirects to the backend Pods.

Endpoints are managed by the endpoints controller.

The Kubernetes scheduler is a policy-rich, topology-aware, workload-specific function that significantly impacts availability, performance, and capacity. The scheduler needs to take into account individual and collective resource requirements, quality of service requirements, hardware/software/policy constraints, affinity and anti-affinity specifications, data locality, inter-workload interference, deadlines, and so on. Workload-specific requirements will be exposed through the API as necessary.

-

The scheduling algorithm