A data pipeline to show calculated historical weather at U.S. campsites based on the nearest weather stations, using the 260 GB NOAA weather dataset, built during my time as a Data Engineering Fellow at Insight Data Science.

The purpose is to build a data pipeline that will support a web application that will show both historic and realtime weather conditions at campsites.

The end product is a web application that allows a user to find the historical weather at a campsite for a specific day by choosing a campsite on a map. The core project was to build out a data pipeline that would perform the data transformations needed to get the above functionality, store the data to a database, and to serve the web app.

Through my time working on this project, I discovered a bottleneck in the spark-cassandra-connector, which I alleviated in an unexpected way. This turned out to be the most interesting discovery I made during the course of the project. DataStax currently has an open JIRA issue, addressing ways to automatically alleviate this bottleneck.

S3. HDFS is more performant than S3 for computations. However, S3 is a lot cheaper than HDFS, and since it is a managed service, getting the file store up and running will be a lot quicker. These are important considerations for a project that will be utilizing Insight's resources, as well as a project that requires a very quick turnaround time. I chose to go with S3.

Spark. Both Spark and Flink have batch processing frameworks, but are built with different mindsets. Spark is primarily a batch-oriented framework, and views streaming as a batch process over a small period of time (e.g. 1 s). Flink is focused on truly real-time processing, and views batch processing as a special case of stream processing (bounded stream processing). Flink has lower latency than Spark, but for this application, achieving a small decrease in latency for the computations will not affect our results much, and the results are not mission critical. Additionally, using one common tool helps to reduce the complexity of the codebase - the batch and streaming portions of the pipeline can reuse much of the same code.

Cassandra. The raw data from NOAA dates back two decades, and the end goal is to store hourly data, for both weather stations, and for campsites. This means that the data is time-series in nature. Cassandra's column-oriented architecture is a good fit for time-series data.

The NOAA weather dataset is a dataset that contains a weather summary for every day dating back two decades (260 GB). It contains weather conditions at every individual weather station for different times throughout the past two decades. There is also a list of all campsites in the U.S. (~4000). Campsites are at different locations than weather stations, so in order to calculate the weather at a campsite, a weighted average from nearby weather stations needs to be calculated. The weight is a function of distance - closer weather stations should have a stronger effect on the calculation of the weather.

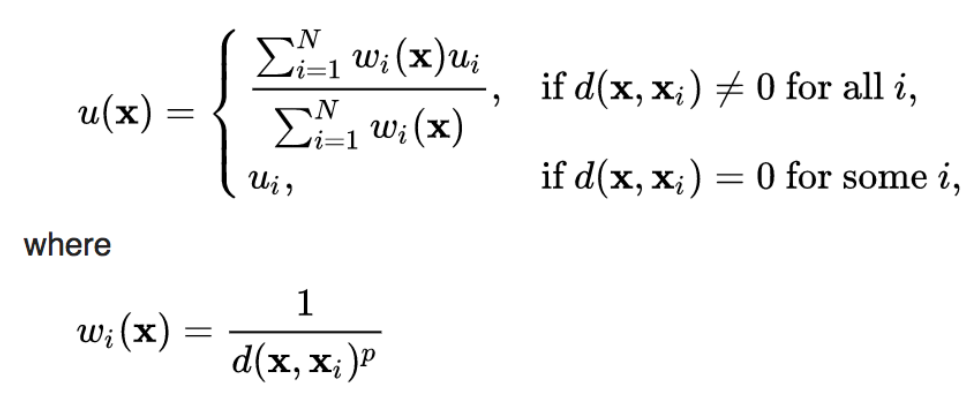

In order to calculate the hourly weather at campsites, a two-part algorithm was employed. First, a time-weighted average was calculated to obtain hourly temperature at weather stations. Then, a distance-weighted average was calculated to obtain hourly temperature at campsites, based on nearby weather stations. Here is the formula:

Here, weights are the inverse of time, or the inverse of distance. The p exponent can be used to scale how strongly the weighted average correlates with nearby (by time or distance) values.

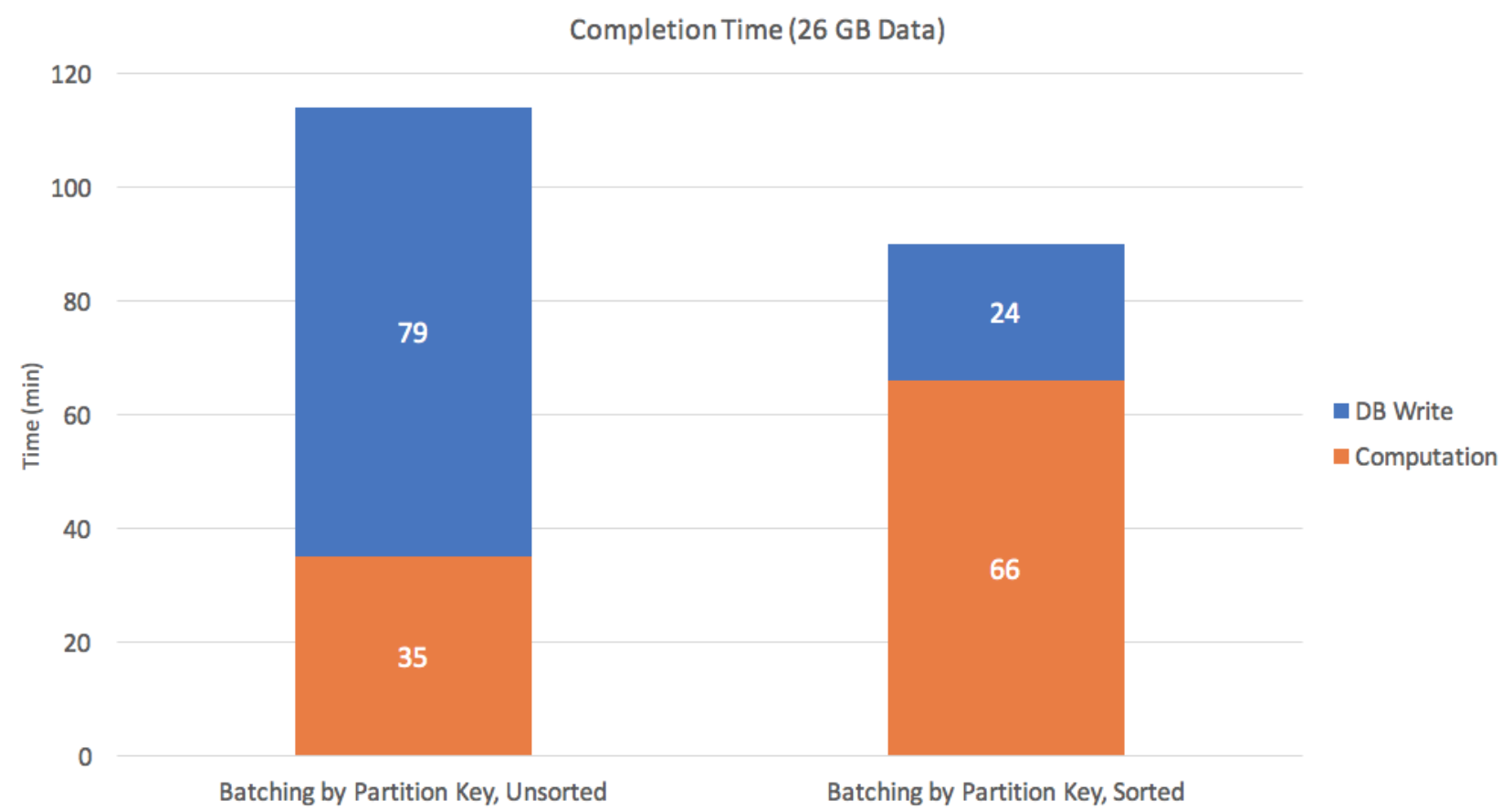

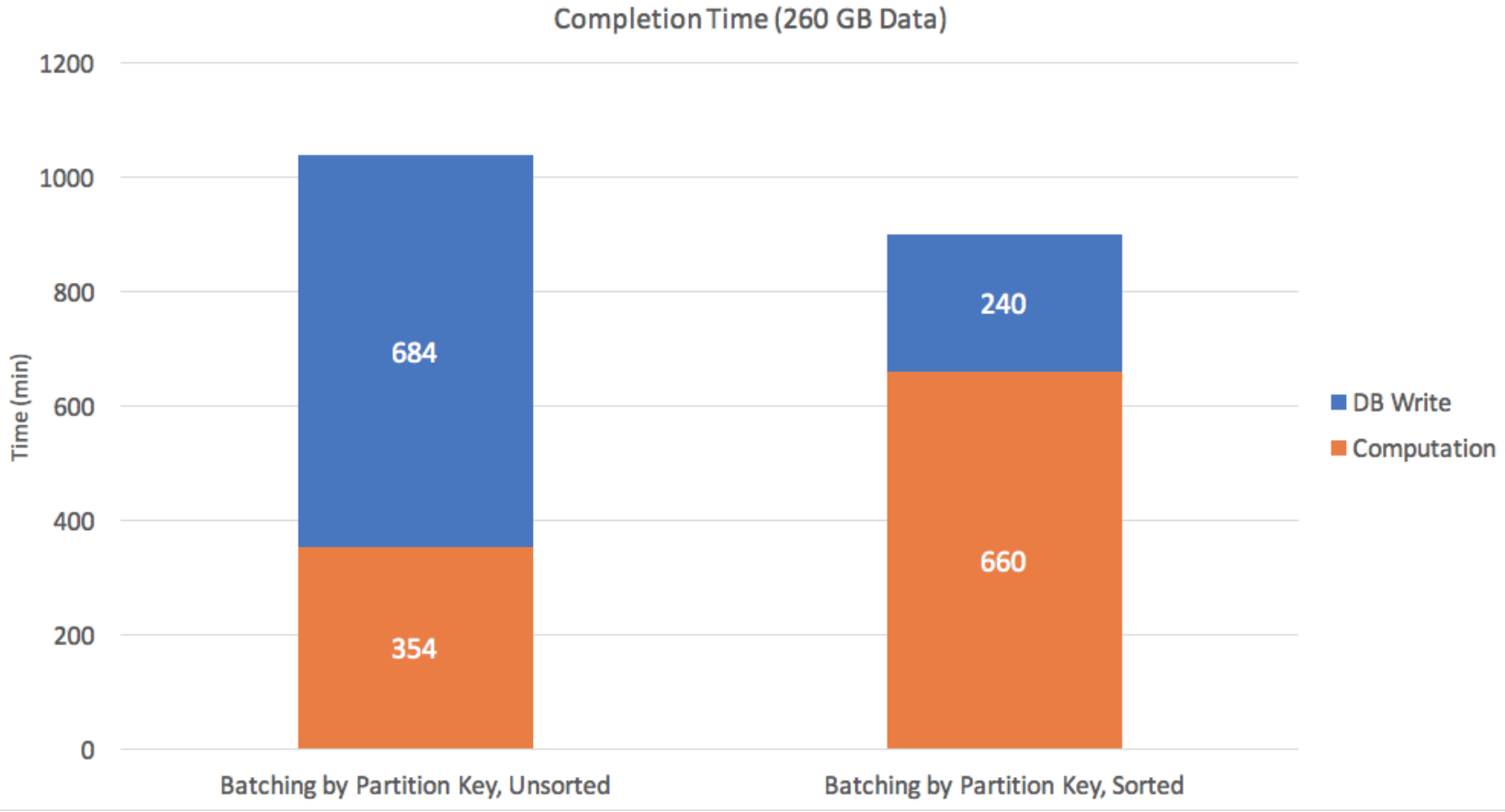

When I ran a 26 GB subset of my data through the pipeline, the completion time was about 2 hours. 35 minutes of this was due to computation time, and 79 minutes was due to writing to database. This is quite slow, so I dug into why.

The spark-cassandra-connector batches multiple rows for writing to database. There are several batching techniques, but it typically batches by partition key. In Cassandra, every row has a partition key, which determines which partition that row resides in on the Cassandra cluster.

It turns out that by sorting the data on Cassandra partition key prior to insertion to database, we can increase our write speed by 3x. Even though sorting results in extra computation time, the increase in write speed far outweighs the extra computation time. I found the same results when scaling up to a 260 GB dataset.

Since this is quite non-intuitive, there is interest in making modifications to the spark-cassandra-cluster to automatically sort on partition key prior to saving to database, in certain situations. Spark Catalyst, the pre-optimizer for Spark that speeds up DataFrame operations, can be extended to implement this functionality.

batch - PySpark code for performing calculations and saving to database

db_setup - CQL commands to set up namespaces and tables in Cassandra

img - Images for this README

nodeapp - Code for web app

raw_file_scripts - Assorted scripts for processing raw data