A microservice written in node.js for enabling static, server-less applications to log in using GitHub. Unlike existing alternatives, it works for as many different client IDs as you'd like. This lets you run a single microservice that knows all your client secrets rather than one for each app or service.

In order to let users log into our application with GitHub, we can use the GitHub OAuth system for web apps. For this we register our app with GitHub.com and they give us a Client ID and Client Secret. The ID is public, the secret is supposed to be... wait for it... a secret!

I like to build clientside JS apps as completely static files. Which means we don't have a server somewhere, where we can keep and use that client secret. We don't just want to put it in our static JS, because... well, then it's no longer secret.

If you read the GitHub OAuth Docs you notice that at step #2, we have to make a POST request to GitHub that includes the secret. So what do we do?

To solve this, we can run a little simple server (perhaps on a small free/cheap Heroku server) that does just that part: It knows your secret.

But additionally, it's common to register an app for each environment you need to test in. So, for a single app you may actually register two or three apps with github. One while developing locally, one for staging, one for production each with their own ID and secret and now, its own secret-keeping service.

To deal with this, and to embrace the whole microservices idea, we could instead create a single service that knows about all client IDs and secrets. That's what this is. Then, whenver we want to add another app, we just add a config item in heroku (or whever) and restart the service.

It's intended to be a simple, consistent, minimalist JSON API that lets you pass a client ID and "code" as per GitHub docs,

- Provides a single CORS-enabled endpoint you can hit with AJAX that makes the GitHub request, including the secret, and returns the result.

- Written in node.js using hapi

- descriptive, consistent JSON responses with proper status codes

- all but successful requests will have

4xxstatus codes and JSON responses are generated with boom for predictable structure.

- Your client IDs are simply environment variables whose value is the corresponding client secret (this plays nicely with services like Heroku)

- You make an ajax request that looks as follows (using jquery for brevity):

$.getJSON('https://secret-keeper.yourdomain.com/YOUR_CLIENT_ID/YOUR_CODE')

.done(function (data) {

console.log('data', data)

})

.fail(function (data) {

console.log('failed', data)

})

})So, the URL should be as follows:

https://yourhost.com/{ YOUR CLIENT ID }/{ YOUR CODE }

You can optionally also include state, redirect_uri, domain as a query paramaters.

?state={{ YOUR STATE PARAM }}&redirect_uri={{ YOUR REDIRECT URI }}

If included, state and redirect_uri simply get passed through to GitHub, domain is github.com by default but can be changed via query param make it possible to use this with GitHub Enterprise.

- Make sure you have a heroku account and are logged in.

- click this button:

and follow instructions

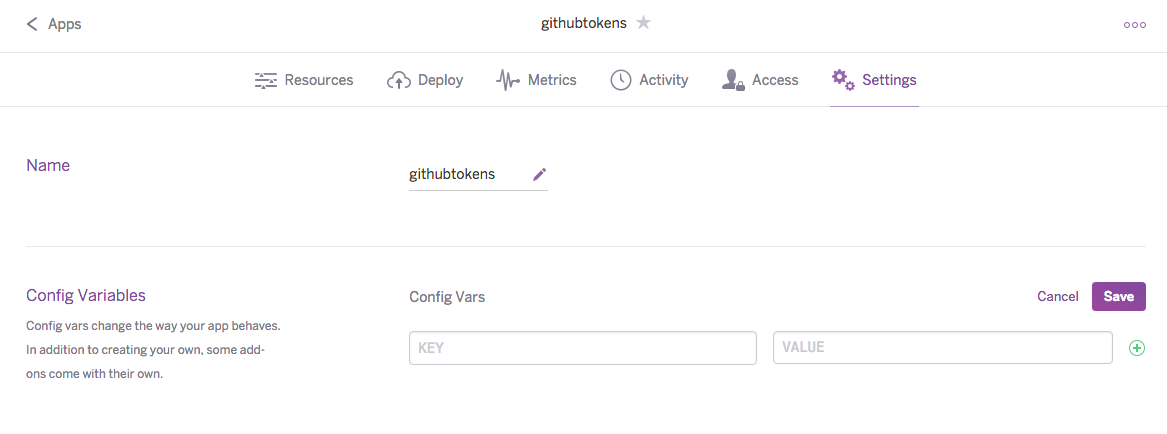

- Enter your client IDs/secrets as config variables in Heroku:

You can either set env variables in the command when you run the node server:

port=5000 YOUR_CLIENT_ID=CORRESPONDING_SECRET node server.js

Since that can be a bit messy you can also just put your client ID/secrets into env.json. Anything you put here will simply be added as environment variables.

{

"YOUR CLIENT ID": "YOUR CLIENT SECRET",

"YOUR OTHER CLIENT ID": "YOUR OTHER CLIENT SECRET"

}The only other thing that's configurable with environment variables is the PORT.

Created by @HenrikJoreteg. Inspired by gatekeeper.