IMPORTANT NOTE: This documentation only applies to GrainSizeTools v2.0+ Please check your script version before using this tutorial. You will be able to reproduce all the results shown in this tutorial using the dataset provided with the script, the file

data_set.txt

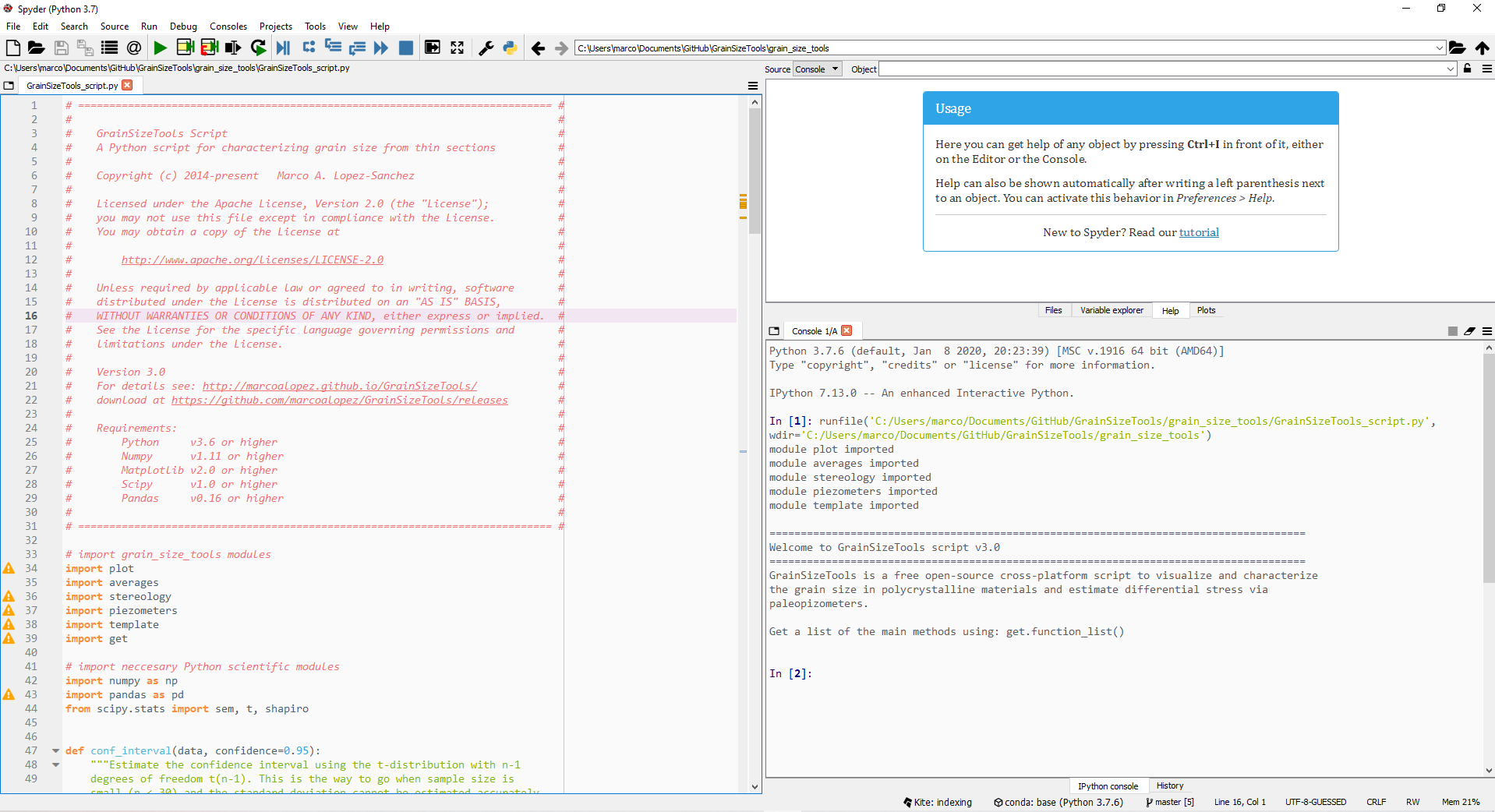

First of all, make sure you have the latest version of the GrainSizeTools script and a Python scientific distribution installed (see requirements for more details). Launch the Spyder -if you installed the Anaconda or miniconda package- or the Canopy IDE -if you installed the Enthought package- and then open the GrainSizeTools_script.py file using File>Open. The script will appear in the code editor as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. The Spyder integrated development environment (IDE) showing the editor, the Python shell or console, and the file explorer. Canopy and Spyder are both MATLAB-like IDEs optimized for numerical computing and data analysis with Python. They also provide a variable explorer or a history log among other interesting features.

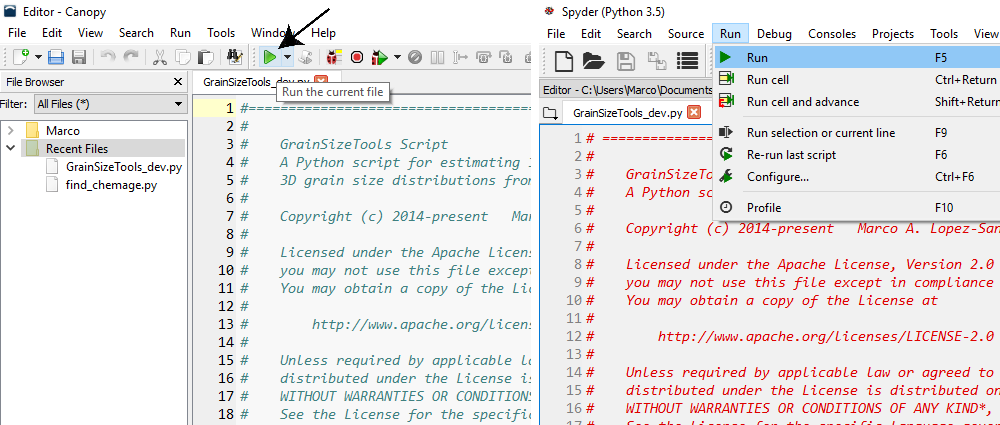

Before interacting with the script it is necessary to run it. Then, just click on the green "play" icon in the tool bar or go to Run>Run file in the menu bar (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Running the script in the Enthought's Canopy (left) and Spyder (right) IDEs.

The following text will appear in the console:

======================================================================================

Welcome to GrainSizeTools script v2.0.3

======================================================================================

GrainSizeTools is a free open-source cross-platform script to visualize and characterize

the grain size in polycrystalline materials from thin sections and estimate differential

stresses via paleopizometers.

METHODS AVAILABLE

================== ==================================================================

List of functions Description

================== ==================================================================

area2diameter Estimate the equivalent circular diameter from area sections

calc_diffstress Estimate diff. stress from grain size using piezometers

calc_grain_size Estimate the apparent grain size and visualize their distribution

calc_shape Characterize the log shape of the actual grain size distribution

confidence_interval Estimate a robust confidence interval using the t-distribution

extract_column Extract data from tabular-like text files (txt, csv or xlsx)

Saltykov Estimate the actual grain size distribution via the Saltykov method

test_lognorm Test the lognormality of the distribution using a q-q plot

================== ==================================================================

You can get more information about the methods in the following ways:

(1) Typing help plus the name of the function e.g. help(calc_shape)

(2) In the Spyder IDE by writing the name of the function and clicking Ctrl + I

(3) Visiting the script documentation at https://marcoalopez.github.io/GrainSizeTools/

(4) Get a list of the methods available: print(functions_list)

Once you see this, all the tools implemented in the GrainSizeTools script will be available by typing some commands in the shell as will be explained below.

The script is organized in a modular way using different Python files and functions, both with the aim of helping to modify, reuse, and extend the code if needed. Since version 2.0, the script consist of four different Python files that must be in the same directory. These are the GrainSizeTools.py, the plots.py, the tools.py, and the piezometers.py files. Within the files there are several Python functions. A Python function looks like this in the editor:

def area2diameter(areas, correct_diameter=None):

""" Calculate the equivalent cirular diameter from sectional areas.

Parameters

----------

areas : array_like

the sectional areas of the grains

correct_diameter : None or positive scalar, optional

add the width of the grain boundaries to correct the diameters. If

correct_diameter is not declared no correction is considered.

Returns

-------

A numpy array with the equivalent circular diameters

"""

# calculate the equivalent circular diameter

diameters = 2 * sqrt(areas / np.pi)

# diameter correction adding edges (if applicable)

if correct_diameter is not None:

diameters += correct_diameter

return diametersTo sum up, the name following the Python keyword def, in this example area2diameter, is the name of the function. The sequence of names within the parentheses are the formal parameters of the function (i.e. the inputs) followed by a colon. In this case, the area2diameter function has two inputs, areas and correct_diameter. The first one corresponds with an array containing the areas of the grain profiles. The second parameter corresponds to a number that sometimes is required for correcting the size of the grains. Note that in this case the parameter is set to None by default and thus the parameter is optional. The text between the triple quotation marks provides information on the conditions that must be met by the user as well as the output obtained. This information can also be accessed from the console by using the command help() and specifying the name of the function within the parentheses or, in the Spyder IDE, by pressing Ctrl+I once you wrote the name of the function. Below, it is the code block or function body.

The names of the Python functions in the script are self-explanatory and each one has been implemented to perform a single task. Although there are a lot of functions within the script, we will only interact directly with a few, specifically the ones listed in the List of Functions: print(functions_list).

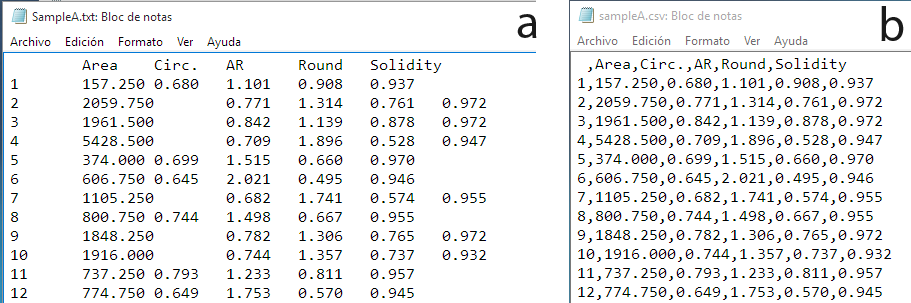

The first step is load the grain profile areas or the apparent diameters of the grains measured in a thin section. It is therefore assumed that this was previously done using the ImageJ, the MTEX toolbox, or any other software, and that the results were saved as a tabular-like file, either txt, csv, or xlsx (Fig. 3). If you do not know how to do this, then go to How to measure the grain profile areas with ImageJ or How to reconstruct the grains from SEM-EBSD data using the MTEX toolbox.

Figure 3. Tabular-like files generated by the ImageJ application. At left, the tab-separated txt file. At right, the csv (comma-separated) version.

When we apply image analysis in polycrystaline materials, we usually measure different features of the grains at once (Fig. 3). For the grain size analysis, we need to extract the data corresponding to the areas of the sections of the grains or, directly, the apparent diameters if they have been previously calculated as equivalent circular diameters. The script implements a function named extract_column for this. We invoke this function as follows:

>>> areas = extract_column()where areas is just a name, known as variable, in which the data extracted will be stored into memory. This will allow us to access and manipulate later the areas of the grain profiles using other functions. Almost any name can be used to create a variable in Python. As an example, if you want to load several datasets, you can name them areas1, areas2, my_data , diameters, and so on. In Python, variable names can contain upper and lowercase letters (the language is case-sensitive), digits and the special character _, but cannot start with a digit. Also, there are some special keywords reserved for the language (e.g. True, False, if, else, etc.), but do not worry about it, the console will highlight the word to warn you that this is a keyword.

The function extract_column uses by default the column name 'Area' , since it is the name used by the ImageJ application to store the areas of the grain profiles, but you can define any column name to extract as follows:

>>> areas = extract_column(col_name='areas')

>>> diameters = extract_column(col_name='eq_diameters')Once you press the Enter key, a new window will pop up showing a file selection dialog so that you can search and open the file that contains the dataset. Then, the function will automatically extract the information corresponding to the defined column and store them into a variable. To check that everything is ok, the shell will return the first and last rows of the dataset and the first and last values of the column extracted as follows:

>>> areas = extract_column()

Area Circ. Feret ... MinFeret AR Round Solidity

0 1 157.25 0.680 18.062 ... 13.500 1.101 0.908 0.937

1 2 2059.75 0.771 62.097 ... 46.697 1.314 0.761 0.972

2 3 1961.50 0.842 57.871 ... 46.923 1.139 0.878 0.972

3 4 5428.50 0.709 114.657 ... 63.449 1.896 0.528 0.947

4 5 374.00 0.699 29.262 ... 16.000 1.515 0.660 0.970

[5 rows x 11 columns]

Area Circ. Feret ... MinFeret AR Round Solidity

2656 2657 452.50 0.789 28.504 ... 22.500 1.235 0.810 0.960

2657 2658 1081.25 0.756 47.909 ... 31.363 1.446 0.692 0.960

2658 2659 513.50 0.720 32.962 ... 20.496 1.493 0.670 0.953

2659 2660 277.75 0.627 29.436 ... 17.002 1.727 0.579 0.920

2660 2661 725.00 0.748 39.437 ... 28.025 1.351 0.740 0.960

[5 rows x 11 columns]

column extracted:

Area = [ 157.25 2059.75 1961.5 ... 513.5 277.75 725. ]

n = 2661The data stored in any variable can be viewed at any time by invoking its name in the console and pressing the Enter key. Furthermore, both the Canopy and the Spyder IDEs have a specific variable explorer to visualize them.

The extract_column function also allows you to manually define the file path of the file (note that different inputs/parameters are comma-separated) as follows:

>>> areas = extract_column(file_path='data_set.txt', col_name='areas')👉 The

extract_columnfunction aims to simplify the task of extracting data for users with no previous programming experience in Python. If you are familiar with common Python scientific libraries, the natural way to interact with the data and the script is using the import tool implemented in the Spyder IDE and/or the Pandas library.

If you measured the areas of the grain profiles, then we need to convert them into apparent diameters via the equivalent circular diameter (ECD):

ECD = 2 * √(area / π)

This can be done directly in the console using

>>> diameters = 2 * np.sqrt(areas / np.pi)or using the area2diameter function

>>> diameters = area2diameter(areas)Note that in all the example above we define a new variable diameters to store the equivalent circular diameters. In some cases, we would need to correct the size of the grain profiles (Fig. 5). For this, you can add a new parameter in the area2diameter function

>>> diameters = area2diameter(areas, correct_diameter=0.5)and 0.5 will be added to each equivalent circular diameter. If the parameter correct_diameter is not declared within the function, as in the first example, it is assumed that no diameter correction is needed.

Figure 5. Example of correction of sizes in a grain boundary map. The image is a raster (pixel-based) showing the grain boundaries (in white) between three grains. The squares are the pixels of the image. The boundaries are two-three pixel wide. If, for example, each pixel corresponds to 1 micron, we will need to add 2.5 microns to the diameters estimated from the equivalent circular areas and so on.

Once the apparent grain sizes have been estimated, we have several choices:

- Estimate different "average" values of apparent grain size and characterize the nature of the apparent grain size distribution

- Estimate differential stresses via paleopiezometers

- Approximate the actual 3D grain size distribution using stereological methods, including:

- The Saltykov method (Saltykov, 1967; Sahagian and Proussevitch, 1998)

- The two-step method (Lopez-Sanchez and Llana-Fúnez, 2016)

calc_grain_size is the function responsible for estimating different "average" grain size values (mean, median, and frequency peak) and explore the nature of the apparent grain size distribution. When calling, the calc_grain_size function returns several statistic parameters and different plots. The simplest way to interact with this function is to enter the variable that contains the equivalent circular diameters as follows:

>>> calc_grain_size(diameters)First of all, note that contrary to what was shown so far, the function is called directly in the console since it is no longer necessary to store any data into a variable. In the above example, the function will return by default a frequency vs apparent grain size plot using a linear scale along with the mean, RMS mean, median, and frequency peak apparent grain sizes among others; the latter using a Gaussian kernel density estimator (see details in Lopez-Sanchez and Llana-Fúnez 2015). The output in the console will look something like this (v2.0.3 or higher):

CENTRAL TENDENCY ESTIMATORS

Arithmetic mean = 34.79 microns

Geometric mean = 30.1 microns

RMS mean = 39.31 microns (discouraged)

Median = 31.53 microns

Peak grain size (based on KDE) = 24.11 microns

DISTRIBUTION FEATURES (SPREADING AND SHAPE)

Standard deviation = 18.32 (1-sigma)

Interquartile range (IQR) = 23.98

Multiplicative standard deviation (lognormal shape) = 1.75

HISTOGRAM AND KDE FEATURES

The modal interval is 16.83 - 20.24

The number of classes are 45

The bin size is 3.41 according to the auto rule

KDE bandwidth = 4.01 (silverman rule)

Maximum precision = 0.01

The plot, which will appear in a separate window, shows the distribution of apparent grain sizes and the location of the different "average" grain size measures respect to the population (Fig. 6). You can save it by clicking in the floppy disk icon. Another interesting option is to modify the appearance of the plot before saving by clicking on the figure options icon. This allows to modify or hide any element on the plot.

Figure 6. The window containing the plot.

The calc_grain_size function has up to six different inputs that we will commented on in turn:

def calc_grain_size(diameters,

areas=None,

plot='lin',

binsize='auto',

bandwidth='silverman',

precision=0.01):

""" ...

Parameters

----------

diameters : array_like

the apparent diameters of the grains

areas : array_like or None, optional

the areas of the grain profiles

plot : string, optional

the scale or type of plot

| Types:

| 'lin' frequency vs linear diameter distribution

| 'log' frequency vs logarithmic (base e) diameter distribution

| 'log10' frequency vs logarithmic (base 10) diameter distribution

| 'sqrt' frequency vs square root diameter distribution

| 'area' area-weighted frequency vs diameter distribution

| 'norm' normalized grain size distribution

binsize : string or positive scalar, optional

If 'auto', it defines the plug-in method to calculate the bin size.

When integer or float, it directly specifies the bin size.

Default: the 'auto' method.

| Available plug-in methods:

| 'auto' ('fd' if sample_size > 1000 or 'sturges' otherwise)

| 'doane' (Doane's rule)

| 'fd' (Freedman-Diaconis rule)

| 'rice' (Rice's rule)

| 'scott' (Scott rule)

| 'sqrt' (square-root rule)

| 'sturges' (Sturge's rule)

bandwidth : string {'silverman' or 'scott'} or positive scalar, optional

the method to estimate the bandwidth or a scalar directly defining the

bandwidth. It uses the Silverman plug-in method by default.

precision : positive scalar, optional

the maximum precision expected for the "peak" kde-based estimator.

Default is 0.01

...

"""The plot parameter allows you to define scales other than the linear one (which is the default scale), including the logarithmic (with base plot parameter also allows you other options such as estimate the area-weighted grain size population (Fig. 8) or normalized apparent grain size populations. The latter are key when we want to compare different apparent grain size distributions that have different "average" grain size values. This option will be discussed in more detail in a subsection later. Some examples using the different options of the plot parameter below:

>>> calc_grain_size(diameters, plot='log') # use a log scale with base e

>>> calc_grain_size(diameters, plot='log10') # use log scale with base 10

>>> calc_grain_size(diameters, plot='sqrt') # use a square-root scale

>>> calc_grain_size(diameters, plot='norm') # use a log-normalized scale

>>> calc_grain_size(diameters, areas=areas, plot='area') # note that we include the areas here!

Figure 7. Same grain size dataset showing different grain size scales. These include linear (upper), logarithmic with base e (lower left), and square root (lower right) scales.

Figure 8. Area-weighted apparent grain size distribution and the location of the area-weighted mean.

The function allows us to use different plug-in methods implemented in the Numpy package to estimate "optimal" bin sizes for the construction of histograms. For this, we use the parameter binsize. The default mode, called 'auto', uses the Freedman-Diaconis rule when using large datasets (> 1000) and the Sturges rule otherwise. Other available rules are the Freedman-Diaconis 'fd', Scott 'scott', Rice 'rice', Sturges 'sturges', Doane 'doane', and square-root 'sqrt'. For more details on these methods see here. We encourage you to use the default method 'auto'. Empirical experience indicates that the 'doane' and 'scott' methods work also pretty well when you have lognormal- and normal-like distributions, respectively. Some examples specifying different plug-in methods below:

>>> calc_grain_size(diameters, plot='lin', binsize='doane')

>>> calc_grain_size(diameters, plot='log', binsize='scott')The parameter binsize also allows you to define a specific bin size if you declare a positive scalar instead (integer or floating/irrational) as shown below:

>>> calc_grain_size(diameters, plot='lin', binsize=7.5)Lastly, the parameter bandwidth allows you to define a method to estimate an optimal bandwidth to construct the KDE, either the 'silverman' (the default) or the scott rules. You can also define your own bandwidth value by declaring a positive scalar instead. The 'silverman' and the 'scott' rules, are both optimized for normal-like distributions, so they perform better when using logarithmic or square-root scales. However, sometimes these rules-of-thumb fail and the estimated KDE show undersmoothing issues in some places. For example, in figure 7 it seems that when using the square root scales the KDE estimator produces a small valley near the maximum values, which likely indicates a local undersmoothing problem. To smooth a bit the KDE we can increase the bandwidth from 0.33, which is the bandwidth estimated by the Silverman rule, to for example 0.5 as follows (Fig. 9):

calc_grain_size(diameters, plot='sqrt', bandwidth=0.5)Figure 9. Apparent grain size distribution in a square root scale but with a KDE bandwidth manually set to 0.5.

Note that in comparison to the same representation in Figure 7, the approximation of the grain size distribution using the KDE in figure 9 is smoother and yields a better estimate of the frequency peak in this particular case (i.e. in line with the values of the median and the mean).

As mentioned above, the parameter plot allows you to estimate and visualize normalized grain size distributions (Fig. 10). This is means that the entire grain population is normalized using the mean, the median, or the frequency peak; in this case it uses a logarithmic scale with base e. The advantage of normalized distributions is that they allow us to compare whether the grain size distribution looks similar or not even when the average grain size between different distributions is different. For example, to test whether two or more apparent grain size distributions have similar shapes we can compare their normalized standard deviations (SD) or interquartile ranges (IQR). For this, we set the parameter plot='norm' and then the script will ask you about what average measure you want to use to normalize the grain size population:

>>> calc_grain_size(diameters, plot='norm')

Define the normalization factor (1 to 3)

1 > mean; 2 > median; 3 > max_freq: 1 # we write 1 to use the mean in this example and then press Enter

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS

Arithmetic mean grain size = 1.0 microns # Note that the mean is then equal to 1

Standard deviation = 0.16 (1-sigma)

(...)Keep in mind that if you want to use the SD for comparative purposes you should normalize the grain size distribution using the arithmetic mean (option 1). In contrast, if you prefer the IQR you should normalize the grain size distribution using the median (option 2). The normalization of the grain size population using the frequency peak (option 3) is useful to compare the asymmetry of different populations by measuring the difference between the frequency peak and the mean or mode.

Figure 10. Apparent grain size distribution normalized to median = 1 in logarithmic scale.

The script includes a function for estimating differential stress via paleopiezomers based on "average" apparent grain sizes called calc_diffstress . This includes common mineral phases such as quartz, calcite, olivine and albite. The function requires measuring the grain size as equivalent circular diameters and entering the apparent grain sizes in microns although the type of "average" grain size to be entered depends on the piezometric relation. We provide a list of the all piezometric relations available, the average grain size value to use, and the different experimentally-derived parameters in Tables 1 to 5. In addition, you can get a list of the available piezometric relations in the console just by calling quartz(), calcite(), olivine, or feldspar(). An example below:

>>> quartz()

Available piezometers:

'Cross'

'Cross_hr'

'Holyoke'

'Holyoke_BLG'

'Shimizu'

'Stipp_Tullis'

'Stipp_Tullis_BLG'

'Twiss'The calc_diffstress requires entering three different inputs: (1) the apparent grain size, (2) the mineral phase, and (3) the piezometric relation. We provide some examples below:

>>> calc_diffstress(grain_size=5.7, phase='quartz', piezometer='Stipp_Tullis')

differential stress = 169.16 MPa

Ensure that you entered the apparent grain size as the root mean square (RMS)!

>>> calc_diffstress(grain_size=35, phase='olivine', piezometer='VanderWal_wet')

differential stress = 282.03 MPa

Ensure that you entered the apparent grain size as the mean in linear scale!

>>> calc_diffstress(grain_size=35, phase='calcite', piezometer='Rutter_SGR')

differential stress = 35.58 MPa

Ensure that you entered the apparent grain size as the mean in linear scale!It is key to note that different piezometers require entering different apparent grain size averages to provide meaningful estimates. For example, the piezometer relation of Stipp and Tullis (2003) requires entering the grain size as the root mean square (RMS) using equivalent circular diameters with no stereological correction, and so on. Table 1 show all the implemented piezometers in GrainSizeTools v2.0+ and the apparent grain size required for each one. Despite some piezometers were originally calibrated using linear intercepts (LI), the script will always require entering a specific "average" grain size value measured as equivalent circular diameters (ECD). The script will automatically convert this ECD value to linear intercepts using the De Hoff and Rhines (1968) empirical relation. Also, the script takes into account if the authors originally used a specific correction factor for the grain size. For more details on the piezometers and the assumption made use the command help() in the console as follows:

>>> help(calc_diffstress)Table 1. Relation of piezometers (in alphabetical order) and the apparent grain size required to obtain meaningful differential stress estimates

| Piezometer | Apparent grain size† | DRX mechanism | Phase | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Barnhoorn |

Mean | SRG, GBM | calcite | Barnhoorn et al. (2004) |

Cross and Cross_hr |

RMS mean | BLG, SGR | quartz | Cross et al. (2017) |

'Holyoke' |

RMS mean | Regimes 2, 3 | quartz | Holyoke and Kronenberg (2010) |

'Holyoke_BLG' |

RMS mean | Regime 1 (BLG) | quartz | Holyoke and Kronenberg (2010) |

'Jung_Karato'§ |

Mean | BLG | olivine, wet | Jung & Karato (2001) |

'Platt_Bresser' |

RMS mean | BLG, SGR | calcite | Platt and De Bresser (2017) |

'Post_Tullis_BLG'§ |

Median | BLG | albite | Post and Tullis (1999) |

'Rutter_SGR' |

Mean | SGR | calcite | Rutter (1995) |

'Rutter_GBM' |

Mean | GBM | calcite | Rutter (1995) |

'Schmid'§ |

SGR | calcite | Schmid et al. (1980) | |

'Shimizu'‡ |

Median in log(e) scale | SGR + GBM | quartz | Shimizu (2008) |

'Stipp_Tullis' |

RMS mean | Regimes 2, 3 | quartz | Stipp & Tullis (2003) |

'Stipp_Tullis_BLG' |

RMS mean | Regime 1 (BLG) | quartz | Stipp & Tullis (2003) |

'Twiss'§ |

Mean | Regimes 2, 3 | quartz | Twiss (1977) |

'Valcke' |

Mean | BLG, SGR | calcite | Valcke et al. (2015) |

'VanderWal_wet'§ |

Mean | Olivine, wet | Van der Wal et al. (1993) |

† Apparent grain size measured as equivalent circular diameters (ECD) with no stereological correction and reported in microns. The use of non-linear scales are indicated

‡ Shimizu piezometer requires to provide the temperature during deformation in K

§ These piezometers were originally calibrated using linear intercepts (LI) instead of ECD

Table 2. Parameters relating the average apparent size of dynamically recrystallized grains and differential stress in quartz using a relation in the form d = Aσ-p or σ = Bd-m

| Reference | phase | DRX | A†,‡ | p† | B†,‡ | m† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross et al. (2017)§ | quartz | Regimes 2, 3 | 8128.3 | 1.41 | 593.0 | 0.71 |

| Cross et al. (2017)§ | quartz hr | Regimes 2, 3 | 16595.9 | 1.59 | 450.9 | 0.63 |

| Holyoke & Kronenberg (2010)¶ | quartz | Regimes 2, 3 | 2451 | 1.26 | 490.3 | 0.79 |

| Holyoke & Kronenberg (2010)¶ | quartz | Regime 1 | 39 | 0.54 | 883.9 | 1.85 |

| Shimizu (2008) | quartz | SGR + GBM | 1525 | 1.25 | 352 | 0.8 |

| Stipp and Tullis (2003) | quartz | Regimes 2, 3 | 3630.8 | 1.26 | 669.0 | 0.79 |

| Stipp and Tullis (2003) | quartz | Regime 1 | 78 | 0.61 | 1264.1 | 1.64 |

| Twiss (1977) | quartz | Regimes 2, 3 | 1230 | 1.47 | 550 | 0.68 |

† B and m relate to A and p as follows: B = A1/p and m = 1/p

‡ A and B are in [μm MPap, m]

§ Cross et al. (2017) reanalysed the samples of Stipp and Tullis (2003) using EBSD data for reconstructing the grains. Specifically, they use grain maps with a 1 m and a 200 nm (hr - high-resolution) step sizes . This is the preferred piezometer for quartz when grain size data comes from EBSD maps

¶ Holyoke and Kronenberg (2010) provides a recalibration of the Stipp and Tullis (2003) piezometer

Table 3. Parameters relating the average apparent size of dynamically recrystallized grains and differential stress in olivine

| Reference | phase | DRX | A†,‡ | p† | B†,‡ | m† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jung and Karato (2001) | olivine, wet | BLG | 25704 | 1.18 | 5461.03 | 0.85 |

| Van der Wal et al. (1993) | olivine, dry/wet | 14800 | 1.33 | 1355.4 | 0.75 |

Table 4. Parameters relating the average apparent size of dynamically recrystallized grains and differential stress in calcite

| Reference | phase | DRX | A†,‡ | p† | B†,‡ | m† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barnhoorn et al. (2004) | calcite | SRG, GBM | 2134.4 | 1.22 | 537.03 | 0.82 |

| Platt and De Bresser (2017) | calcite | BLG, SGR | 2141 | 1.22 | 538.40 | 0.82 |

| Rutter (1995) | calcite | SGR | 2026.8 | 1.14 | 812.83 | 0.88 |

| Rutter (1995) | calcite | GBM | 7143.8 | 1.12 | 2691.53 | 0.89 |

| Valcke et al. (2015) | calcite | BLG, SGR | 79.43 | 0.6 | 1467.92 | 1.67 |

Table 5. Parameters relating the average apparent size of dynamically recrystallized grains and differential stress in albite

| Reference | phase | DRX | A†,‡ | p† | B†,‡ | m† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post and Tullis (1999) | albite | BLG | 55 | 0.66 | 433.4 | 1.52 |

Since v2.0.1, the calc_diffstress function allows correcting the differential stress estimates for plane stress using the correction factor proposed by Paterson and Olgaard (2000). The rationale behind this is that experiments designed to calibrate paleopiezometers are performed in uniaxial compression while shear zones approximately behave as plane stress volumes. To correct this Paterson and Olgaard (2000) (see also Behr and Platt, 2013) proposed to multiply the estimates by 2 / √3. To do this we specify:

# Note that we set the parameter 'correction' to True

>>> calc_diffstress(grain_size=5.7, phase='quartz', piezometer='Stipp_Tullis', correction=True)

differential stress = 195.32 MPa

Ensure that you entered the apparent grain size as the root mean square (RMS)!As pointed out in the scope section, when using paleopiezometers the optimal approach is to obtain several estimates of stress and then estimate a confidence interval. The same principle may apply to apparent grain size estimates. The script implements a function called confidende_intervalfor estimating a robust confidence interval that takes into account the sample size. For this, it uses the student's t-distribution with n-1 degrees of freedom. The function has two inputs, the dataset with the estimates, which is obligatory, and the level of the confidence interval, which is optional and set at 0.95 by default. For example:

>>> my_results = [165.3, 174.2, 180.1] # this is just a list with three different estimates (note they are separated by commas)

>>> confidence_interval(data=my_results, confidence=0.95)The function will return the following information in the console:

Confidence set at 95.0 %

Mean = 173.2 ± 18.51

Max / min = 191.71 / 154.69

Coefficient of variation = 10.7 %

👉 The coefficient of variation express the confidence interval in percentage respect to the mean and allows the user to compare errors between samples with different mean values.

Approximate the actual 3D grain size distribution and estimate the volume of a specific grain size fraction using the Saltykov method

The function responsible to unfold the distribution of apparent 2D grain sizes into the actual 3D grain size distribution is named Saltykov. The method is based on the Scheil-Schwartz-Saltykov method (Saltykov, 1967) using the generalization proposed by Sahagian and Proussevitch (1998) with some variations explained in Lopez-Sanchez and Llana-Fúnez (2016). This method is the best option for estimating the volume of a particular grain size fraction. The Saltykov functions has the following inputs:

def Saltykov(diameters,

numbins=10,

calc_vol=None,

text_file=None,

return_data=False,

left_edge=0):

"""...

Parameters

----------

diameters : array_like

the apparent diameters of the grains

numbins : positive integer, optional

the number of bins/classes of the histrogram. If not declared, is set

to 10 by default

calc_vol : positive scalar or None, optional

if the user specifies a number, the function will return the volume

occupied by the grain fraction up to that value.

text_file : string or None, optional

if the user specifies a name, the function will return a csv file

with that name containing the data used to construct the Saltykov

plot

return_data : bool, optional

if True the function will return the position of the midpoints and

the frequencies (use by other functions).

left_edge : positive scalar or 'min', optional

set the left edge of the histogram.

...Some examples of the their use below:

# Apply the Saltykov method using twelve number of classes (if numbins is not declared the number of classes is set to ten)

>>> Saltykov(diameters, numbins=12)

# Use 15 classes and save the estimation in a csv file named 'saltykov_data.csv' (you can use any file name)

>>> Saltykov(diameters, numbins=15, text_file='saltykov_data.csv')

# Use 15 classes and estimate the volume occupied by all the particles less than or equal to 40 microns

>>> Saltykov(diameters, numbins=15, calc_vol=40)

# Use 12 classes and set the minimum value of the histogram according to the minimum value measured (it is set to zero by default)

>>> Saltykov(diameters, numbins=12, left_edge='min')

# The output on the console will look approximately like this

volume fraction (up to 40 microns) = 20.97 %

bin size = 13.05

The file saltykov_data.csv was createdSince the Saltykov method uses the histogram to derive the actual 3D grain size distribution, the inputs are an array containing the population of apparent diameters of the grains and the number of classes. As shown in the example above, if the number of classes is not declared is set to ten by default. The user can use any positive integer to define the number of classes. However, it is usually advisable to choose a number not exceeding 20 classes (see later for details).

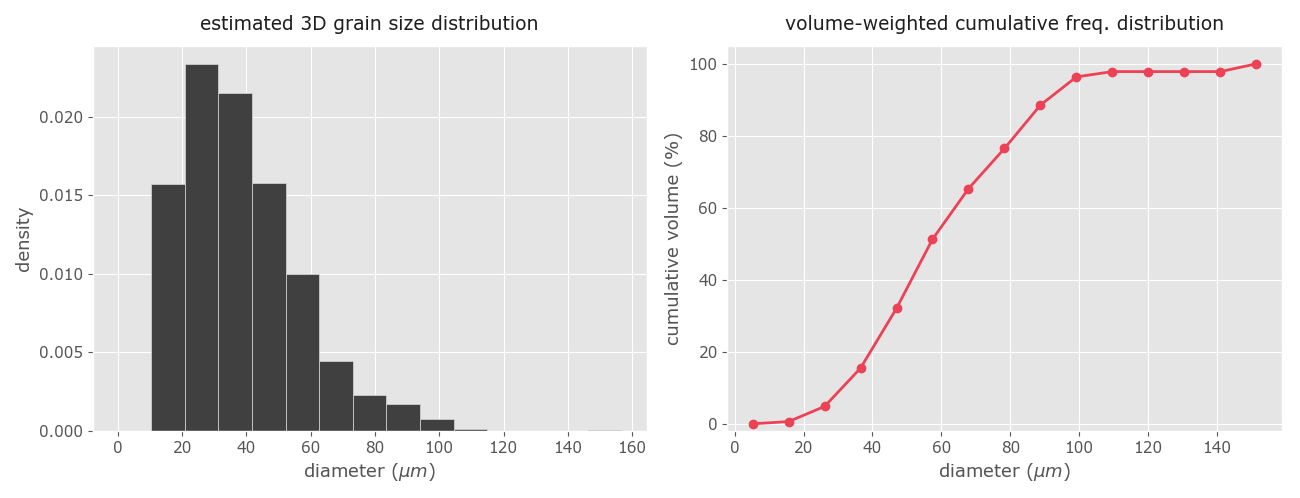

This function also generates two plots (Fig 11). On the left it is the frequency plot with the estimated 3D grain size distribution in the form of a histogram. On the right the corresponding volume-weighted cumulative density curve. The latter allows the user to estimate qualitatively the percentage of volume occupied by a defined fraction of grain sizes. If the user wants to estimate quantitatively the volume of a particular grain fraction (i.e. the volume occupied by a fraction of grains less or equal to a certain value) specify the calc_vol input as in the last example above.

As a cautionary note, if we use a different number of bins/classes, in this example above set at 12, you will obtain slightly different volume estimates. This is normal due to the inaccuracies of the Saltykov method. In any event, Lopez-Sanchez and Llana-Fúnez (2016) proved that the absolute differences between the volume estimations using a range of classes between 10 and 20 are below ±5. This means that to stay safe we should always take an absolute error margin of ±5 in the volume estimations.

Figure 11. The derived 3D grain size distribution and the volume-weighted cumulative grain size distribution using the Saltykov method.

👉 Due to the nature of the Saltykov method, the smaller the number of classes the better the numerical stability, and the larger the number of classes the better the approximation of the wanted distribution. Ultimately, the strategy to follow is about finding the maximum number of classes (i.e. the best resolution) that produces stable results. Based on experience, some authors have been proposed to use between 10 to 15 classes (e.g. Exner 1972), although depending on the quality and the size of the dataset it seems that it can be used safely up to 20 classes (e.g. Heilbronner and Barret 2014, Lopez-Sanchez and Llana-Fúnez 2016). Yet, no method (i.e. algorithm) appears to be generally best for choosing an optimal number of classes (or bin size) for the Saltykov method. Hence, the only way to find the maximum number of classes with consistent results is to use a trial and error strategy and observe if the appearance is coherent or not. As a last cautionary note, the Saltykov method requires large datasets (n ~ 1000 or larger) to obtain consistent (i.e. meaningful) results, even when using a small number of classes.

The two-step method is suitable to describe quantitatively the shape of the grain size distribution assuming that they follow a lognormal distribution. This means that the two-step method only yield consistent results when the population of grains considered are completely recrystallized or when the non-recrystallized grains can be previously discarded. It is therefore necessary to check first whether the linear distribution of grain sizes is unimodal and lognormal-like (i.e. skewed to the right as in the example shown in figure 11). For more details see Lopez-Sanchez and Llana-Fúnez (2016).

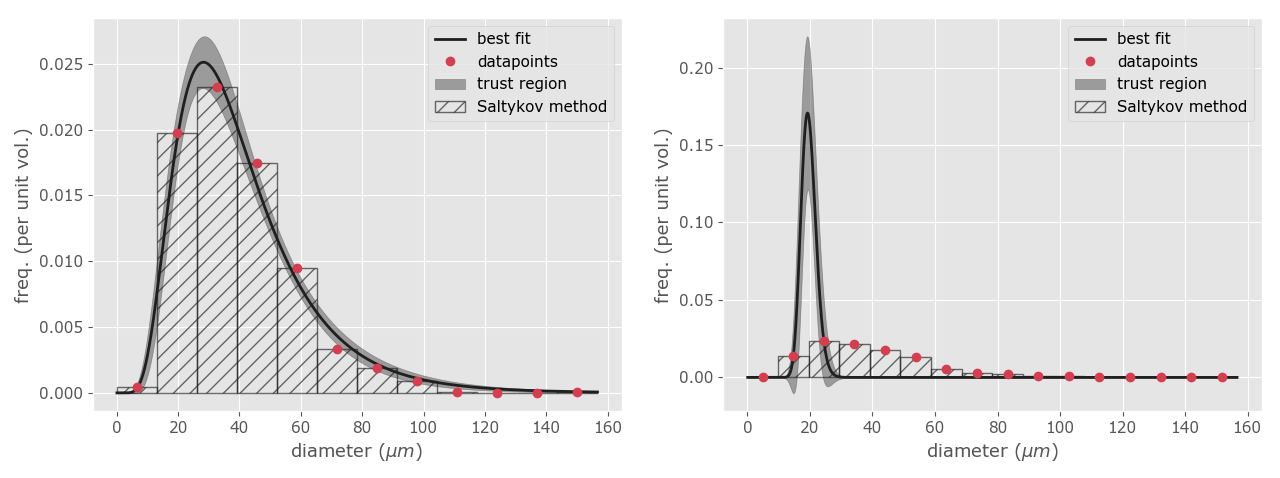

To estimate the shape of the 3D grain size distribution we will use the function calc_shape. This function implements a method called "the two-step method" (Lopez-Sanchez and Llana-Fúnez, 2016). Briefly, the method applies a non-linear least squares algorithm to fit a lognormal distribution on top of the Saltykov method using the midpoints of the different classes. The method return two parameters to fully describe a lognormal distribution at their original (linear) scale: the MSD and the geometric mean (which theoretically it coincides with the median in perfect lognormal distributions) along with the uncertainty associated with the estimate. In addition, it also returns a frequency plot showing the probability density function estimated (Fig. 12). In particular, the MSD value allows to describe the shape of the lognormal distribution independently of the scale (i.e. the range) of the grain size distribution, which is very convenient for comparative purposes. This is whether two distribution show the same shape distribution of grain sizes even when they have different grain size ranges and average grain sizes. The calc_shape functions has the following inputs:

def calc_shape(diameters, class_range=(12, 20), initial_guess=False):

""" ...

Parameters

----------

diameters : array_like

the apparent diameters of the grains

class_range : tupe or list with two values, optional

the range of classes considered. The algorithm will estimate the optimal

number of classes within this range.

initial_guess : boolean, optional

If False, the script will use the default guessing values to fit a

lognormal distribution. If True, the script will ask the user to define

their own MSD and median guessing values.

"""This method assumes that the actual 3D population of grain sizes follows a lognormal distribution, a common distribution observed in recrystallized aggregates. Hence, make sure that the aggregate or the studied area within the rock/alloy/ceramic is completely recrystallized. To apply the two-step method we need to invoke the function derive3D as follows:

>>> calc_shape(diameters)Note that in this case we include a new parameter named fit that it is set to True with the "T" capitalized (it is set to False by default). The function will return something like this in the shell:

OPTIMAL VALUES

Number of clasess: 11

MSD (shape) = 1.63 ± 0.06

Geometric mean (location) = 36.05 ± 1.27

By default, the algorithm find the optimal number of classes within the range 10 to 20. However, sometimes it will be necessary to define a different range. For example when we observe very thick trust regions, which is indicative that we may be using a minimum number of classes too large for the dataset. We can define any other range as follows:

>>> calc_shape(diameters, class_range=(15, 20))

OPTIMAL VALUES

Number of clasess: 15

MSD (shape) = 1.69 ± 0.07

Geometric mean (location) = 35.51 ± 1.73

Figure 12. Lognormal approximation using the two-step method. At left, an example with the lognormal pdf well fitted to the data points. The shadow zone is the trust region for the fitting procedure. At right, an example with a wrong fit due to the use of unsuitable initial guess values. Note the discrepancy between the data points and the line representing the best fitting.

Sometimes, the least squares algorithm will fail at fitting the lognormal distribution to the unfolded data (e.g. Fig. 12b). This is due to the algorithm used to find the optimal MSD and median values, the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm (Marquardt, 1963), only converges to a global minimum when their initial guesses are already somewhat close to the final solution. Based on our experience in quartz aggregates, the initial guesses were set by default at 1.2 and 35.0 for the MSD and geometric mean values respectively. However, if the algorithm fails it is possible to change the default values by adding a following parameter:

>>> calc_shape(diameters, initial_guess=True)

Initial guess for the MSD parameter (the default is 1.2; common values 1.2-1.8): 1.6

Initial guess for the expected geometric mean (the default is 35.0): 40.0When the initial_guess parameter is set to True, the script will ask you to set new starting values for both parameters (it also indicates which were the default ones). Based in our experience, a useful strategy is to let the MSD value in its default value (1.2) and increase or decrease the geometric mean value every five units until the fitting procedure yield a good fit (Fig. 12). You can also try using a value similar to the median or the geometric mean of the apparent grain size population.

Quantile-quantile plots are a useful visualization to test whether the dataset do or do not follow a given distribution. In this case, the GrainSizeTools script (v2.0.3 or higher) contains a function to test whether the dataset do or do not follow a lognormal distribution. For this:

>>> test_lognorm(diameters)Figure. q-q plot of the test dataset

If the points fall right onto the reference line, then the grain size values are lognormally or approximately lognormally distributed. In such case, the dataset is appropriate for using the two-step method or characterize the population of apparent diameters using the multiplicative (geometric) standard deviation. To know more about this type of plots see https://serialmentor.com/dataviz/

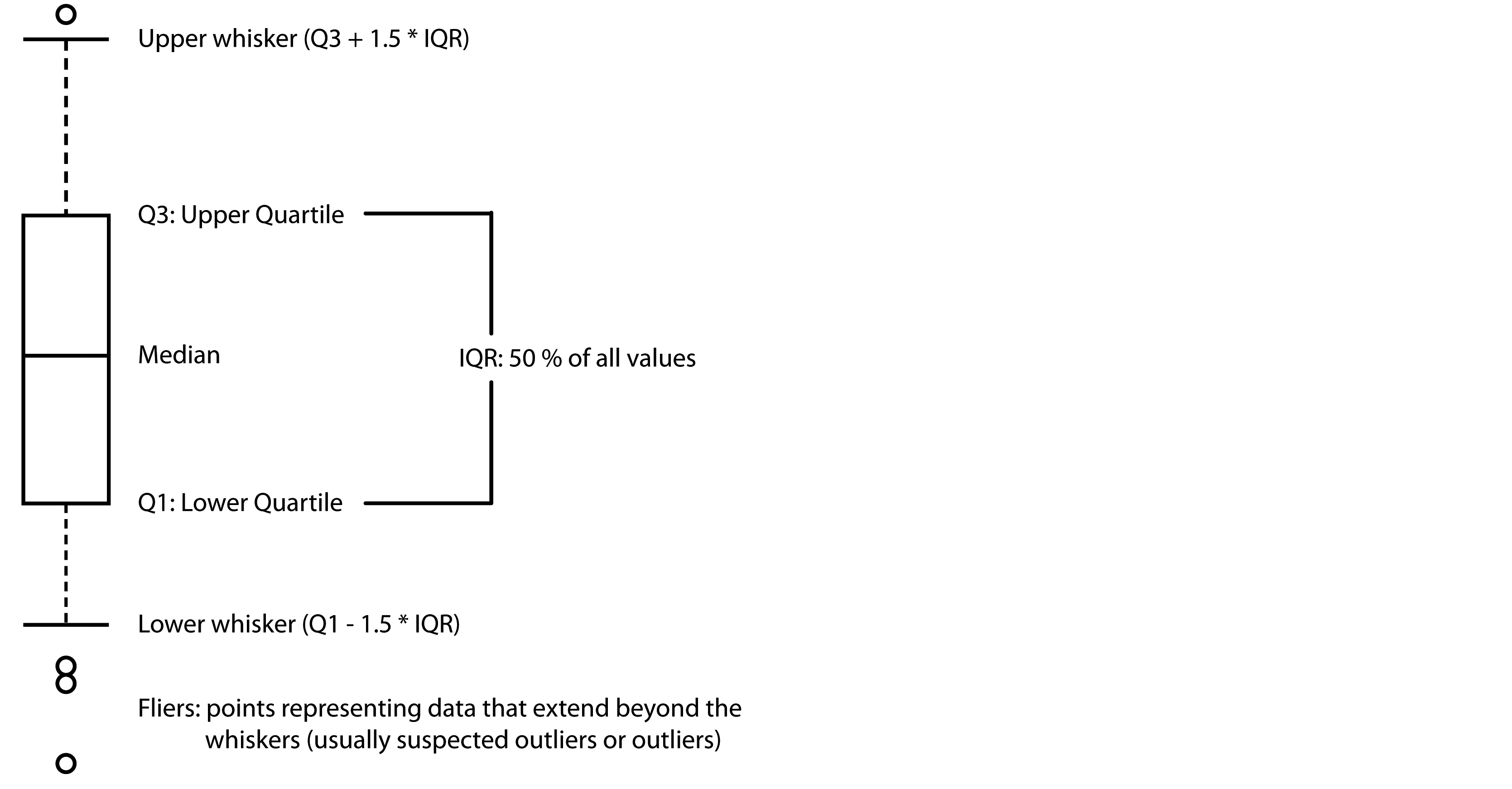

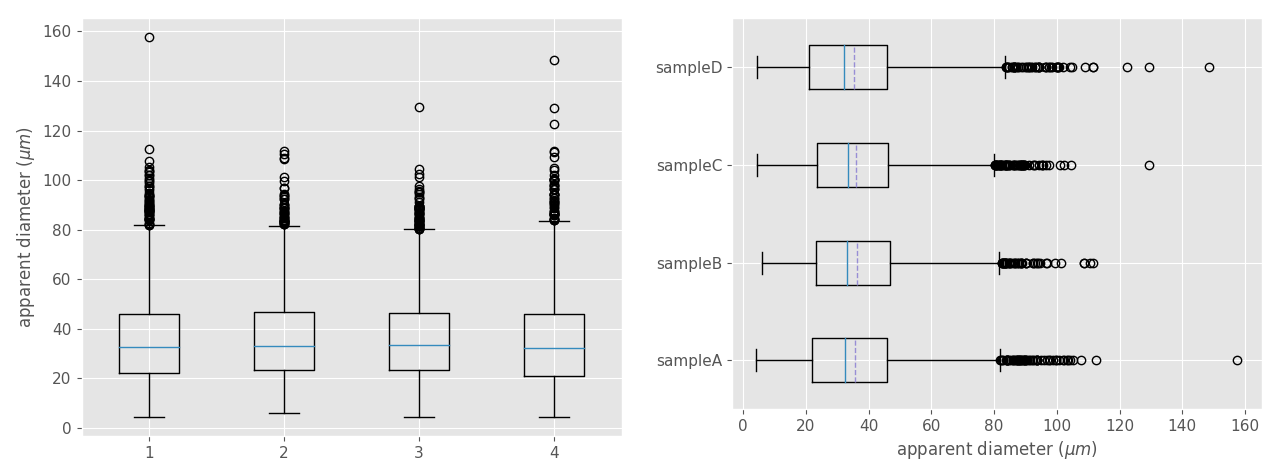

Box (or box-and-whisker) plot is a non-parametric method to display numerical datasets through their quartiles and median, being a very efficient way for comparing unimodal datasets graphically. Figure 13 show the different elements represented in a typical box plot.

To create a box plot using the Matplotlib library we need to create first a variable with all the data sets to represent. For this we create a Python list as follows (variable names have been chosen for convenience):

>>> all_data = [dataset1, dataset2, dataset3, dataset4] # Note that a Python list is a list of elements within brackets separated by commas

# if you prefer logarithmic scales then: all_data = [log(dataset1), ...]Then we create the plot (Fig. 14):

>>> plt.boxplot(all_data)

>>> plt.show() # write this and click return if the plot did not appear automatically (generally not needed)To create a better-looking plot (Fig. 14b) we propose using the following optional parameters:

# First make a list specifying the labels of the samples (this is optional). Ensure that the number of items in the brackets coincide with the number of datasets to plot.

>>> label_list = ['SampleA', 'SampleB', 'SampleC', 'SampleD']

# Then make the plot ading the following instructions

>>> plt.boxplot(all_data, vert=False, meanline=True, showmeans=True, labels=label_list)

>>> plt.xlabel('apparent diameter ($\mu m$)') # add the x-axis label

>>> plt.show() # write this and click return if the plot did not appear automaticallyThe parameters defined in the boxplot are:

vert: if False makes the boxes horizontal instead of vertical (it is True by default).meanlineandshowmeans: if True will show the location of the mean within the plots.labels: add labels to the different datasets.

Figure 14. Box plot comparing four unimodal datasets obtained from the same sample but located in different places along the thin section. At left, a box plot with the default appearance. At right, the same box plot with the optional parameters showing above. Dashed lines are the mean. Note that the all the datasets show similar median, means, IQRs, and whisker locations. In contrast, the fliers (points) approximately above 100 microns vary greatly.

Figure 14. Box plot comparing four unimodal datasets obtained from the same sample but located in different places along the thin section. At left, a box plot with the default appearance. At right, the same box plot with the optional parameters showing above. Dashed lines are the mean. Note that the all the datasets show similar median, means, IQRs, and whisker locations. In contrast, the fliers (points) approximately above 100 microns vary greatly.

To merge two or more datasets we can use the Numpy method concatenate, which stack arrays in sequence as follows (please, note the use of brackets between parentheses):

np.concatenate([name of the array1, name of the Array2,...])As an example if we want to merge two different datasets into a new variable (variable names are just random examples):

>>> all_ECD = np.concatenate([diameters1, diameters2])Note that in the example above we do not overwrite any of the original variables and we can used them later if required. In contrast, if you use a variable name already defined as in the example below:

>>> diameters1 = np.concatenate([diameters1, diameters2])the original diameters1 variable no longer exists since these variables -strictly speaking Numpy arrays- are mutable Python objects.

You can interact and use the script using Jupyter notebooks, a tool that allows you to create and share documents that contain live code, equations, visualizations and narrative text. For this, you will need to enter the following two lines of code at the beginning of the notebook

%matplotlib inline

%run ...full filepath.../grain_size_tools/GrainSizeTools_script.pyThe first one allows you to visualize the plots inline and the second one run the script, ensure that you specify the whole path. You can find an specific example on how to interact between the script and the Jupyter Notebooks here

next section

table of contents