There are many types of elections. We need a base set of data that shows how these different types of elections are handled in an ElectionGuard end-to-end verifiable election (or ballot comparison audits).

We worked with InfernoRed, VotingWorks, and Dan Wallach of Rice University (thanks folks!) to develop a set of conventions, tests, and sample data (based on a starting dataset sample from the Center for Civic Design) that demonstrate how to encode the information necessary to conduct an election into a format that ElectionGuard can use. The election terms and structure are based whenever possible on the NIST SP-1500-100 Election Results Common Data Format Specification (PDF) and the Civics Common Standard Data Specification. The information captured by the NIST standard is codified into an election manifest that defines common elements when conducting an election, such as locations, candidates, parties, contests, and ballot styles.

ElectionGuard uses the data contained in the Election Manifest to associate ballots with specific ballot styles and to verify the accuracy of data at different stages of the election process. Note that not all of the data contained in the Election Manifest impacts the computations of tallies and zero-knowledge proofs used in the published election data that demonstrates end-to-end verifiability; however it is important to include as much data as possible in order to distinguish one election from another. With a well-defined Election Manifest, improperly formatted ballot encryption requests will fail with error messages at the moment of initial encryption; the enforcement of any logic or behavior to prevent overvoting or other malformed ballot submissions are handled by the encrypting device, not ElectionGuard.

In addition, since json files do not accommodate comments, all notations and exceptions are documented in this readme.

Elections are characterized into types by NIST as shown in the table below:

| election type | description |

|---|---|

| general | For an election held typically on the national day for elections. |

| partisan-primary-closed | For a primary election that is for a specific party where voter eligibility is based on registration. |

| partisan-primary-open | For a primary election that is for a specific party where voter declares desired party or chooses in private. |

| primary | For a primary election without a specified type, such as a nonpartisan primary. |

| runoff | For an election to decide a prior contest that ended with no candidate receiving a majority of the votes. |

| special | For an election held out of sequence for special circumstances, for example, to fill a vacated office. |

| other | Used when the election type is not listed in this enumeration. If used, include a specific value of the OtherType element. |

We present two sample manifests: general and partisan-primary-closed. The core distinction between the two samples is the role of party: in general elections, voters can choose to vote for candidates from any party in a contest, regardless of party affiliation. In partisan primaries, voters can only vote in contests germane to their party declaration or affiliation. As such, special, runoff, and primary election types will follow the general pattern, and partisan-primary-open will follow the partisan-primary-closed pattern. Open primary elections can follow either pattern as determined by their governing rules and regulations. (As noted above, ElectionGuard expects properly-formed ballots; e.g., it would error and fail to encrypt a ballot in an open-primary-closed election if a contest with an incorrect party affiliation were submitted (as indicated by the ).)

At least in the United States, many complications are introduced by voting simultaneously on election contests that apply in specific geographies and jurisdictions. For example, a single election could include contests for congress, state assembly, school, and utility districts, each with their own geographic boundaries, many that do not respect town or county lines. The ElectionGuard Election Manifest data format is flexible to accommodate most situations, but it is usually up to the election commission and the external system to determine what each component of the manifest actually means.

In the following examples, we will work through the process of defining different election types at a high level and describe the process of building the election manifest.

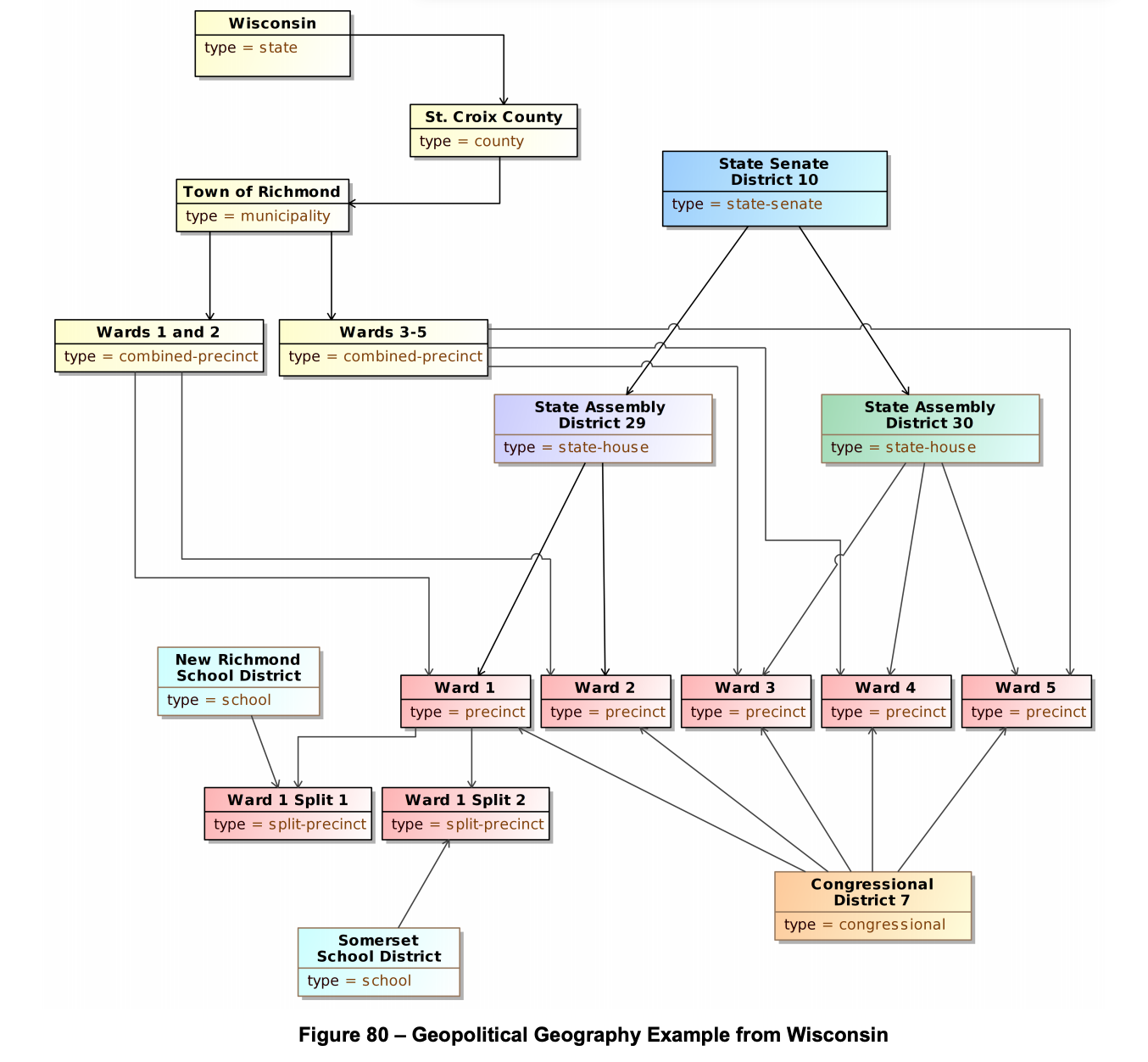

Each election can be thought of as a list of contests that are relevant to a certain group of people in a specific place. In order to determine who is supposed to vote on which contests, we first need to define the geographic jurisdictions where the election is taking place. The NIST Guidelines present an excellent discussion of the geographic interplay of different contests. The diagram from page 12 is presented below.

As the diagram shows, congressional, state assembly, school district and other geographic boundaries project onto towns and municipalities in different ways. Elections manage this complexity by creating unique ballot styles that present to voters only the contests that pertain to them. Different jurisdictions use terms such as wards, precincts, and districts to describe the areas of overlap that guide ballot style creation. We will use precinct but ward and district could be used instead.

In most cases, a resident of a specific precinct or location will expect to see a certain list of contests that are relevant to them. A contest is a specific collection of available choices (selections) from which the voter may choose some subset. For the ElectionGuard Election Manifest, each possible selection in a contest must be associated with a candidate, even for Referendum-style contests. If a contest also supports write-in values, then a write-in candidate is also defined. Candidates may also be associated with specific parties, but this is not required for all election types.

To help disambiguate, let's explore an example.

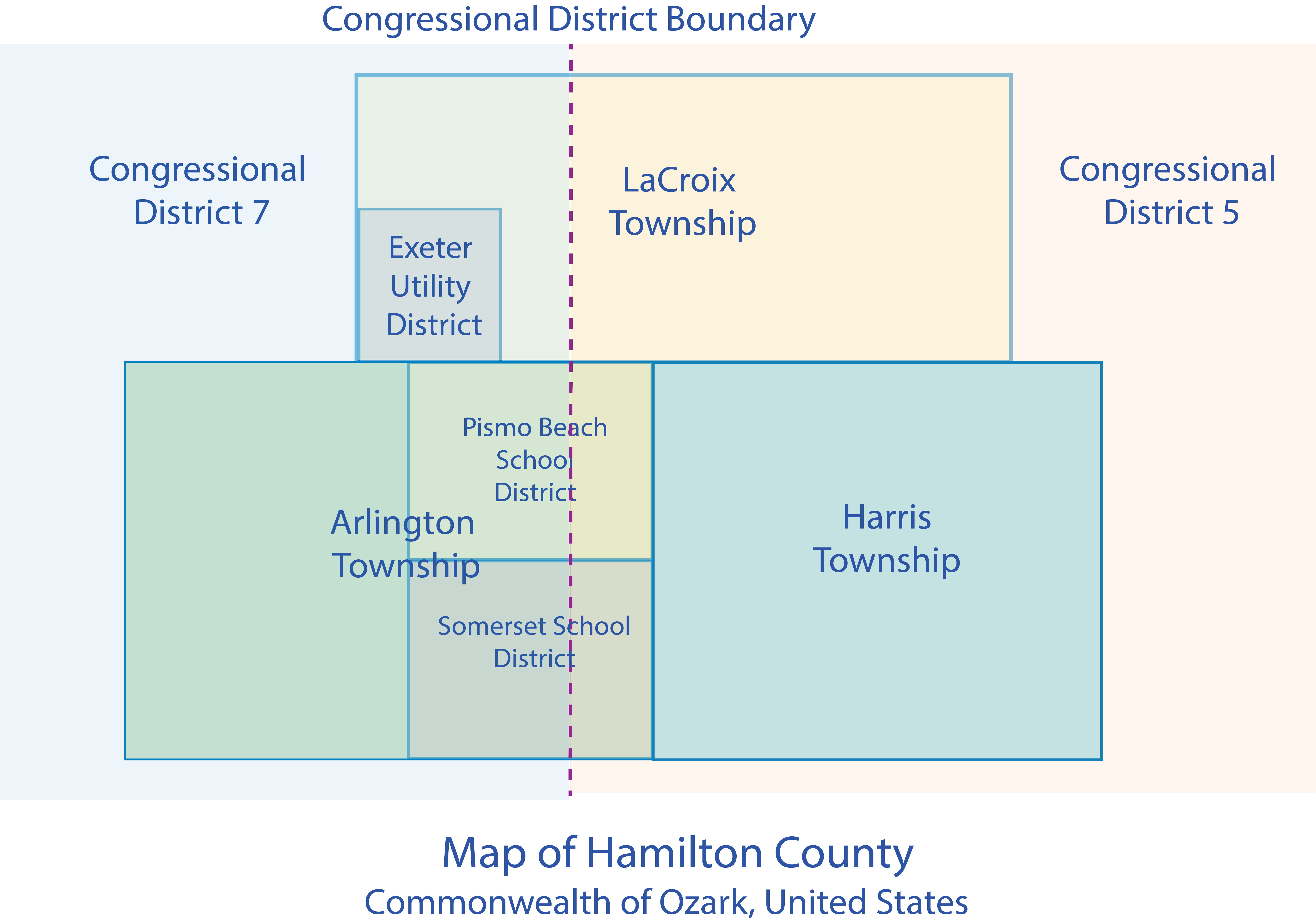

Hamilton County includes 3 townships: LaCroix, Arlington, Harris. The town of LaCroix also has a utility district that comprises its own precinct for special referendums. Arlington has two distinct school districts. The county is also split into two congressional districts, district 5 and district 7. Harris township is entirely within Congressional District 5, but both LaCroix and Arlington are split between congressional districts 5 and 7.

The Election Manifest includes an array of objects called geopoliticalUnits (a.k.a. gpUnit). Each Geopolitical Unit must include the following fields:

- objectId - a unique identifier for the gpUnit. This value is used to map a contest to a specific jurisdiction

- name - the friendly name of the gp Unit

- type - they type of jurisdiction (one of the Reporting Unit Types)

- contact information - the contact info for the geopolitical unit

Geopolitical units are polygons on a map represented by legal jurisdictions. In our example Election Manifest for hamilton County, there is one geopolitical unit for each jurisdictional boundary in the image above:

- Hamilton County

- Congressional District 5

- congressional District 7

- LaCroix Township

- Exeter Utility District (within LaCroix Township)

- Harris Township

- Arlington Township

- Pismo Beach School District (within Arlington Township)

- Somerset School District (within Arlington Township)

When defining the geopolitical units for an election, we define all of the possible geopolitical units for an election; even if there are no contests for a specific jurisdiction. This way, if contests are added or removed during the setup phase, you do not also have to remember to update the list of geopolitical units. Alternatively, you can define only the GP Units for which there are contests.

A general election will occur in Hamilton County. The county is voting along with the rest of the province, and the county is responsible for tabulating its own election results. This means that the Election Scope is defined at the county level.

For the general election, the following sets of contests (and associated geographic boundaries) obtain:

- The National Contests - President and Vice President. This contest demonstrates a "vote for the ticket" and allows write-ins

- Province Contests - Governor - this contest demonstrates a long list of candidate names

- Congressional Contests - Congress Districts 5 and 7 - these contests demonstrate how to split a district using multiple ballot styles

- Township Contests - Retain Chief Justice - This contest demonstrates a contest that applies to a specific town whose boundaries are split across multiple ballot styles

- School District Contests - School Board - these contests demonstrate contests with multiple selections (n-of-m) and allow write-ins School Board, and Utility district referendum to show ballot style splits

- Utility District Contest - Utility District - This contest demonstrates a referendum-style contest with long descriptions and display language translation into Spanish

Each contest must be associated with exactly ONE electoralDistrictId. The electoralDistrictId field on the contest is populated with the objectId of the associated Geopolitical Unit (e.g. the Contest congress-district-7-contest has the electoralDistrictId congress-district-7

Each contest must also define a sequenceOrder. the sequence order is an indexing mechanism used internally. It is not the sequence that the contests are displayed to the user. The order in which contests are displayed to the user is up to the implementing application.

A ballot style is the set of contests that a specific voter should see on their ballot for a given location. The ballot style is associated to the set of geopolitical units relevant to a specific point on a map. Since each contest is also associated with a geopolitical unit, a mapping is created between a point on a map and the contests that are relevant to that point.

For instance, a voter that lives in the Exeter Utility District should see contests that are relevant to Congressional District 7, LaCroix Township and the Exeter Utility District.

| Geopolitical Units are overlapping polygons, and ballot styles are the list of polygons relevant to a specific point on the map.

Similar to Geopolitical Units, we define all of the possible ballot styles for an election in our example, even if there are no contests specific to a ballot style. This is subjective and the behavior may be different for the integrating system:

- Congressional District 7 Outside Any Township

- Congressional District 7 LaCroix Township

- Congressional District 7 LaCroix Township Exeter Utility District

- Congressional District 7 Arlington Township

- Congressional District 7 Arlington Township Pismo Beach School district

- Congressional District 7 Arlington Township Somerset School district

- Congressional District 5 Outside Any Township

- Congressional District 5 LaCroix Township

- Congressional District 5 Harris Township

- Congressional District 5 Arlington Township Pismo Beach School district

- Congressional District 5 Arlington Township Somerset School district

By defining all of the possible ballot styles and all of the possible geopolitical units, we ensure that if a contest is added or removed, we only have to make sure the contest is correct. We do not have to modify the list of geopolitical units or ballot styles.

The relationship between a ballot style and the contests that are displayed on it are subjective to the implementing application. This example is just one way to define this relationship that is purposefully verbose. For instance, in our example we define a geopolitical unit as a set of overlapping polygons, and a ballot style as the intersection of those polygons at a specific point. This is a top-down approach. Alternatively, we could have defined a geopolitical unit as the intersection area of those polygons and mapped one ballot style to each geopolitical unit 1 to 1.

for instance, instead of defining a single GP Unit each for:

- Congressional District 5,

- Congressional District 7,

- LaCroix Township,

- Exeter Utility district, etc;

we could have instead defined the GP Units as:

- Congressional District 5 No Township

- Congressional District 7 No Township

- Congressional District 5 inside LaCroix

- Congressional District 5 Inside LaCroix and Exeter, etc.

Then, instead of each Ballot Style having multiple GP Units, each ballot style would have applied to exactly one GP Unit.

When the election Manifest is loaded into ElectionGuard, its validity is checked semantically against the data format required to conduct an ElectionGuard Election. Specifically, we check that:

- Each Geopolitical Unit has a unique objectId

- Each Ballot Style maps to at least one valid Geopolitical Unit

- Each Party has a unique objectId

- Each Candidate either does not have a party, or is associated with a valid party

- Each Contest has a unique Sequence Order

- Each Contest is associated with exactly one valid Geopolitical Unit

- Each Contest has a valid number of Selections for the number of seats in the contest

- Each Selection on each Contest is associated with a valid Candidate

as long as the election manifest format matches the validation criteria, the election can proceed as an ElectionGuard election.

Q: What if my ballot styles are not associated with geopolitical units?

A: There are a few ways to handle this. In most cases, you can simply map the ballot style 1 to 1 to the geopolitical unit. for instance, if ballot-style-1 includes contest-1 then you may create geopolitical-unit-1 and associate both the ballot style and the contest to that geopolitical unit.

This documentation is under review and subject to change. Please do not hesitate to open a github issue if you have questions, or find errors or omissions.