{:.no_toc}

- TOC {:toc}

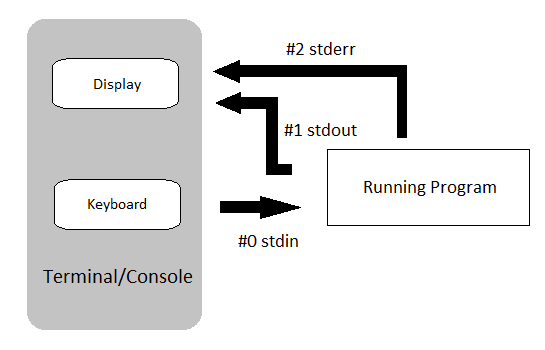

All of the output we saw in the previous practical was 'printed' to your terminal.

Each function returned output to you using a data stream called standard out, or stdout for short.

Most of these tools also send information to another data stream called standard error (or stderr), and this is where many error messages go.

This is actually sent to your terminal as well, and you may have seen this if you've made any mistakes so far.

This basic data flow can be visualised in the following chart from www.linuxunit.com.

Note also that everything you've typed on your keyboard is sent to each command as a data stream called stdin.

Any guesses what that is short for?

We can display a line of text in stdout by using the command echo.

The most simple function that people learn to write in most languages is called Hello World and we'll do the same thing today.

echo 'Hello World'

That's pretty amazing isn't it and you can make the terminal window say anything you want without meaning it.

echo 'This computer will self destruct in 10 seconds!'

There are a few subtleties about text which are worth noting.

If you have man pages accessible, inspect the man echo page and note the effects of the -e option. (Unfortunately you can't access this using echo --help.)

The -e option allows you to specify tabs (\t), new lines (\n) and other special characters by using the backslash to signify these characters.

This is an important concept and the use of a backslash to escape the normal meaning of a character is very common.

Try the following three commands and see what effects these special characters have.

echo 'Hello\tWorld'

echo -e 'Hello\tWorld'

echo -e 'Hello\nWorld'

As we've seen above, the command echo just repeats any subsequent text.

Now enter

echo ~

Why did this happen?

The next part of the practical will make use of a file that you will need to download. First, make sure you are in your Project_0 sub-directory.

cd ./Project_0

Get the file by running the following command.

wget ftp://ftp.ensembl.org/pub/release-89/fasta/drosophila_melanogaster/ncrna/Drosophila_melanogaster.BDGP6.ncrna.fa.gz

So far, the only output we have seen has been in the terminal (stdout).

We can redirect the output of a command to a file instead of to standard output using the greater than symbol (>), which we can almost envisage as an arrow.

As a simple example we can write text to a file.

Using the command echo prints text to stdout

echo "Hello there"

However, we can 'capture' this text and redirect it to a file using the > symbol.

echo "Hello there" > hello.txt

Notice that the text no longer appeared in your terminal!

This is because we sent it to the file hello.txt.

To look at the contents of hello.txt use either one of the commands less, cat or head.

Once you've looked at it, delete it using the command rm to make sure you keep your folder nice and tidy, as well as free from unimportant files.

Another alternative is to use the >> symbol, which only creates a blank file if one doesn't exist.

If one with that name already exists, this symbol doesn't create an empty file first, but instead adds the data from stdout to the end of the existing data within that file.

echo -e '# Sequence identifiers for all ncrna in dm6' > SeqIDs.txt

In this command, we've created a header for the file, and we can now add the information we need after this using the >> symbol.

This trick of writing a header at the start of a file is very common and can be used to add important information to a file.

Now let's add another row describing where we've obtained the data from.

echo -e '# Obtained from ftp://ftp.ensembl.org/pub/release-89/fasta/drosophila_melanogaster/ncrna/Drosophila_melanogaster.BDGP6.ncrna.fa.gz on 2022-03-04' >> SeqIDs.txt

Have a look at the file using less

less SeqIDs.txt

Now we can add the sequence identifiers, but first you need to gunzip the compressed file.

gunzip drosophila_melanogaster/ncrna/Drosophila_melanogaster.BDGP6.ncrna.fa.gz

grep -e '^>' Drosophila_melanogaster.BDGP6.ncrna.fa >> SeqIDs.txt

(You can look up grep with the man command and find what the -e option does.)

Inspect this once again using less, head or cat

Sometimes we need to build up our series of commands and send the results of one to another.

The pipe symbol (|) is the way we do this and it can literally be taken as placing the output from one command into a pipe and redirecting it somewhere new.

This is where thinking about the output of a command as a data stream can be very helpful.

As a simple example, we could take the output from an ls command and send it to the pager less.

ls -lh /usr/bin | less

Page through the output until you get bored, then hit q to quit.

This process can also be visualised using the following diagram from Unix Bootcamp:

As you may have realised, these file types don't play well with MS Word, Excel and the like. We need different ways to look through these and as we go, hopefully you'll get the hang of this. First we'll download the file GCF_000182855.2_ASM18285v1_genomic.gff for Lactobacillus amylovorus from the NCBI database.

wget ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/all/GCF/000/182/855/GCF_000182855.2_ASM18285v1/GCF_000182855.2_ASM18285v1_genomic.gff.gz

gunzip GCF_000182855.2_ASM18285v1_genomic.gff.gz

This file is in gff format, which is very commonly used.

The first 9 lines of this file is what we refer to as a header, which contains important information about how the file was generated in a standardised format.

Many file formats have these structures at the beginning, but for our purposes today we don't need to use any of this information so we can move on.

Have a look at the beginning of the file just to see what it looks like.

head -n12 GCF_000182855.2_ASM18285v1_genomic.gff

Notice the header lines begin with one or two hash symbols, whilst the remainder of the file contains information about the genomic features in tab-separated format. As there is a lot of information about each feature, note that each line after the header will probably wrap onto a second line in the terminal. The first feature is annotated as a region in the third field, whilst the second feature is annotated as a gene.

{:.no_toc}

- How many features are contained in this file?

- If we tried the following:

wc -l GCF_000182855.2_ASM18285v1_genomic.gffwould it be correct?

This will give 4529, but we know the first 9 lines are header lines. To count the non-header lines you could try several things:

grep -vc '^#' GCF_000182855.2_ASM18285v1_genomic.gff

or

grep -c '^[^#]' GCF_000182855.2_ASM18285v1_genomic.gff

Make sure you understand both of the above commands as it may not be immediately obvious!

As mentioned above, this file contains multiple features such as regions, genes, CDSs, exons or tRNAs. If we wanted to find how many regions are annotated in this file we could use the processes we've learned above:

grep -c 'region' GCF_000182855.2_ASM18285v1_genomic.gff

If we wanted to count how many genes are annotated, the first idea we might have would be to do something similar using a search for the pattern 'gene'.

{:.no_toc}

Do you think this is the number of regions and genes?

- Try using the above commands without the

-cto inspect the results. - Try searching for the number of coding DNA sequences using the same approach (i.e. CDS) and then add the two numbers?

- Is this more than the total number of features we found earlier?

- Can you think of a way around this using regular expressions?

Some of the occurrences of the word gene or region appear in lines which are not genes or regions. We could restrict the search to one of the tab-separated fields by including a white-space character in the search. The command:

grep -e '\sgene\s' GCF_000182855.2_ASM18285v1_genomic.gff | wc -l

will give a different result again as now we are searching for the word gene surrounded by white-space.

Note that we've also used the pipe here to count results using the wc command.

We could have also used grep -e with the -c flag set.

Alternatively, there is a command cut available.

Call the manual page (man cut) and inspect the option -f.

man cut

We can simply extract the 3rd field of this tab-delimited file by using the f3 option.

cut -f3 GCF_000182855.2_ASM18285v1_genomic.gff | head -n12

(You can ignore any errors about a Broken pipe.)

However, this hasn't cut the third field from the header rows as they are not tab-delimited.

To remove these we need to add one further option.

Call up the man page and look at the -s option.

This might seem a bit confusing, but this means don't print lines without delimiters which would be the comment lines in this file.

cut -f3 -s GCF_000182855.2_ASM18285v1_genomic.gff | head

Now we could use our grep -E approach and we know we're counting the correct field.

cut -f3 -s GCF_000182855.2_ASM18285v1_genomic.gff | grep -Ec 'gene'

A similar question would be: How many types of features are in this file?

The commands cut, along with sort and uniq may prove to be useful when answering this

cut -f3 -s GCF_000182855.2_ASM18285v1_genomic.gff | sort | uniq -c

In the above some of the advantages of the pipe symbol can clearly be seen. Note that we haven't edited the file on disk, we've just streamed the data contained in the file into various commands.

One additional and very useful command in the terminal is sed, which is short for stream editor. A tutorial is available at http://www.grymoire.com/Unix/Sed.html.

Instead of the man page for sed the info sed page is larger but a little easier to digest.

This is a very powerful command which can be a little overwhelming at first.

If using this for your own scripts and you can't figure something out, remember 'Google is your friend' and sites like \url{www.stackoverflow.com} are full of people wrestling with similar problems to you.

These are great places to start looking for help and even advanced programmers use these tools.

For today, there are two key sed functionalities that we want to introduce.

- Using

sedto alter the contents of a file/input; - Using

sedto print regions of a file

The command sed can be used to replicate the functionality of the head and grep commands, but with a little more power at your fingertips.

By default sed will print the entire input stream it receives, but setting the option -n will turn this off.

This is useful if we wish to restrict our output to a subset of lines within a file, and by including a p at the end of the script section, only the section matching the results of the script will be printed.

Make sure you are in the Practical_0 directory and we can look through the file Drosophila_melanogaster.BDGP6.ncrna.fa again.

sed -n '1,10 p' Drosophila_melanogaster.BDGP6.ncrna.fa

This will print the first 10 lines, like the head command will by default.

However, we could now print any range of lines we choose.

Try this by changing the script to something interesting like 101,112 p.

We could also restrict the range to specific lines by using the sed increment operator ~.

sed -n '1~4p' Drosophila_melanogaster.BDGP6.ncrna.fa

This will print every 4th line, beginning at the first, and is very useful for files with multi-line entries.

The fastq file format from NGS data, and which we'll look at next week will use this format.

We can also make sed operate like grep by making it only print the lines which match a pattern.

sed -En '/TGCAGGCTC.+(GA){2}.+/ p' Drosophila_melanogaster.BDGP6.ncrna.fa

Note however, that the line numbers are not present in this output, and the pattern highlighting from grep is not present either.

For regular expression pattern matching with grep or sed here is quick summary table of special characters and their meaning.

| Special Character | Meaning |

|---|---|

| \w | match any letter or digit, i.e. a word character |

| \s | match any white space character, includes spaces, tabs & end-of-line marks |

| \d | match any digit from 0 to 9 |

| . | matches any single character |

| + | matches one or more of the preceding character (or pattern) |

| * | matches zero or more of the preceding character (or pattern) |

| ? | matches zero or one of the preceding character (or pattern) |

| {x} or {x,y} | matches x or between x and y instances of the preceding character |

| ^ | matches the beginning of a line (when not inside square brackets) |

| $ | matches the end of a line |

| () | contents of the parentheses treated as a single pattern |

| [] | matches only the characters inside the brackets |

| [^] | matches anything other than the characters in the brackets |

| | | either the string before or the string after the "pipe" (use parentheses) |

| \ | don't treat the following character in the way you normally would. This is why the first three entries in this table started with a backslash, as this gives them their "special" properties. In contrast, placing a backslash before a . symbol will enable it to function as an actual dot/full-stop. |

Now we've had a look at many of the key tools, we'll move on to writing scripts which is one of the most common things a bioinformatician will do. We often do this on a HPC to run long data processing pipelines (or workflows).

Scripts are commonly written to perform repetitive tasks on multiple files, or need to perform complex series of tasks and writing the set of instructions as a script is a very powerful way of performing these tasks. They are also an excellent way of ensuring the commands you have used in your research are retained for future reference. Keeping copies of all electronic processes to ensure reproducibility is a very important component of any research. Writing scripts requires an understanding of several key concepts which form the foundation of much computer programming, so let's walk our way through a few of them.

Two of the most widely used techniques in programming are that of the for loop, and logical tests using an if statement.

A for loop is what we use to cycle through an input one item at a time

for i in 1 2 3; do (echo "$i^2 = $(($i*$i))"); done

In the above code the fragment before the semi-colon asked the program to cycle through the values 1, 2 and 3, letting the variable i take each value in order of appearance.

- Firstly: i = 1, then i = 2 and finally i = 3.

- After that was the instruction on what to do for each value where we multiplied it by itself

$(($i*$i))to give i². We placed this as the text string ("$i^2 = $(($i*$i))") for anechocommand to return.

Note that the value of the variable i was prefaced by the dollar sign ($).

This is how the bash shell knows it is a variable, not the letter i.

The command done then finished the do command.

All commands like do, if or case have completing statements, which respectively are done, fi and esac.

An important concept which was glossed over in the previous paragraph is that of a variable.

These are just labels for a slot which can have a value that may change.

In the above loop, the same operation was performed on the variable i, but the value changed from 1 to 2 to 3.

Variables in shell scripts can hold numbers or text strings and don't have to be formally defined as in some other languages.

We will commonly use this technique to list files in a directory, then to loop through a series of operations on each file.

If statements are those which only have a binary yes or no response.

For example, we could specify things like:

- if (

i>1) thendosomething, or - if (

fileName == bob.txt) thendosomething else

Notice that in the second if statement, there was a double equals sign (==).

This is the means compare the first argument with the second argument.

This differs from a single equals sign which is commonly used to assign the first argument to be what is given in the second argument.

This use of double operators is very common, notably you will see && to represent the command and, and || to represent or.

A final useful trick to be aware of is the use of an exclamation mark to reverse a command.

A good example of this is the use of the command != as the representation of not equal to in a logical test.

Now that we've been through just some of the concepts and tools we can use when writing scripts, it's time to tackle one of our own where we can bring it all together.

Every bash shell script begins with what is known as a shebang, which we would commonly recognise as a hash sign followed by an exclamation mark, i.e \#!.

This is immediately followed by /bin/bash, which tells the interpreter to run the command bash in the directory /bin.

This opening sequence is vital and tells the computer how to respond to all of the following commands.

As a string this looks like:

#!/bin/bash

The hash symbol generally functions as a comment character in scripts. Sometimes we can include lines in a script to remind ourselves what we're trying to do, and we can preface these with the hash to ensure the interpreter doesn't try to run them. It's presence as a comment here, followed by the exclamation mark, is specifically looked for by the interpreter but beyond this specific occurrence, comment lines are generally ignored by scripts and programs.

Let's now look at some simple scripts. These are really just examples of some useful things you can do and may not really be the best scripts from a technical perspective. Hopefully they give you some pointers so you can get going

Don't try to enter these commands directly in the terminal!!! They are designed to be placed in a script which we will do after we've inspected the contents of the script (see next page). First, let's just have a look through the script and make sure we understand what the script is doing.

#!/bin/bash

# First we'll declare some variables with some text strings

ME='Put your name here'

MESSAGE='This is your first script'

# Now well place these variables into a command to get some output

echo -e "Hello ${ME}\n${MESSAGE}\nWell Done!"

- You may notice some lines that begin with the # character. These are comments which have no impact on the execution of the script, but are written so you can understand what you were thinking when you wrote it. If you look at your code 6 months from now, there is a very strong chance that you won't recall exactly what you were thinking, so these comments can be a good place just to explain something to the future version of yourself. There is a school of thought which says that you write code primarily for humans to read, not for the computer to understand.

- Another coding style which can be helpful is the enclosing of each variable name in curly braces every time the value is called, e.g.

${ME}Whilst not being strictly required, this can make it easy for you to follow in the future when you're looking back. - Variables have also been named using strictly upper-case letters. This is another optional coding style, but can also make things clear for you as you look back through your work. Most command line tools use strictly lower-case names, so this is another reason the upper-case variable names can be helpful.

{:.no_toc} In the above script, there are two variables. Although we have initially set them to be one value, they are still variables. What are their names?

{:.no_toc}

Let's create an empty file which will become our script.

We'll give it the suffix .sh as that is the common convention for bash scripts.

Make sure you're in the Practical_0 folder, then enter:

touch wellDone.sh

Now open this using the using the text editor nano:

nano wellDone.sh

Enter the above code into this file setting your actual name as the ME variable, and save it by using Ctrl+o (indicated as ^O) in the nano screen.

Once you're finished, you can exit the nano editor by hitting Ctrl+x (written as ^X).

Assuming that you've entered everything correctly, we can now execute this script by simply entering

bash wellDone.sh

Unfortunately, this script cannot be executed without calling bash explicitly but we can also enable execution of the file directly by setting the execute flag in the file permissions.

First let's look at what permissions we have:

ls -lh *.sh

You should see output similar to this:

-rw-rw-r-- 1 a1234567 a1234567 0 Mar 2 20:39 welldone.sh

- Note how the first entry is a dash (

-) indicating this is a file. - Next come the three Read/Write/Execute triplets which are

rw-followed byrw-andr--

{:.no_toc}

Interpret the final triplet? What are these permissions indicating, and for whom?

As you can see, the x flag has not been set in any of the triplets, so this file is not executable as a script yet.

To do this, we simply need to set the x flag, then we'll look again using long-listing format.

chmod +x wellDone.sh

ls -lh *.sh

Note how the file now has the x flag set for every user, which means every user can execute this script.

Now we can execute the script by calling it using the file path.

One of the settings in bash though won't allow you to execute the file from the same folder, so we need to add the ./ prefix to the script.

./wellDone.sh

We can set each of these flags for all triplets using + to turn the flag on, or - to turn the flag off.

If we wanted to remove write permissions for all users we could simply use the command:

chmod -w wellDone.sh

ls -lh *.sh

This can be a very useful trick for write-protecting files!

These flags actually represent binary bits that are either on or off. Reading from right to left:

- the first bit is the execute flag, which has value 1

- the second bit is the write flag, which has the value 2

- the third bit is the read flag, which has the value 4

Thus each combination of flags can be represented by a single integer, as shown in the following table:

| Value | Binary | Flags | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 000 |

--- |

No read, no write, no execute |

| 1 | 001 |

--x |

No read, no write, execute |

| 2 | 010 |

-w- |

No read, write, no execute |

| 3 | 011 |

-wx |

No read, write, execute |

| 4 | 100 |

r-- |

Read, no write, no execute |

| 5 | 101 |

r-x |

Read, no write, execute |

| 6 | 110 |

rw- |

Read, write, no execute |

| 7 | 111 |

rwx |

Read, write, execute |

We can now set permissions using a 3-digit code, where 1) the first digit represents the file owner, 2) the second digit represents the group permissions and 3) the third digit represents all remaining users.

To set the permissions for our script to read-write-executefor you and any other users in the group you belong to, we could now use

chmod 774 wellDone.sh

ls -lh *sh

{:.no_toc} What will the final 4 in the above settings do?

In the initial script we used two variables ${ME} and ${MESSAGE}.

Now let's change the variable ${ME} in the script to read as ME=$1.

First we'll create a copy of the script to edit, and then we'll edit using nano

cp wellDone.sh wellDone2.sh

nano wellDone2.sh

We may need to set the execute permissions again.

chmod +x wellDone2.sh

ls -lh *sh

This time we have set the script to receive input from stdin (i.e. the keyboard), and we will need to supply a value, which will then be placed in the variable ${ME}.

Choose whichever random name you want (or just use "Boris" as in the example) and enter the following

./wellDone2.sh Boris

As you can imagine, this style of scripting can be useful for iterating over multiple objects. A trivial example, which builds on a now familiar concept would be to try the following.

for n in Boris Fred; do (./wellDone2.sh ${n}); done

As a good example, this script could summarise key features in a file.

Then we could simply pass the script multiple files using this strategy, and write the output to another file using the > symbol.

Here's an example of a script which uses a for loop.

#!/bin/bash

FILES=$(ls)

COUNT=0

for f in ${FILES};

do

((COUNT++))

ln=$(wc -l ${f} | sed -E 's/([0-9]*).+/\1/g')

echo "File number ${COUNT} (${f}) has ${ln} lines"

done

Save this as a script in the Practical_0 folder called lineCount.sh.

Add comments where you think you need them to make sure you understand what's happening.

{:.no_toc}